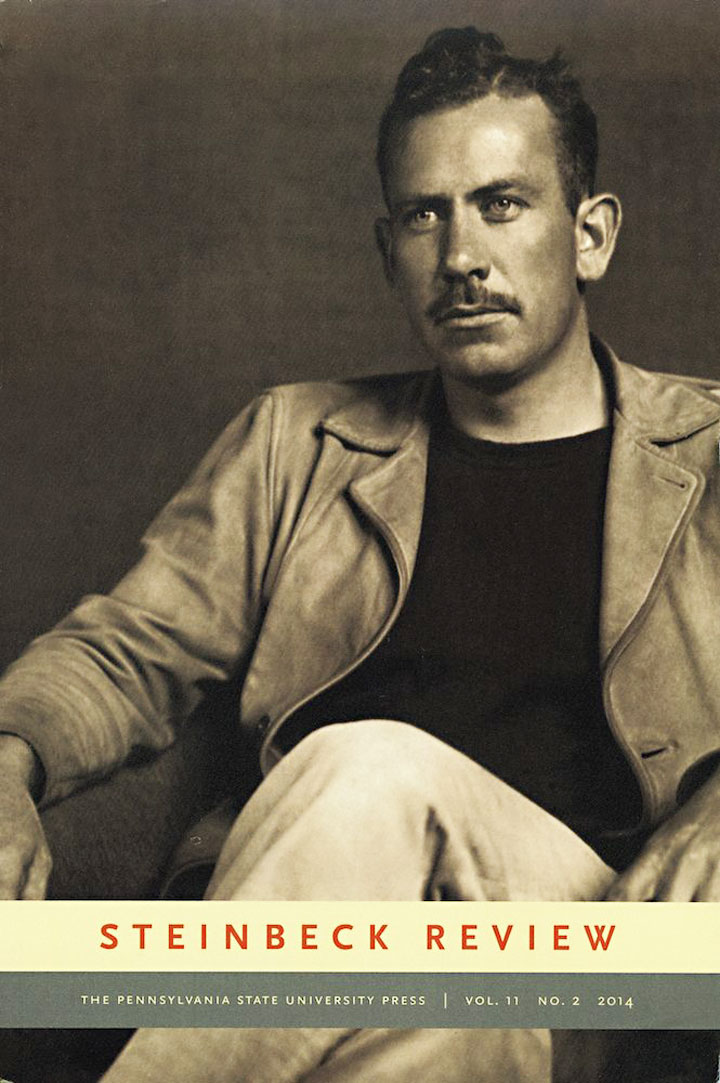

Mark your calendar for May 2016, but put on your thinking cap today. The newly renamed International Society of Steinbeck Scholars will host John Steinbeck as an International Writer, a conference on the author’s continued relevance for the 21st century, in San Jose, California, May 4-6, 2016. Scholars, students, and lovers of Steinbeck everywhere are invited to participate by attending and submitting a paper for presentation at this landmark event, hosted by the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University. According to the recent issue of Steinbeck Review—printed by Penn State Press, a powerhouse of scholarly journals on popular subjects such as John Steinbeck—the 2016 conference will probe Steinbeck’s connections with classical and modern literature, philosophy, politics, ethics, gender studies, and world affairs. Have global ideas about Steinbeck’s internationalism worth exploring in a paper of your own? Subscribe today and submit your proposal between August 2015 and March 2016.

Think Global, Act Now! 2016 John Steinbeck Conference at San Jose State University

Coming Soon! Marin County Stage-Adaptation Reading of Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle

Steinbeck lovers are invited to a reading of In Dubious Battle, John F. Levin’s stage adaptation of Steinbeck’s Great Depression labor-strike novel, at California’s Mill Valley Public Library on Tuesday, November 4. The free 7:00 p.m. event is sponsored by the library and the Playwrights’ Lab, the play-development program of the Throckmorton Theatre, a popular Marin County performing arts venue. Hal Gelb—the producing director of the Playwrights’ Lab and a frequent writer for The New York Times, The Nation, and Bay Area print and broadcast outlets—directs. John F. Levin, the author, is a San Francisco-based screenwriter and freelance journalist whose work has appeared in New West, Oui, and McCalls. Mill Valley, host of the Mill Valley Film Festival, is located in southern Marin County, immediately north of San Francisco via the Golden Gate Bridge.

Kite Runner Author Accepts 2014 John Steinbeck Award at San Jose State University

Khaled Hosseini, author of the bestselling 2003 novel The Kite Runner, will receive the John Steinbeck “In the Souls of the People” Award at San Jose State University on September 10, 2014. The 7:30 p.m. event benefits the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies.

An American physician, writer, and humanitarian, Khaled Hosseini was born in Afghanistan. Like The Kite Runner, his 2007 novel A Thousand Splendid Suns is set in part in his native country, which has experienced foreign invasion, civil war, and occupation by violent forces since he was born in its capital, Kabul, in 1965. His father, a moderate Moslem, served as an Afghan diplomat in Iran and later in Paris before seeking political asylum in the United States with his wife, a teacher, and their children.

Khaled Hosseini, the eldest of five, finished high school in San Jose, California, before graduating from Santa Clara University and receiving his M.D. from the University of California, San Diego. He completed his medical residency at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and continued to practice medicine for more than a year after the publication of The Kite Runner. His third novel, And the Mountains Echoed, was published in 2013.

The Khaled Hosseini Foundation, a 501(c)(3) charitable organization, provides direct assistance and economic support to elements of the Afghan population most affected by poverty and violence—refugees, women, and children. A multi-ethnic country with ancient roots stretching from China to South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East, Afghanistan combines beauty, tragedy, and civility that provide the rich texture and colorful context of Khaled Hosseini’s heartfelt fiction.

The critically acclaimed film version of The Kite Runner was nominated for Academy and Golden Globe awards in 2008 and received a Christopher Award and a Critics Choice Award from the Broadcast Film Critics Association the same year. The name of the John Steinbeck Award comes from Chapter 25 of The Grapes of Wrath, an earlier novel that combined anger and love and also achieved greatness as a movie: “In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.”

Nick Taylor—author of Father Junipero’s Confessor, teacher of creative writing at San Jose State University, and director of the Steinbeck Studies Center—makes the connection with John Steinbeck’s masterpiece while noting that Khaled Hosseini is the first writer who is primarily a novelist to receive the annual award since it was established in 1996:

Nick Taylor—author of Father Junipero’s Confessor, teacher of creative writing at San Jose State University, and director of the Steinbeck Studies Center—makes the connection with John Steinbeck’s masterpiece while noting that Khaled Hosseini is the first writer who is primarily a novelist to receive the annual award since it was established in 1996:

Plenty of novelists know how to tell a good story, and plenty try to raise consciousness through their work, but very few do both. Steinbeck used fiction to call attention to the plight of migrant farmworkers, in particular the “Okies” of the 1930s, a group that many Americans had heard of, but did not know much about. Khaled Hosseini’s work does this for people of Afghanistan, a population most Americans know only from the news.

The last winner of the John Steinbeck Award was the filmmaker Ken Burns. Previous awardees include filmmakers Michael Moore and John Sayles; musicians Bruce Springsteen, Jackson Browne, Joan Baez, and John Mellencamp; labor leader and civil rights activist Dolores Huerta; actor Sean Penn; broadcast journalist Rachel Maddow; and three writers—Arthur Miller, Studs Terkel, and Garrison Keillor.

Lisa Vollendorf, dean of San Jose State University’s College of Humanities and the Arts, is actively involved with the Steinbeck Studies Center, which is named for Martha Heasley Cox, Professor Emerita of English at San Jose State University. Known for her warm style, energetic pace, and attention to detail, Dean Vollendorf—whose field is Romance languages—recently helped organize an international conference in Portugal. In her comments for this post she put the 2014 John Steinbeck Award event into local and global perspective:

Lisa Vollendorf, dean of San Jose State University’s College of Humanities and the Arts, is actively involved with the Steinbeck Studies Center, which is named for Martha Heasley Cox, Professor Emerita of English at San Jose State University. Known for her warm style, energetic pace, and attention to detail, Dean Vollendorf—whose field is Romance languages—recently helped organize an international conference in Portugal. In her comments for this post she put the 2014 John Steinbeck Award event into local and global perspective:

This fall we celebrate Khaled Hosseini, a globally important author who immigrated to the Bay Area at the age of fifteen. Hosseini credits his teacher, Jan Sanchez, with giving him a copy of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, an encounter that inspired him to write fiction in English. Hosseini’s artistic achievements are extraordinary; many credit him with single-handedly humanizing modern Afghanistan for American audiences. His humanitarian work has helped create economic opportunities and meet basic shelter needs for refugees, women, and children in Afghanistan. Khaled Hosseini’s artistic sensibilities and humanitarian work make him a perfect recipient of the Steinbeck Award. We are grateful he accepted and we are all looking forward to the ceremony.

