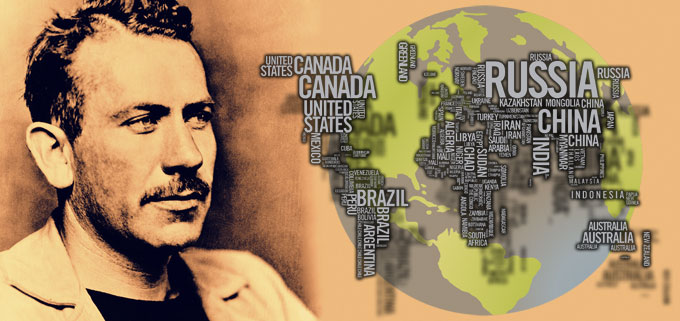

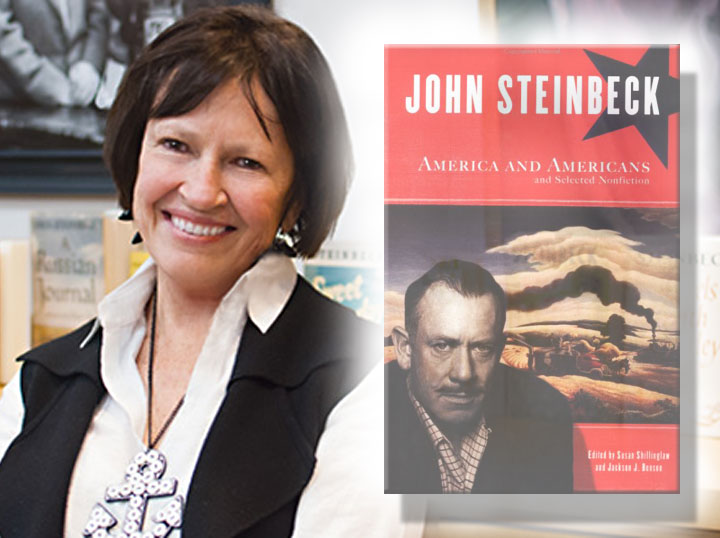

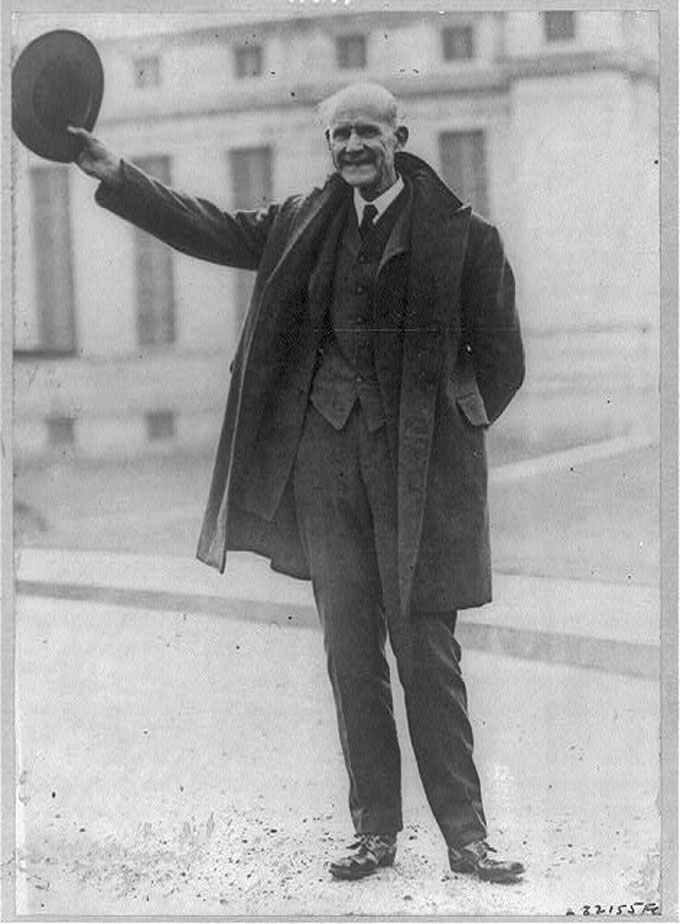

Though Eugene V. Debs is no longer a household name, John Steinbeck’s labor movement novels of the 1930s—In Dubious Battle and The Grapes of Wrath—were influenced by the words and witness of the progressive politician from Terre Haute, Indiana who ran for President in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920. Debs devoted his career to organizing the fight for better wages and working conditions; Steinbeck appropriated his statement of support for the mistreated, malnourished, and marginalized in society—“While there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free”—in the promise Tom Joad makes to his mother in The Grapes of Wrath. Debs uttered his statement in 1918, to the Cleveland, Ohio court that had convicted him of sedition for a speech he gave in Canton, Ohio protesting America’s entry into World War I—a war about which Steinbeck expressed misgivings 25 years later, in East of Eden. Despite repeated defeats during their lifetimes, Debs and Steinbeck remained optimistic about the future of humankind. In his 1962 Nobel acceptance speech, Steinbeck captured Debs’s faith in the possibility—and necessity—of human progress: “I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man, has no dedication nor any membership in literature.”

Eugene V. Debs died in Illinois in 1926, but his memory lives on in the work of the Eugene V. Debs Foundation, located in Terre Haute, Indiana, the city where Debs was born. The not-for-profit organization operates the Eugene V. Debs museum and gives an award each year in Debs’s name to recognize the contributions of outstanding individuals to the cause, much like the John Steinbeck humanitarian award given by the Steinbeck Studies Center in San Jose, California. The 2015 Debs award was made to James Boland, president of the International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers, at a banquet in Terre Haute on October 14. Pete Seeger, the labor movement troubadour honored by the John Steinbeck center in 2009, received the Eugene V. Debs award in 1979.

