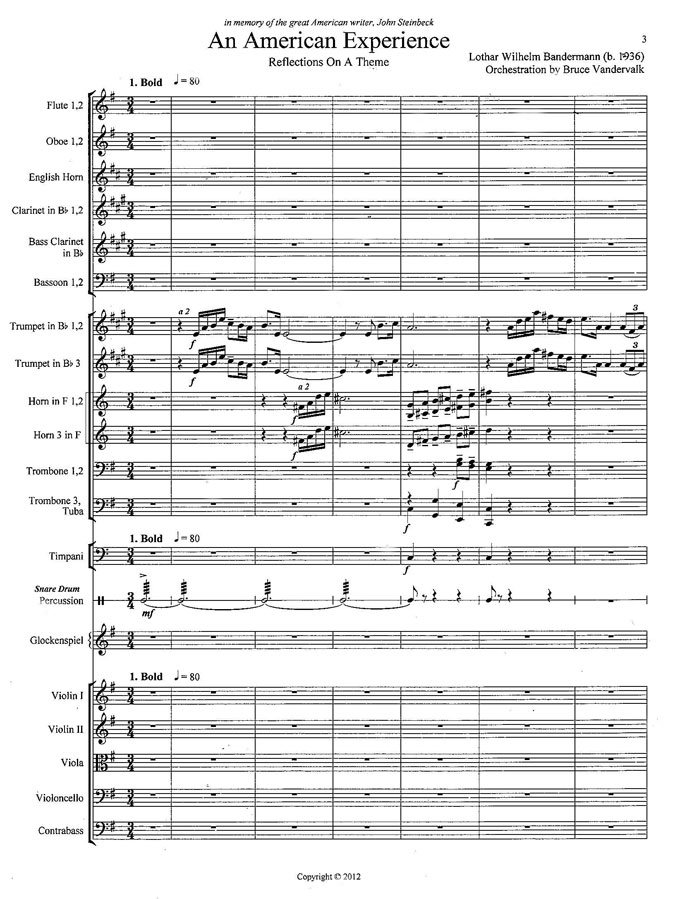

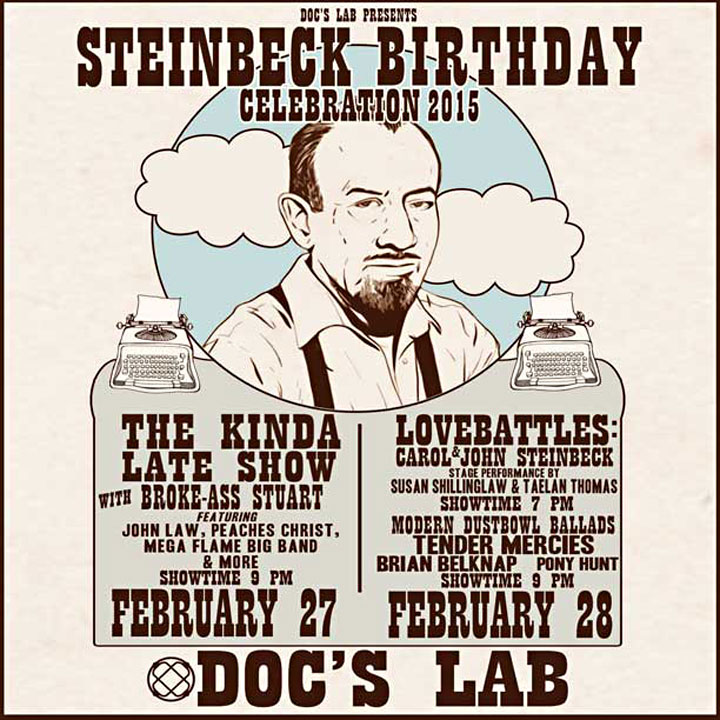

John Steinbeck continues to inspire exciting music by living composers. The latest example is Lothar Bandermann’s “An American Experience: Reflections on a Theme,” an 11-minute set of variations depicting American characteristics and dedicated to John Steinbeck. The orchestral version of the composition—premiered by California’s Silicon Valley Symphony in 2013—will be performed by the Saratoga Symphony at Union Church of Cupertino, California, on May 3. Organ and orchestral versions of “An American Experience” can be heard on the composer’s website. The work is also arranged for symphonic band.

John Steinbeck continues to inspire exciting music by living composers. The latest example is Lothar Bandermann’s ‘An American Experience: Reflections on a Theme.’

Lothar Bandermann shares traits with John Steinbeck beyond the German heritage evident in both names: working-class roots and a love of organ music. Born into a coal miner’s family near Dortmund, Germany, the Cupertino, California-based composer came to the U.S. in 1958 at the age of 24, graduating from the University of California with a major in physics and receiving a doctorate in space physics from the University of Maryland. After conducting astronomy research and teaching at the University of Hawaii—where he met and married Billie Lanier Reeves, a singer and choir director—he worked as an aerospace scientist in Palo Alto, California, before retiring in 1998 to devote his time to writing and performing sacred music.

Lothar Bandermann shares traits with John Steinbeck beyond the German heritage evident in both names: working-class roots and a love of organ music. Born into a coal miner’s family near Dortmund, Germany, the Cupertino, California-based composer came to the U.S. in 1958 at the age of 24, graduating from the University of California with a major in physics and receiving a doctorate in space physics from the University of Maryland. After conducting astronomy research and teaching at the University of Hawaii—where he met and married Billie Lanier Reeves, a singer and choir director—he worked as an aerospace scientist in Palo Alto, California, before retiring in 1998 to devote his time to writing and performing sacred music.

Bandermann shares traits with Steinbeck beyond the German heritage evident in both names: working-class roots and a love of organ music.

Like John Steinbeck, he took piano lessons as a boy, playing the organ at his Catholic church when he was 15, a lifelong practice he continues as organist for St. Joseph of Cupertino Catholic Church near his California home. Although he has composed numerous sacred works for piano, voice, and choir—including a Latin Requiem for solo, chorus, organ, and orchestra—he concentrates on writing and arranging organ music, 400 examples of which he can be heard performing on his website. The organ original of “An American Experience” will be published by Zimbel Press in 2015, and new projects are in the works. Piano, organ, orchestra, choir, symphonic band: John Steinbeck would admire the versatility of this industrious German-born scientist-musician in tune with the American experience celebrated (and criticized) by John Steinbeck, a sophisticated music lover who liked new music.

John Steinbeck would admire the versatility of this industrious German-born scientist-musician in tune with the American experience.

Union Church is located at 20900 Stevens Creek Boulevard in Cupertino, California. The May 3 concert, a Sunday event, begins at 3:00 p.m.