Khaled Hosseini expressed appreciation for John Steinbeck and enthusiasm about receiving the John Steinbeck Award in a statement to reporters earlier this month:

I am greatly honored to be given an award named after John Steinbeck, not only an icon of American literature but an unrelenting advocate for social justice who so richly gave voice to the poor and disenfranchised. Both as a person and a writer, I count myself among the millions on whose social consciousness Steinbeck has made such an indelible impact.

Tickets to the award ceremony can be purchased in person at the San Jose State University Event Center or online at Eventbrite.

Portrait photo of Khaled Hosseini by Patrick Tehan courtesy of the San Jose Mercury News.

The Grapes of Wrath in Organ Music at John Steinbeck’s Episcopal Church: Event Update

John Steinbeck’s childhood Episcopal church in Salinas, California, will celebrate the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath on August 22, 2014, in a concert of organ music inspired by the music-loving author’s life and work. James Welch, California’s leading concert organist, will perform Franklin D. Ashdown’s recently commissioned Steinbeck Suite, as well as organ music by composers who Steinbeck especially admired or who were living and working in California during the writer’s time.

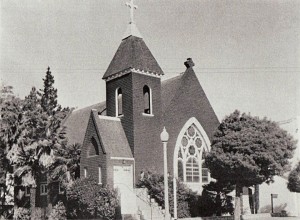

The 7:00 p.m. program on August 22—originally planned for Carmel Mission—will take place at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, located since 1954 at 1071 Pajaro Street in the Salinas, California, suburb of Monterey Park. The original St. Paul’s Episcopal Church attended by John Steinbeck (shown at left) was located near the Steinbeck family home on Salinas, California’s historic Central Avenue. (The El Camino Real Diocese of the Episcopal Church, currently headquartered in the Monterey area, plans to move to a large Victorian structure near the Steinbeck House on Central Avenue within the next few weeks.)

The 7:00 p.m. program on August 22—originally planned for Carmel Mission—will take place at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, located since 1954 at 1071 Pajaro Street in the Salinas, California, suburb of Monterey Park. The original St. Paul’s Episcopal Church attended by John Steinbeck (shown at left) was located near the Steinbeck family home on Salinas, California’s historic Central Avenue. (The El Camino Real Diocese of the Episcopal Church, currently headquartered in the Monterey area, plans to move to a large Victorian structure near the Steinbeck House on Central Avenue within the next few weeks.)

John Steinbeck remained active at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church until he left for college in 1919. He was christened by the church’s rector in 1905 and confirmed by a visiting bishop in 1916, and he served as an altar boy, sang in the junior choir, and participated in Boy Scout meetings in the church basement as a teenager. In this photograph he is shown leaving the church, hymnal in hand, behind a young crucifer named “Skunkfoot” Hill on Easter Sunday in 1914. Hill’s name, as well as that of Bishop Nichols of the Episcopal Church in California, appear in The Winter of Our Discontent in an episode based, in part, on John Steinbeck’s childhood. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church plays a less positive role in East of Eden, where Aron’s mother Cathy slips into the back pew to observe her son, a callow convert to the Episcopal Church who is ignorant of the fact that his mother—believed to be dead—runs a Salinas, California, whorehouse.

John Steinbeck remained active at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church until he left for college in 1919. He was christened by the church’s rector in 1905 and confirmed by a visiting bishop in 1916, and he served as an altar boy, sang in the junior choir, and participated in Boy Scout meetings in the church basement as a teenager. In this photograph he is shown leaving the church, hymnal in hand, behind a young crucifer named “Skunkfoot” Hill on Easter Sunday in 1914. Hill’s name, as well as that of Bishop Nichols of the Episcopal Church in California, appear in The Winter of Our Discontent in an episode based, in part, on John Steinbeck’s childhood. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church plays a less positive role in East of Eden, where Aron’s mother Cathy slips into the back pew to observe her son, a callow convert to the Episcopal Church who is ignorant of the fact that his mother—believed to be dead—runs a Salinas, California, whorehouse.

The program created by Welch (shown here) will open with organ music by J.S. Bach, the composer John Steinbeck described in Sea of Cortez as “breaking through” to a state of mystical sublimity in sound. It will continue with the Salinas, California, premiere of Ashdown’s Steinbeck Suite, a five-movement work written in honor of the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath and inspired by scenes from Tortilla Flat and The Grapes of Wrath. Ashdown is one of America’s most widely published composers of church organ music.

The program created by Welch (shown here) will open with organ music by J.S. Bach, the composer John Steinbeck described in Sea of Cortez as “breaking through” to a state of mystical sublimity in sound. It will continue with the Salinas, California, premiere of Ashdown’s Steinbeck Suite, a five-movement work written in honor of the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath and inspired by scenes from Tortilla Flat and The Grapes of Wrath. Ashdown is one of America’s most widely published composers of church organ music.

Also featured on the August 22 program will be a pair of mid-century California composers who were inspired by the Monterey Peninsula landscape and affiliated with Episcopal churches in San Francisco: Richard Purvis, the organist of Grace Cathedral following World War II, and Dale Wood, the organist at the Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin in the 1970s. It is conceivable that John Steinbeck, who enjoyed hearing organ music and visiting San Francisco, heard Purvis play. Wood’s distinctive organ music style was influenced by musical sources familiar to Steinbeck, including gospel tunes of the type heard in The Grapes of Wrath and incorporated by Ashdown into the lively fourth movement of Steinbeck Suite.

John Steinbeck’s appreciation for Episcopal church ceremony and organ music is evident throughout his writing, nowhere more obviously than in the famous Easter Sunday chapter from Sea of Cortez. Welch’s program will conclude with Wood’s brilliant setting of the chorale “That Easter Day With Joy Was Bright” in recognition of this seminal passage from John Steinbeck’s most philosophical work.

Suggested donation for the August 22 concert is $15 at the door.

Celebrating Steinbeck in Sound at Carmel Mission

The 75th anniversary of the publication of The Grapes of Wrath will be celebrated in a public organ concert beginning at 7:00 p.m. on August 22 at California’s Carmel mission. Inspired by The Grapes of Wrath, Tortilla Flat, Sea of Cortez, and John Steinbeck’s admiration for the music of J.S. Bach, the literary-minded program will be performed by James Welch, California’s foremost concert organist and a fan of John Steinbeck’s fiction.

The historic Carmel mission is located at 3080 Rio Road in Carmel-by-the-Sea, several miles south of Monterey and Pacific Grove. Along with inland Salinas, the three Monterey County communities were inhabited or frequented by Steinbeck during his formative California period and appear frequently in his writing. The 1935 novel Tortilla Flat is set in Monterey, the site of Cannery Row and the launching point of Steinbeck’s 1940 Sea of Cortez expedition with his close friend Ed Ricketts, the marine biologist, to study the coastal ecology and culture of Baja California. The result of their legendary trip and writing collaboration was Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research (1941), the book that distilled the ideas animating The Grapes of Wrath, In Dubious Battle, and Of Mice and Men, Steinbeck’s labor trilogy of the late 1930s.

A native of Southern California who started college as a pre-med student, James Welch earned a doctorate in organ performance from Stanford University and lives in Palo Alto, where he has held the post of organist at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church since 1993. A member of the music department at Santa Clara University and a former faculty member at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he has researched and recorded Latin American organ music on a Fulbright grant, performed music by European and American masters at cathedrals and concert halls throughout the world, and recorded works by a variety of composers for the organ, including the four featured on his August 22 concert at Carmel Mission. (Welch will perform a program of music by British composers on the famed organ of the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City on August 3.)

Music for Steinbeck from J.S. Bach to “Night in Monterey”

Welch’s Carmel mission concert will open with J.S. Bach’s mighty Toccata in C major and other selections by the composer whom Steinbeck and Ricketts described in Sea of Cortez as “breaking through” to a state of mystical sublimity in sound. It will continue with Steinbeck Suite, a five-movement work written by Franklin D. Ashdown in honor of the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath and inspired by scenes from Tortilla Flat and from Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. Ashdown, who lives in New Mexico, is one of America’s most widely published living composers of music for organ and choir. Steinbeck Suite was premiered by Welch at the Santa Clara mission on February 17 and will be published in 2014 by Zimbel Press, a respected publisher of new music. Ashdown visited the Carmel mission following the Santa Clara premiere and played its pipe organ.