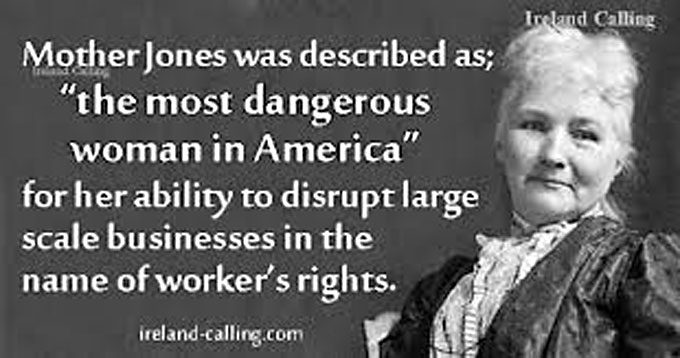

My family and I have been attending Debs award dinners almost that long, and I was pleased to see the Mother Jones Museum represented at this year’s banquet. Mary Harris Jones—a labor movement activist and community organizer in the same era as Eugene V. Debs—was an Irish immigrant, like James Boland and John Steinbeck’s grandparents, Samuel and Eliza Hamilton. Jones was called “the most dangerous woman in America” by critics; like Debs and Steinbeck, she had many, and she was an avid defender of immigrant and worker rights, like Debs and Steinbeck. There is probably no better parallel in modern American literature to the contemporary situation of undocumented workers in the U.S. than Steinbeck’s “Okie” migrants in The Grapes of Wrath. Mother Jones Magazine, a progressive publication, is headquartered in San Francisco, the center of the California labor movement in Steinbeck’s time and the backdrop for Steinbeck’s strike novel, In Dubious Battle.

Since the year the Debs award was given to Pete Seeger, almost every Debs dinner has featured a musician of note on the program. This year’s singer was Dana Lyons, a folk and alternative rock musician from Bellingham, Washington. Many of Dana’s songs concern the environment, but he is most famous for “Cows with Guns,” a hilarious song about another serious subject. John Steinbeck would have appreciated Dana’s sense of humor, as well as the environmental message delivered in the beautiful new music video, “The Great Salish Sea,” which can be viewed at Dana’s website. It sounds the alarm about the effects ship noise and fossil fuels have on the whales of the Salish Sea region in Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia—a region John Steinbeck and his friend Ed Ricketts, early ecologists, knew well.

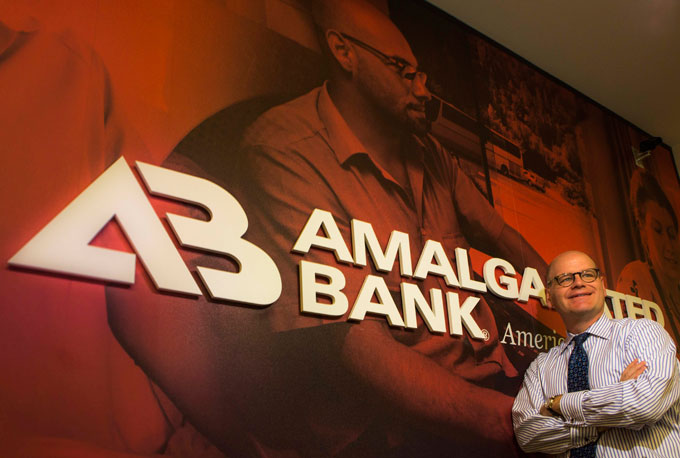

Another Debs dinner tradition is to have the annual award presented by a prominent proponent of progressive politics. This year’s presentation speaker was Keith Mestrich, president and CEO of Amalgamated Bank, the union-owned bank where Occupy Wall Street kept its funds. Founded in 1923 by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, the bank practices what Eugene V. Debs preached. Recently it raised the minimum wage it pays its employees to $15 an hour, and it is currently funding an ad campaign on New York subways supporting “ The Fight for $15.” When metro officials pulled the bank’s posters from subway cars because the message was too political, Amalgamated ran an ad on the front cover of the free subway paper, and Amalgamated volunteers began collecting signatures for the #RaiseTheWage petition the bank plans to send Congress.

In his remarks, Jim Boland (shown here speaking on TV) cited the influence of progressive writers on his political education, recalling how he felt as a young Irish immigrant to the United States to learn about Eugene V. Debs, the man he called “the ultimate American socialist.” Boland’s father and grandfather were union railroad workers, like Debs and my Irish grandfather, a political activist and socialist. During his speech, Jim cited two writers—John Dos Passos, John Steinbeck’s American contemporary, and James Connolly, the Irish socialist and patriot who was wounded in the 1916 Easter Uprising, then executed for his role in the Irish revolt against British rule. Before returning to Ireland from the United States in 1910 to fight for Irish independence, Connolly was a member of the International Workers of the World (IWW), the union that Debs helped found and that Steinbeck wrote about in the 1930s.

Unlike James Connolly and Eugene V. Debs, John Steinbeck was never jailed because of his politics. But people do die for their convictions in his novels—Casy in The Grapes of Wrath; the young strike organizer, also named Jim, in Steinbeck’s labor movement novel In Dubious Battle. Unlike Steinbeck, Debs is rarely mentioned in American classrooms today. In fact, the contribution of the entire labor movement to the making of American society is barely touched on in most high school history classes. The corporate media treat labor unions and leaders with suspicion, and politicians love to campaign against both, even in states like Indiana with strong labor movement roots. In Terre Haute, the Eugene V. Debs Foundation is working to counter this negative trend. Visitors are welcome at the Eugene V. Debs Museum, which is located on the campus of Indiana State University in Terre Haute. Tips on traveling to Terre Haute and visiting the museum are available on my travel blog.