Also featured on Welch’s Carmel mission program will be a pair of 20th century California composers who were inspired by the Monterey Peninsula and San Francisco Bay Area in their musical writing. Richard Purvis (1913-1994), the organist and choirmaster of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco following World War II, enjoyed camping on the Monterey coast, a passion colorfully reflected in Nocturne (“Night in Monterey”), one of several Purvis pieces that will be performed by Welch, who published a biography of Purvis in 2013. Dale Wood (1934-2003), the organist and choirmaster at San Francisco’s Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin in the 1970s, wrote music with a distinctively California style influenced by musical forms familiar to Steinbeck, including jazz, gospel music, and the music J.S. Bach. Welch’s Carmel mission concert will include Wood’s brilliant setting of the chorale “That Easter Day With Joy Was Bright” in celebration of the seminal Easter Sunday chapter from Sea of Cortez.

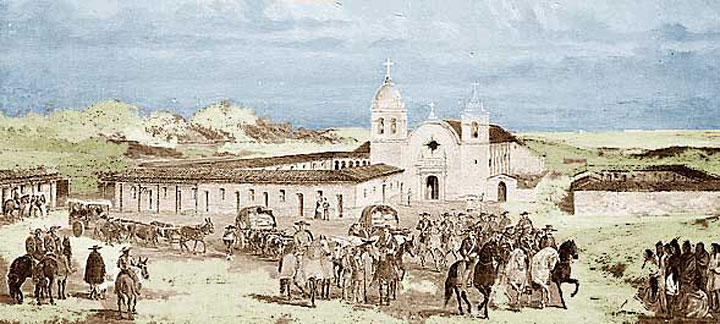

Carmel Mission and Steinbeck’s Feeling for Catholicism

San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission was the second California mission built under the administration of Junipero Serra, the Franciscan missionary who made the Carmel mission his headquarters from 1770 until his death in 1784. Like other California missions, it fell into disuse and decay following secularization by the Mexican government in the 19th century. By Steinbeck and Ricketts’s time, the restoration advocated by Steinbeck and others was underway, and the Carmel mission became a parish church in 1932—the original goal of the Franciscans for the missions they built along the “King’s Highway” between San Diego and Sonoma under Spanish colonial rule. Its beauty, acoustics, and location have made it a popular concert venue and tourist destination today. The Carmel mission was named a minor basilica by Pope John XXIII in 1960 and hosted a visit by Pope John Paul II during his 1987 North American tour.

Ashdown’s choral work, Missa Brevis de Requiem, is dedicated to the memory of both popes, and his Franciscan Pastorale, based on St. Francis of Assisi’s “All Creatures of Our God and King,” is among his most frequently performed works for the organ. It is tempting to imagine that John Steinbeck, who was friendly to Catholicism in his fiction and familiar with the legend and lore of St. Francis and the California missions built by the Franciscans, would be pleased.

Academic Stars Illuminate The Grapes of Wrath

On May 3 experts from the University of Virginia, San Jose State University, and Claremont Graduate University enlightened 350 attendees of the 34th Steinbeck Festival—held at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California—about The Grapes of Wrath. As different in style as The Grapes of Wrath is from Gone With the Wind, each of the speakers—Susan Shillinglaw, a professor of English at San Jose State University; Stephen Railton, Professor of American Literature and Digital Humanities at the University of Virginia; Rick Wartzman, the executive director of the Drucker Institute at Claremont Graduate University—aligned Steinbeck’s masterpiece with matters of abiding importance, illuminating aspects of an enduring novel that still shocks and surprises.

On May 3 experts from the University of Virginia, San Jose State University, and Claremont Graduate University enlightened 350 attendees of the 34th Steinbeck Festival—held at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California—about The Grapes of Wrath. As different in style as The Grapes of Wrath is from Gone With the Wind, each of the speakers—Susan Shillinglaw, a professor of English at San Jose State University; Stephen Railton, Professor of American Literature and Digital Humanities at the University of Virginia; Rick Wartzman, the executive director of the Drucker Institute at Claremont Graduate University—aligned Steinbeck’s masterpiece with matters of abiding importance, illuminating aspects of an enduring novel that still shocks and surprises.

San Jose State University’s Susan Shillinglaw on Teaching

The author of two books in one year—John and Carol Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage and On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath”—Susan Shillinglaw has taught, written, and organized around Steinbeck at San Jose University for 25 years. So familiar with her subject that she can speak flawlessly without notes, the San Jose State University President’s Scholar and National Steinbeck Center Scholar-in-Residence traced the roots of The Grapes of Wrath back to rural Oklahoma, the home of a real-life migrant family named Joat, and connected it to the contemporary concept of one-world ecology, first explored by Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts in the 1930s.

Susan Shillinglaw has taught, written, and organized around Steinbeck at San Jose University for 25 years.

Shillinglaw’s deft description of the four levels of meaning in Steinbeck’s novel unified by this concept seemed perfectly designed to make the long book easier to embrace for classroom teachers, a significant percentage of her audience. The San Jose State University veteran explained why reading long books is still important for students with an apt analogy from personal experience. Earlier in the week, she said, she had attended the stage version of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men in New York. She noted that Hilton Als, the New Yorker magazine drama critic, panned the production for depending on celebrity casting to draw young viewers to an old play.

Shillinglaw’s deft description of the four levels of meaning in Steinbeck’s novel seemed perfectly designed to make the long book easier to embrace for classroom teachers.

Shillinglaw stated that it was the first time she ever saw a New York audience stand and clap so quickly at the end of a show. If it takes a James Franco to get youngsters to attend live theater, she wondered, what’s the harm? They were there, they were moved, and they loved what they saw. If it takes a teacher’s prodding to induce kids to read The Grapes of Wrath, that’s worth the time and effort, too, she added. Although her students at San Jose State University “self-select” by enrolling in her Steinbeck course, she noted that frequent quizzes are necessary to keep them on track, particularly with long books like The Grapes of Wrath.

The University of Virginia’s Stephen Railton on Reading

Like me, Susan Shillinglaw attended graduate school at the University of Virginia’s rival, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Noting that at one time the Department of English was the University of Virginia’s largest department, she provided a smooth transition for the speaker who came next, the University of Virginia English professor Stephen Railton. Shillinglaw’s focus on Steinbeck is singular: her knowledge of the writer’s life is encyclopedic, and her observations about his work are splendidly spontaneous. Railton’s style is more structured and his scope more synoptic, placing Steinbeck in the broader context of American literary history. Unlike Shillinglaw, Railton delivered his remarks from a prepared script, but that didn’t slow him down. Could it be that he speaks so brilliantly in public because he comes from the University of Virginia, an institution founded by Thomas Jefferson, the U.S. President who wrote effortlessly but had to work hard to project his voice?

Railton’s style is more structured and his scope more synoptic, placing Steinbeck in the broader context of American literary history.

In Chapel Hill we complained that the University of Virginia seemed set on cornering the American literature market. Railton’s presentation suggested that our concern was justified. The editor of works by and about Cooper, Emerson, Whitman, and Twain, Railton has developed digital libraries of Twain, Faulkner, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of the other great protest novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. As amply demonstrated in his comments about The Grapes of Wrath, this makes Railton a kind of humanities engineer, a new and interesting breed on campus. He certainly knows where the connecting lines lie under the surface of American writing from 19th century Transcendentalism to Naturalism and Modernism, mapping the convergence of these movements in John Steinbeck with ease and connecting The Grapes of Wrath with equal precision to Uncle Tom’s Cabin and to The Wasteland. Consider the relationship of three “Tom’s,” he suggested: Stowe’s Uncle Tom, Steinbeck’s Tom Joad, and the Wasteland poet from St. Louis, Thomas Stearns Eliot.

A thought that profound is a paper in itself, but Railton moved right on, connecting Steinbeck to other writers in ways equally ingenious. For example, he noted that the author of the “sentimental” novel The Grapes of Wrath was at heart a literary modernist who heeded Ezra Pound’s call to “make it new” in his writing. But Steinbeck differed fundamentally from Pound, Eliot, and Faulkner, modern writers whose dislike of sentiment created “a kind of gated community of aesthetics” in their work. Unlike his more detached contemporaries, Steinbeck was emotionally engaged, writing “not out of curiosity but impatience, even anger” and creating in Tom Joad “an existential member of the Lost Generation.” Steinbeck also differed from Naturalists such as Dreiser, Norris, and Crane, students of social Darwinism who wrote about individuals victimized by power in the shadow of the Panic of 1893. The author of The Grapes of Wrath was a meliorist who believed in the possibility of progress. Writing in the deeper shadow of the Great Depression, Steinbeck felt that the natural order for humanity was “evolutionary change, not just unremitting struggle.”

The author of The Grapes of Wrath was a meliorist who believed in the possibility of progress.

So satisfying an insight offers a tempting place to stop, but Railton also looked closely at Steinbeck’s text, observing that The Grapes of Wrath opens on a wasteland, like Eliot’s poem, and that the journey of Tom Joad parallels that of Stowe’s Uncle Tom. Rose of Sharon loses her baby and her brother never becomes an uncle, but unlike Stowe’s protagonist—whose hope is for Heaven—Joad’s breakthrough is post-Christian, an updated version of Emerson’s Over-Soul in which all people participate. Tom learns this religion from the ex-preacher Casy, but unlike Casy, Tom fights back rather than forgiving, “a warrior convert” to the new gospel of social justice. The Grapes of Wrath, Railton concluded, is John Steinbeck’s “Newer Testament.” As if in benediction, the University of Virginia professor sang Casy’s “Yessir, that’s my Savior” to the tune Steinbeck had in mind: “Yessir, that’s my baby.” Like Thomas Jefferson, the self-described “aging hippie” from the University of Virginia has an educated ear.

Claremont Graduate University’s Rick Wartzman on the Burning and Banning of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath

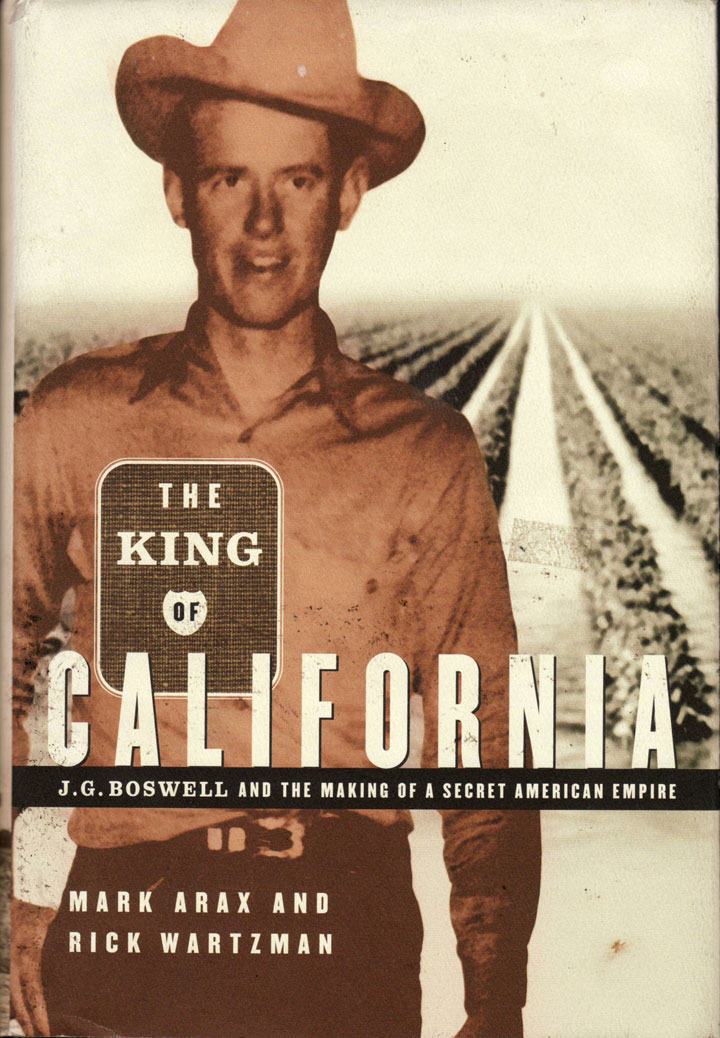

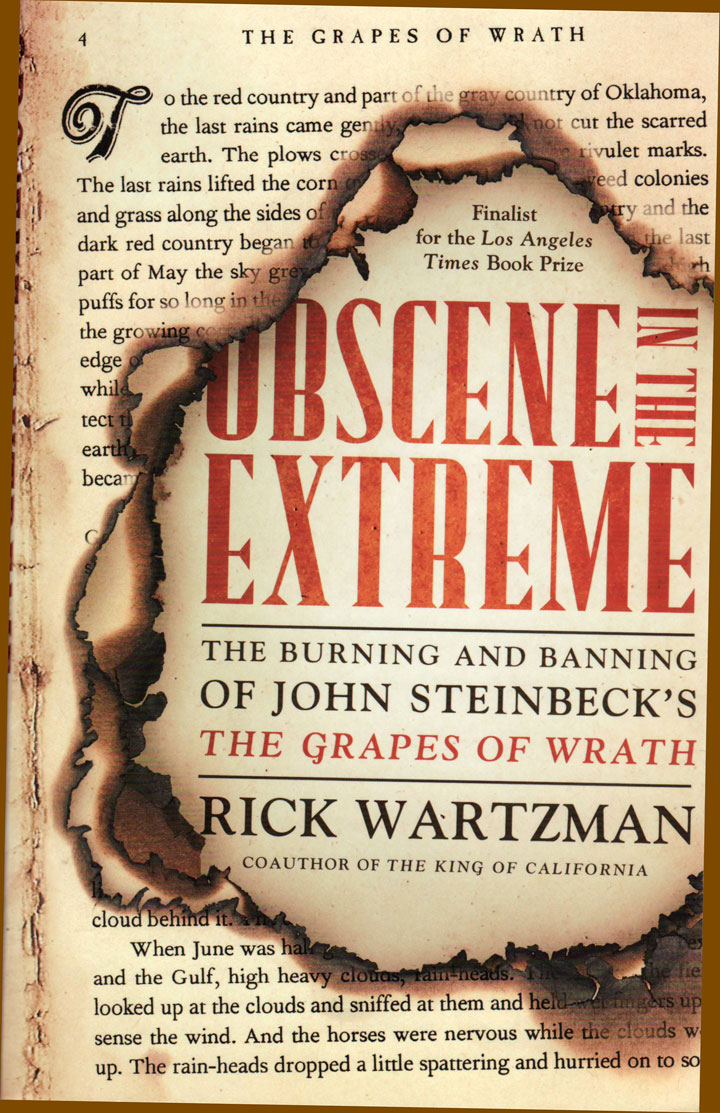

Susan Shillinglaw extemporized without notes. Stephen Railton performed from a script. Rick Wartzman, the third speaker of the day, projected images from his laptop. It was an appropriate medium for the executive director of Claremont Graduate University’s Drucker Institute—described by Time.com as “a social enterprise whose mission is strengthening organizations to strengthen society.” A former writer and editor at The Wall Street Journal and Los Angeles Times, Wartzman is the author of award-winning investigations of political power in California—The King of California: J.G. Boswell and the Making of a Secret American Empire (with Mark Arax) and Obscene in the Extreme: The Burning and Banning of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Each of these books explores an archetypal conflict: the price in individual liberty paid to oligarchic greed, the story at the heart of Steinbeck’s masterpiece. Shillinglaw and Railton illuminated the novel’s narrative, context, and connections. Wartzman detailed its aftermath.

Shillinglaw and Railton illuminated the novel’s narrative, context, and connections. Wartzman detailed its aftermath.

Prior to The Grapes of Wrath, a pair of California writer-activists admired by Steinbeck—Jack London and Sinclair Lewis—published prescient novels about a future United States under fascism. George Orwell cited the influence of London’s book on the writing of 1984, the British bestseller that continues to rival The Grapes of Wrath in global popularity. Neither of the earlier novels—London’s The Iron Heel (1902), Lewis’s It Can Happen Here (1935)—is read much anymore, but Steinbeck would have been familiar with both. If he voted in the general election of 1934, he likely voted for the writer-activist Upton Sinclair, the Democratic candidate for Governor of California. A celebrity socialist with popular appeal, Sinclair was defeated by the well-funded campaign of disinformation waged by California’s corporate elite—including Wartzman’s former employer, the Los Angeles Times. Frank Merriam, the establishment candidate, won the Governor’s seat.

Sinclair’s populist policies prevailed four years later, when Culbert Olson beat Merriam to become California’s first Democratic Governor since 1895. As Wartzman observed, the state’s corporate interests were understandably alarmed. A Mormon atheist from Utah, Olson had campaigned for Sinclair in 1934 and supported President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Remarkably, Olson refused to say “so help me God” when his oath of office was administered by a California Supreme Court Justice with the name William Waste. Olson dared to challenge the influence of the Catholic Church in California’s system of public education, provoking the wrath of John Cantwell, the archbishop of Los Angeles, and Archbishop John Mitty of San Francisco. Virtually alone among elected officials in the country’s most geographically exposed state, Olson opposed the internment of Japanese-Americans following Pearl Harbor. In 1942 he lost to the Republican Earl Warren, future Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Olson opposed the internment of Japanese-Americans following Pearl Harbor. In 1942 he lost to the Republican Earl Warren, future Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

When Olson took office on January 2, 1939, California’s power structure shook, setting the stage for the burning and banning of The Grapes of Wrath. Wartzman’s narrative of events between April and August 1939 was dramatic. During that turbulent time, Carey McWilliams—a Los Angeles writer-activist allied with Sinclair and employed by Olson—published Factories in the Field, a survey of migrant worker conditions in California caused by the rapacity of the state’s corporate landowners. McWilliams’ dry statistics vindicated Steinbeck’s angry book, blunting the impact of counter-Grapes of Wrath efforts by writers such as Ruth Comfort Mitchell, Steinbeck’s summer neighbor in genteel Los Gatos.

McWilliams’ dry statistics vindicated Steinbeck’s angry book, blunting the impact of counter-Grapes of Wrath efforts by writers such as Ruth Comfort Mitchell, Steinbeck’s summer neighbor in genteel Los Gatos.

Mitchell may not have been related to the Georgia author of the same name who wrote Gone With the Wind, the 1936 bestseller that became an award-winning film the year The Grapes of Wrath was published. But in the context of Stephen Railton’s remarks, Margaret Mitchell’s pro-Confederacy fantasy can be read as a work of delayed anti-Uncle Tom’s Cabin fiction; Wartzman noted that two-dozen anti-Uncle Tom books appeared during Harriet Beecher Stowe’s lifetime. Ruth Comfort Mitchell’s Of Human Kindness, a polite work written to counter the perceived obscenity of The Grapes of Wrath, was quickly forgotten. Gone With the Wind remains second only to the Bible in continuing U.S. sales, far ahead of The Grapes of Wrath, its spiritual opposite.

Who burned The Grapes of Wrath when it first appeared? In Bakersfield, California, Clell Pruett—a man who hadn’t read the book—posed for the camera as he lit the match. Pruett’s employer was Bill Camp, head of the anti-labor, anti-Grapes of Wrath Associated Farmers organization in Kern County; Camp enlisted Pruett for the photo-op to prove that real farm workers didn’t appreciate how Steinbeck had portrayed them. Following Pearl Harbor, Pruett left California and returned to Missouri to mine lead. That is where Rick Wartzman interviewed Pruett not long before he died. Pruett still hadn’t read The Grapes of Wrath but promised Wartzman that he would. When he did, he told Wartzman that reading hadn’t changed his mind.

In Bakersfield, California, Clell Pruett—a man who hadn’t read the book—posed for the camera as he lit the match.

Pruett’s feelings about The Grapes of Wrath were shared by people in Steinbeck’s hometown, where a 1936 strike by lettuce-packers was suppressed and The Grapes of Wrath was later burned. Like Jack London and Sinclair Lewis, John Steinbeck feared fascism in America and thought he recognized its signs in California. A dramatic instance involved Salinas and the violent reaction of the town’s citizens to the 1936 lettuce strike. Steinbeck’s response was L’Affaire Lettuceburg, a vigorous denunciation of local power brokers in short-fiction form. The piece was so scathing that Steinbeck—on the advice of his wife and in the interest of his safety—retracted the manuscript and refused to let it be published, proactively burning his own book. As I sat in the National Steinbeck Center audience listening to the stellar speakers who had come to Salinas from San Jose State University, the University of Virginia, and Claremont Graduate University, I pondered the remark about John Steinbeck made by the town’s former mayor in his morning introduction: “He used us in life; we use him in death.”

John Steinbeck’s Signature Festival in Salinas, California

When the National Steinbeck Center presents the 34th Steinbeck Festival on May 2-4, the annual celebration will honor the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath. But as readers of John Steinbeck are aware, what went before is as important as the now in any story. This is part of the story behind the John Steinbeck festival begun in the writer’s hometown in 1980.

When the National Steinbeck Center presents the 34th Steinbeck Festival on May 2-4, the annual celebration will honor the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath. But as readers of John Steinbeck are aware, what went before is as important as the now in any story. This is part of the story behind the John Steinbeck festival begun in the writer’s hometown in 1980.

A Festival for John Steinbeck in the Writer’s Hometown

The first Steinbeck Festival was held in Salinas, California, a small city with a significant agricultural industry, in June of 1980. Labeled a literary festival by its founders—John Gross, the Salinas, California librarian, and David Aguilar, a teacher at Hartnell College—the modest event was cosponsored by the library and the college, a community college with a reputation for civic outreach. Along with artifacts from John Steinbeck’s life, there were films, lectures, panel discussions, and a stage play. Some participants got college credit for attending, but the three-day event was open to anyone. Best yet, it was free—bus tours included. People in Salinas, California came together to honor a celebrated son, and the annual Steinbeck Festival was on its way.

The first Steinbeck Festival was held in Salinas, California, a small city with a significant agricultural industry, in June of 1980.

The 1981 festival was even bigger than the first. A 13-day event featuring 23 speakers, 10 films, seven stage performances, seven bus tours, and several ambitious exhibits, its keynote speaker was the award-winning actor Burgess Meredith, John Steinbeck’s longtime friend. The educational mission and academic connection remained strong, coordinated by Hartnell College and the Salinas, California library and advised by Jackson Benson, the San Diego State University professor who was writing John Steinbeck’s official biography.

The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, Arrives

Like Hartnell College, San Diego State is a public school with community spirit, and the festival’s academic ties attracted government support. Funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the 1982 festival moved to the first weekend in August, with public readings from John Steinbeck’s books, a pair of well-attended panel discussions, 18 lectures, 15 film showings, and four tours. As in 1980 and 1981, the 1982 festival was free.

Like Hartnell College, San Diego State is a public school with community spirit, and the festival’s academic ties attracted government support. Funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the 1982 festival moved to the first weekend in August, with public readings from John Steinbeck’s books, a pair of well-attended panel discussions, 18 lectures, 15 film showings, and four tours. As in 1980 and 1981, the 1982 festival was free.

The fourth festival included the first book publication event held anywhere to launch Jackson Benson’s definitive life of John Steinbeck.

It was also a prelude to 1983, when the fourth Steinbeck Festival opened with a premiere: the first publication event held anywhere to launch Benson’s The Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer, still the definitive life of John Steinbeck. Although college credit continued to be available and literature remained foremost, the new venue chosen for the festival—Salinas, California’s Community Center—reflected the dramatic growth in attendance and the increasing importance of local volunteers, including tour guides who received special training in advance.

From Russia to Hartnell College with Love—For Reading

The 1984 festival went global. Although centered in Salinas, California, it was augmented by the presence of the Second International Steinbeck Congress, bringing together authorities on John Steinbeck from throughout the world. Among the 34 featured speakers were scholars from India, Japan, and Korea; other events included 10 bus tours, 16 films, and four plays. Among the funders was the California Council for the Humanities—like the National Endowment for the Arts grant, an enviable “good housekeeping seal of approval” for a community event begun and staffed by volunteers.

The 1984 festival went global. Although centered in Salinas, California, it was augmented by the presence of the Second International Steinbeck Congress, bringing together authorities on John Steinbeck from throughout the world. Among the 34 featured speakers were scholars from India, Japan, and Korea; other events included 10 bus tours, 16 films, and four plays. Among the funders was the California Council for the Humanities—like the National Endowment for the Arts grant, an enviable “good housekeeping seal of approval” for a community event begun and staffed by volunteers.

John Steinbeck’s hopes for international cooperation were coming to fruition in Salinas, California.

Until recently, the annual festival continued to occur during the first week in August, running 4-5 days and attracting a variety of Steinbeck scholars, fans, and visitors to Salinas, California. Bus tours and films remained popular. But 1989 was a really big year. The 50th anniversary of the publication of The Grapes of Wrath drew international attention and became the inevitable focus of the festival. Glasnost was in the air, and scholars from the Soviet Union even came. John Steinbeck’s hopes for international cooperation—expressed 40 years earlier in A Russian Journal—were coming to fruition in Salinas, California.

A Son and Spouse of John Steinbeck Participate in Person

The festival’s 50th-anniverary focus on The Grapes of Wrath set the pattern for the future, and festivals in the 1990s frequently highlighted single books, including East of Eden, The Red Pony, America and Americans, and Cannery Row. The annual event continued to take place the first weekend in August so that educators from across the country—a mainstay of the audience—could attend.

The festival’s 50th-anniverary focus on The Grapes of Wrath set the pattern for the future, and festivals in the 1990s frequently highlighted single books, including East of Eden, The Red Pony, America and Americans, and Cannery Row. The annual event continued to take place the first weekend in August so that educators from across the country—a mainstay of the audience—could attend.

When offered accommodations elsewhere, the writer’s widow insisted on staying in the same Salinas, California hotel where the festival’s speakers were lodged.

However, the speakers weren’t always academicians. John Steinbeck IV, the writer’s younger son, was among the notable speakers with a personal connection. Elaine Steinbeck, John Steinbeck’s third wife, also attended one year. When offered accommodations elsewhere, the writer’s widow insisted on staying in the same Salinas, California hotel where the festival’s speakers were lodged.

National Steinbeck Center Calls Salinas, California Home

More and more volunteers were needed to make the annual event successful, and eventually it seemed that everyone got involved. If you lived in Salinas, California, then you—or someone you knew—was already pitching in when the Steinbeck Festival celebrated its 15h anniversary in 1996. Banners were hung across Main Street. The water company used their Pitney Bowles machine to promote the festival on customer-billing envelopes. Local companies donated printing and other essential services. Festival posters showed up in storefront windows all over town.

More and more volunteers were needed to make the annual event successful, and eventually it seemed that everyone got involved. If you lived in Salinas, California, then you—or someone you knew—was already pitching in when the Steinbeck Festival celebrated its 15h anniversary in 1996. Banners were hung across Main Street. The water company used their Pitney Bowles machine to promote the festival on customer-billing envelopes. Local companies donated printing and other essential services. Festival posters showed up in storefront windows all over town.

By the time the National Steinbeck Center opened in downtown Salinas, California, and took over event management in 1998, the literary festival devoted to the city’s greatest celebrity and dedicated to public education was well-established, well-attended, and well-respected.

By the time the National Steinbeck Center opened in downtown Salinas, California, and took over event management in 1998, the literary festival devoted to the city’s greatest celebrity and dedicated to public education was well-established, well-attended, and well-respected.

Pre-festival activities this year included events in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. May 2-4 activities include bus tours to familiar places in Steinbeck’s fiction—the Hamilton Ranch near King City, the historic Spreckels site near Salinas, and Ed Ricketts’ lab in Monterey—plus a number of evening surprises.

But that’s where we began: the foreground of a story with a background in Salinas, California volunteerism, public spirit, and community pride.

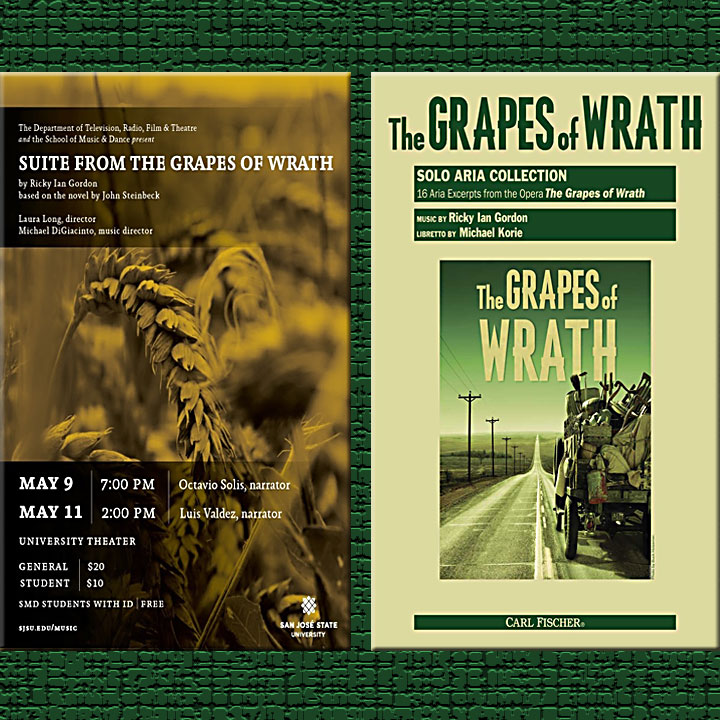

Hear Grapes of Wrath Opera at San Jose State University

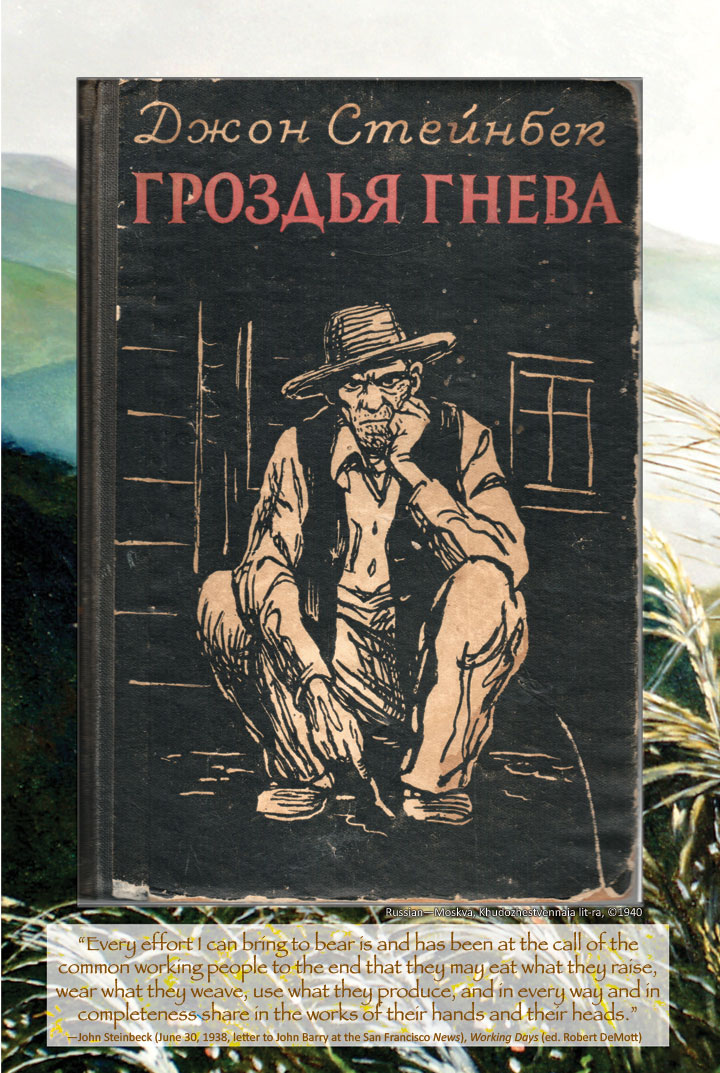

As interim director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, I have been particularly gratified by the university’s 75th anniversary celebration of The Grapes of Wrath. Ongoing events open to the public began with a colorful exhibition of book covers from foreign editions of The Grapes of Wrath, which has been translated into 45 languages since it was first published. As noted in my earlier post, the exhibition was created by Peter Van Coutren, the Steinbeck Studies Center’s archivist, and features little-known information about the novel’s history. (If you are visiting the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library on the San Jose State University campus this month, check out the exhibition on the fifth floor. It ends soon.)

As interim director of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, I have been particularly gratified by the university’s 75th anniversary celebration of The Grapes of Wrath. Ongoing events open to the public began with a colorful exhibition of book covers from foreign editions of The Grapes of Wrath, which has been translated into 45 languages since it was first published. As noted in my earlier post, the exhibition was created by Peter Van Coutren, the Steinbeck Studies Center’s archivist, and features little-known information about the novel’s history. (If you are visiting the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library on the San Jose State University campus this month, check out the exhibition on the fifth floor. It ends soon.)

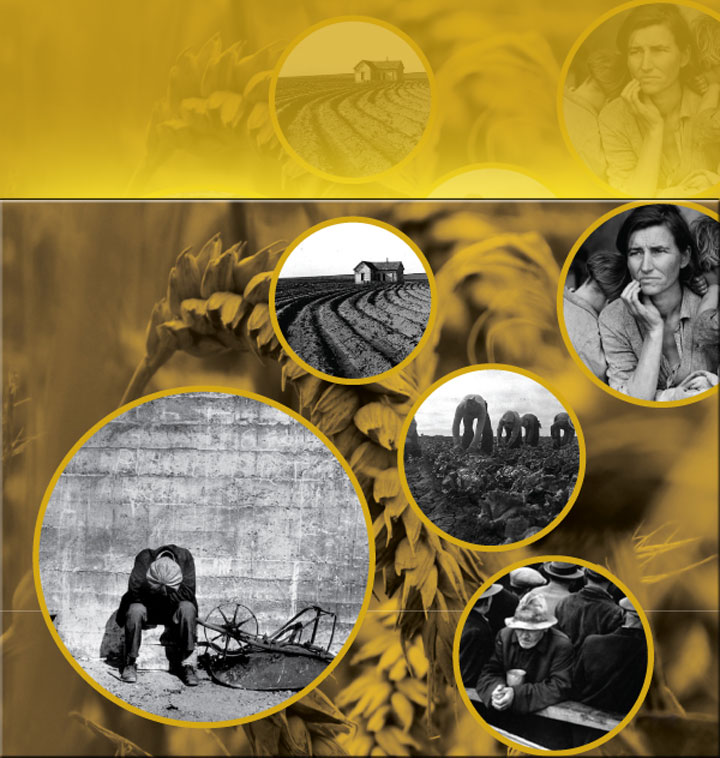

The Dust Bowl and Great Depression Take Center Stage

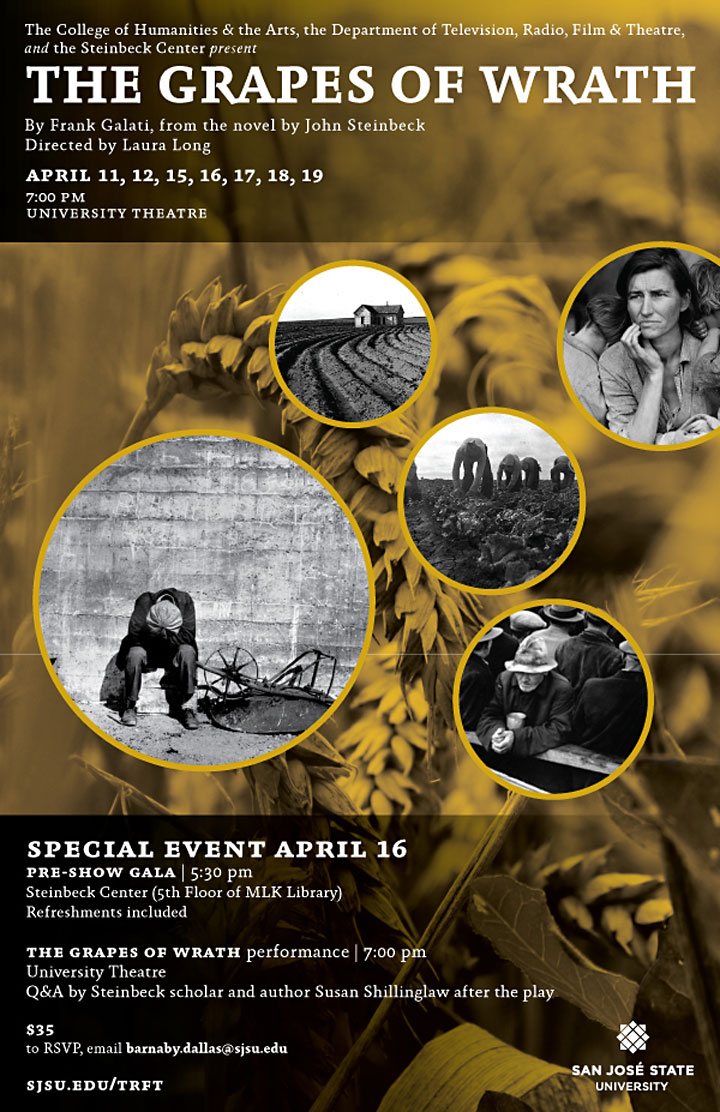

San Jose State University’s celebration of The Grapes of Wrath continued last month with a staging of Frank Galati’s award-winning 1989 dramatic adaptation by the Department of Television, Radio, Film, and Theatre Arts in collaboration with the Steinbeck Studies Center. The well-attended run of this play, directed by Laura Long and supported by Professors David Kahn and Barbaby Dalls, included a gala reception starring Susan Shillinglaw, the former director of the Steinbeck Studies Center, Professor of English and President’s Scholar at San Jose State University, and Scholar in Residence at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas. Shillinglaw’s new book On Reading “The Grapes of Wrath” was recently published by Penguin, and she signed copies for an enthusiastic crowd. Other San Jose State University faculty members led by Scot Guenter helped develop a Grapes of Wrath “readathon” sponsored by the SJSU Campus Reading Program—a 24-hour public reading of the entire book, also performed in April.

The Music of The Grapes of Wrath in Concert on Campus

When Viking Press published The Grapes of Wrath on April 14, 1939, John Steinbeck became both famous and infamous for his sympathetic portrayal of the Joads, a symbolic Dust Bowl migrant family from Oklahoma whose trials and tribulations in California made the author deeply unpopular with American Agribusiness. But the book won a Pulitzer Prize in 1940, and John Ford’s movie adaptation starring Henry Fonda is now part of our picture of life during the Great Depression. Steinbeck said that he wrote the novel with the structure of music in mind. Its operatic overtones inspired composer Ricky Ian Gordon and librettist Michael Korie to create a new opera based on the novel, first staged by the Minnesota Opera. The work will be performed in an unstaged concert version by San Jose State University’s music department on May 9 and 11. The speaking role of narrator will be filled by a pair of famous playwrights: Octavio Solis and Luis Valdez. A painting by Ron Clavier donated by the artist and inspired by the novel will be on display in the lobby.

Bravo! Ricky Ian Gordon and His Grapes of Wrath Opera

Ricky Ian Gordon (shown here) was born in 1956. Since its Minnesota premiere in 2007, his operatic treatment of The Grapes of Wrath has been performed in Salt Lake City, Pittsburgh, and Los Angeles, among other cities. Of the Los Angeles production, Los Angeles Times critic Mark Swed wrote that “the greatest glory of the opera is Gordon’s ability to musically flesh out the entire eleven-member Joad clan,” praising the composer for successfully merging Broadway musical theater with classical opera in the work. Writing in The New Yorker, Alex Ross compared it to “American popular music of the twenties and thirties: Gershwinesque song-and-dance numbers, a few sweetly soaring love songs in the manner of Jerome Kern, banjo-twanging ballads, saxed-up jazz choruses, even a barbershop quartet.” A two-act concert version of the opera directed by Eric Simonson and narrated by Jane Fonda was performed at Carnegie Hall in 2010. This version will be used for the San Jose State University production in a pair of performances beginning at 7:00 p.m. on May 9, and at 2:00 p.m. on May 11, both in the Hal Todd Theater on the San Jose State University campus. The musical production will also be directed by Laura Long.

San Jose State University Professor Sings Pittsburgh Role

The tenor Joseph Frank, director of the San Jose State University School of Music, sang the role of Grampa Joad for the Pittsburgh Opera’s production of Gordon’s Grapes of Wrath in 2008. The complete opera, recorded live by the Minnesota Opera, is available in a three-CD set with libretto liner notes on the PS Classics label. The vocal score and a selection of arias are available from Carl Fischer.

The tenor Joseph Frank, director of the San Jose State University School of Music, sang the role of Grampa Joad for the Pittsburgh Opera’s production of Gordon’s Grapes of Wrath in 2008. The complete opera, recorded live by the Minnesota Opera, is available in a three-CD set with libretto liner notes on the PS Classics label. The vocal score and a selection of arias are available from Carl Fischer.

Steppenwolf Theatre’s Grapes of Wrath Reprised at San Jose State University

San Jose State University continued its non-stop 75th anniversary party for The Grapes of Wrath in April with a revival of Frank Galati’s dramatization of John Steinbeck’s novel, praised by Chicago’s legendary writer Studs Terkel and premiered by Chicago’s award-winning Steppenwolf Theatre 25 years ago. Studs Terkel may be dead, but the progressive prophet’s ghost—like that of Tom Joad—haunts the heart of America in the age of Occupy Wall Street, Wal-Mart wages, and workers “tractored out [Studs Terkel’s words] by the cats.” In this context the San Jose State University production made a timeless work seem particularly timely.

San Jose State University continued its non-stop 75th anniversary party for The Grapes of Wrath in April with a revival of Frank Galati’s dramatization of John Steinbeck’s novel, praised by Chicago’s legendary writer Studs Terkel and premiered by Chicago’s award-winning Steppenwolf Theatre 25 years ago. Studs Terkel may be dead, but the progressive prophet’s ghost—like that of Tom Joad—haunts the heart of America in the age of Occupy Wall Street, Wal-Mart wages, and workers “tractored out [Studs Terkel’s words] by the cats.” In this context the San Jose State University production made a timeless work seem particularly timely.

We were in the audience for the April 16 performance at the San Jose State University theater and saw for ourselves why Galati’s play caught the attention of critics and won awards when it was first produced in Chicago, London, and New York. Despite the work’s ambitious scale, casting requirements, and technical demands, San Jose State University’s Department of Television, Radio, Film & Theatre was prepared for the task; the April run reprised a production by San Jose State University students and staff in the 1990s. Undaunted, director Laura Long and director of production Barnaby Dallas capitalized on the challenge of restaging Steinbeck’s 20th century story using 21st century actors from a distinctively diverse community.

We were in the audience for the April 16 performance at the San Jose State University theater and saw for ourselves why Galati’s play caught the attention of critics and won awards when it was first produced in Chicago, London, and New York. Despite the work’s ambitious scale, casting requirements, and technical demands, San Jose State University’s Department of Television, Radio, Film & Theatre was prepared for the task; the April run reprised a production by San Jose State University students and staff in the 1990s. Undaunted, director Laura Long and director of production Barnaby Dallas capitalized on the challenge of restaging Steinbeck’s 20th century story using 21st century actors from a distinctively diverse community.

Studs Terkel would have been pleased with the result of their imaginative rethinking. Long’s casting was unapologetically contemporary—multiracial, multigenerational, and a meaningful reminder that Steinbeck’s “Okies” are more than convenient stereotypes or skin-deep symbols of a bygone era. The production shots shown here courtesy of the San Jose State University theater department tell a story worth a thousand words—although Studs Terkel used fewer than 65 when we wrote this about the enduring relevance of The Grapes of Wrath during the period of Galati’s Steppewolf Theatre premiere, a time of deepening income inequality:

Studs Terkel would have been pleased with the result of their imaginative rethinking. Long’s casting was unapologetically contemporary—multiracial, multigenerational, and a meaningful reminder that Steinbeck’s “Okies” are more than convenient stereotypes or skin-deep symbols of a bygone era. The production shots shown here courtesy of the San Jose State University theater department tell a story worth a thousand words—although Studs Terkel used fewer than 65 when we wrote this about the enduring relevance of The Grapes of Wrath during the period of Galati’s Steppewolf Theatre premiere, a time of deepening income inequality:

It is 1988. We see the face on the six o’clock news. It could be a Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange shot, but that’s fifty years off. It was a face of despair, of an Iowa farmer, fourth generation, facing foreclosure. I’ve seen this face before. It is the face of Pa, Muley Graves, and all their lost neighbors, tractored out by the cats.

At San Jose State University, April’s John Steinbeck Month

This is the year of The Grapes of Wrath—its 75th anniversary—and the cause for self-reflection for readers of John Steinbeck, including me. My version is both personal and professional. I teach at San Jose State University, one of the world’s top centers of John Steinbeck research, and for the second time I am serving as interim director of the University’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies while Nicholas Taylor, the permanent director, is on leave.

This is the year of The Grapes of Wrath—its 75th anniversary—and the cause for self-reflection for readers of John Steinbeck, including me. My version is both personal and professional. I teach at San Jose State University, one of the world’s top centers of John Steinbeck research, and for the second time I am serving as interim director of the University’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies while Nicholas Taylor, the permanent director, is on leave.

John Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University

When I accepted the same post on a permanent basis in 2005, I was—to be frank—wet behind the ears, despite my apprenticeship 10 years earlier filling in for Susan Shillinglaw, the Steinbeck Studies Center director, during her sabbatical. I had a solid enough background teaching and writing about American Modernism, the era that includes John Steinbeck, although too often Steinbeck is ignored in academic discussion of his less popularly-read contemporaries such as Willa Cather, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, and T.S. Eliot. But I made some embarrassing errors anyway—like revealing my lack of familiarity with the 1950 stage production of Burning Bright, Steinbeck’s third, last, and least-successful experiment with the play-novella form following Of Mice and Men and The Moon Is Down.

Of course, I had huge shoes to fill when I became the permanent director in 2005. Susan Shillinglaw’s stature as a John Steinbeck scholar was enormous when she stepped down as director of the Center at San Jose State University, where she continues to teach, and it has continued to grow. Part of my learning curve in her footsteps was to deepen my knowledge of John Steinbeck’s life and work, particularly the agony and transcendence embodied in The Grapes of Wrath—a book that continues to create more heat than light for certain readers in Oklahoma and California, and the excuse for latter-day book-banning in places where controversial classics such as Huckleberry Finn are deemed morally unwise or politically incorrect.

Celebrating The Grapes of Wrath in Pictures and in Words

Celebrating The Grapes of Wrath in Pictures and in Words

When Viking Press published The Grapes of Wrath on April 14, 1939, John Steinbeck became a national celebrity. The following year his book won the Pulitzer Prize, John Ford made the movie starring Henry Fonda, and Steinbeck’s notoriety spread throughout a world already at war. To mark the 75th anniversary of the novel’s debut on the international stage this month, San Jose State University will sponsor a series of celebrations in honor of Steinbeck’s masterpiece—a work that is integral to California history, relevant to American society, and as well known as Huckleberry Finn to readers as far away as Russia and Japan.

As noted in an earlier post, an exhibition of colorful covers selected from foreign editions of The Grapes of Wrath is currently on display at the Center for Steinbeck Studies. The exhibit, assembled by Archivist Peter Van Coutren, is accompanied by information about the novel and its background. I recommend it to anyone visiting the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library on the San Jose State University campus.

Thanks to the efforts of San Jose State University faculty members such as Scot Guenter, the SJSU Campus Reading Program will sponsor a Grapes of Wrath “readathon”—a public performance of the entire novel, starting at 6:00 p.m. on April 16 and ending 24 hours later, more or less. Individuals who participate as readers will receive a gift, along with listing on the Spartans Care Read-a-thon Honor Roll. (In case you’re wondering, “Spartans” is the designation for San Jose State University’s sports teams.) Signing up is easy.

Reprising the Stage Version of Steinbeck’s Masterpiece

Reprising the Stage Version of Steinbeck’s Masterpiece

Thanks to the hard work of David Kahn, the chair of San Jose State University’s Department of TV, Radio, Film and Theater Arts, and his colleague Barnaby Dallas, the Coordinator of Productions, a main attraction will be the stage production of The Grapes of Wrath at the Hal Todd Theatre on the San Jose State University campus. The play—Frank Galati’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel—is directed by Laura Long and runs April 11-12 and April 15-19. The April 16 performance features a pre-performance reception and a post-play “talkback” with Susan Shillinglaw about her new book On Reading The Grapes of Wrath. Tickets can be purchased online.

Galati’s adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath premiered at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater in 1988 and ran for three years. It also traveled to London and New York, where it won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for best play of 1991. Galati received two 1990 Tony Awards—Best Play and Best Direction—for his work, which also garnered a half-dozen acting award nominations for cast members Gary Sinise, Terry Kinney, and Lois Smith. Galati, a former professor at Northwestern University, was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in 2004. San Jose State University produced his Grapes of Wrath in the 1990s, so this month’s run is a celebratory reprise.

In May there will be more—but I’ll save that for another time. Who said April was the cruelest month? At San Jose State University, it’s the coolest—thanks to John Steinbeck and The Grapes of Wrath.