This is the year of The Grapes of Wrath—its 75th anniversary—and the cause for self-reflection for readers of John Steinbeck, including me. My version is both personal and professional. I teach at San Jose State University, one of the world’s top centers of John Steinbeck research, and for the second time I am serving as interim director of the University’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies while Nicholas Taylor, the permanent director, is on leave.

This is the year of The Grapes of Wrath—its 75th anniversary—and the cause for self-reflection for readers of John Steinbeck, including me. My version is both personal and professional. I teach at San Jose State University, one of the world’s top centers of John Steinbeck research, and for the second time I am serving as interim director of the University’s Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies while Nicholas Taylor, the permanent director, is on leave.

John Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University

When I accepted the same post on a permanent basis in 2005, I was—to be frank—wet behind the ears, despite my apprenticeship 10 years earlier filling in for Susan Shillinglaw, the Steinbeck Studies Center director, during her sabbatical. I had a solid enough background teaching and writing about American Modernism, the era that includes John Steinbeck, although too often Steinbeck is ignored in academic discussion of his less popularly-read contemporaries such as Willa Cather, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, and T.S. Eliot. But I made some embarrassing errors anyway—like revealing my lack of familiarity with the 1950 stage production of Burning Bright, Steinbeck’s third, last, and least-successful experiment with the play-novella form following Of Mice and Men and The Moon Is Down.

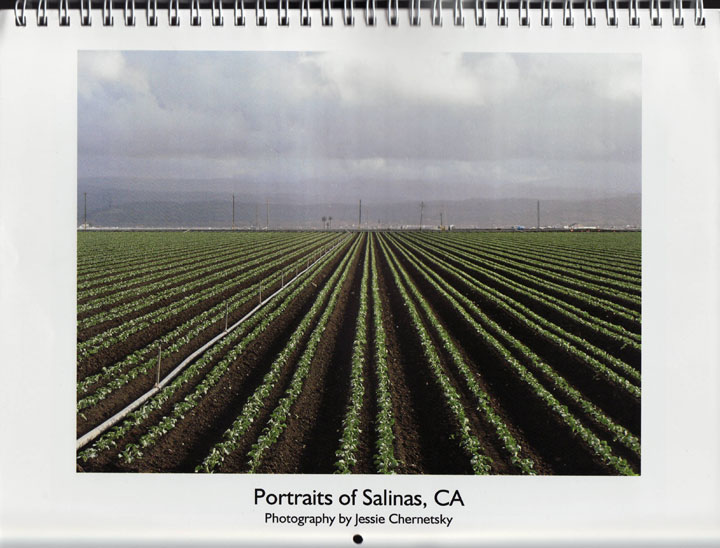

Of course, I had huge shoes to fill when I became the permanent director in 2005. Susan Shillinglaw’s stature as a John Steinbeck scholar was enormous when she stepped down as director of the Center at San Jose State University, where she continues to teach, and it has continued to grow. Part of my learning curve in her footsteps was to deepen my knowledge of John Steinbeck’s life and work, particularly the agony and transcendence embodied in The Grapes of Wrath—a book that continues to create more heat than light for certain readers in Oklahoma and California, and the excuse for latter-day book-banning in places where controversial classics such as Huckleberry Finn are deemed morally unwise or politically incorrect.

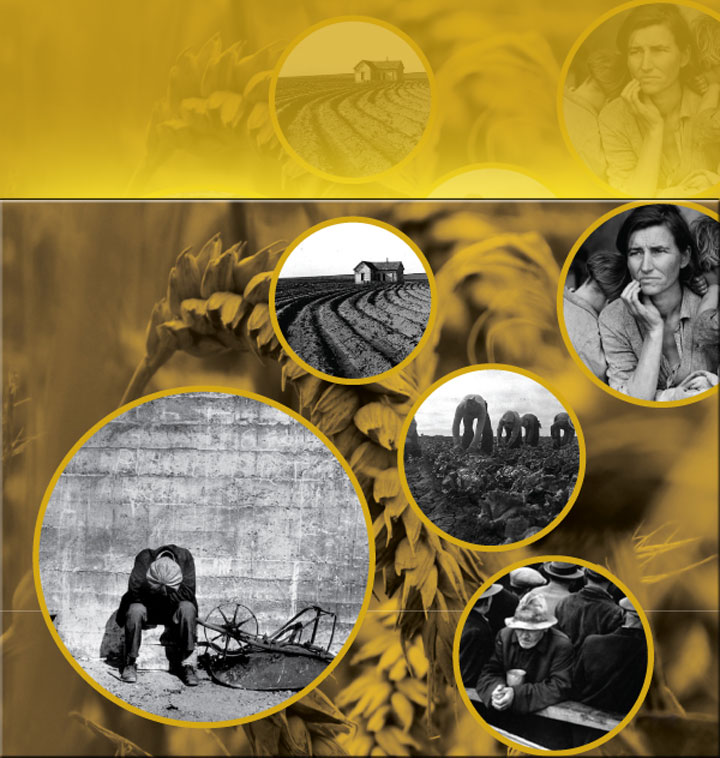

Celebrating The Grapes of Wrath in Pictures and in Words

Celebrating The Grapes of Wrath in Pictures and in Words

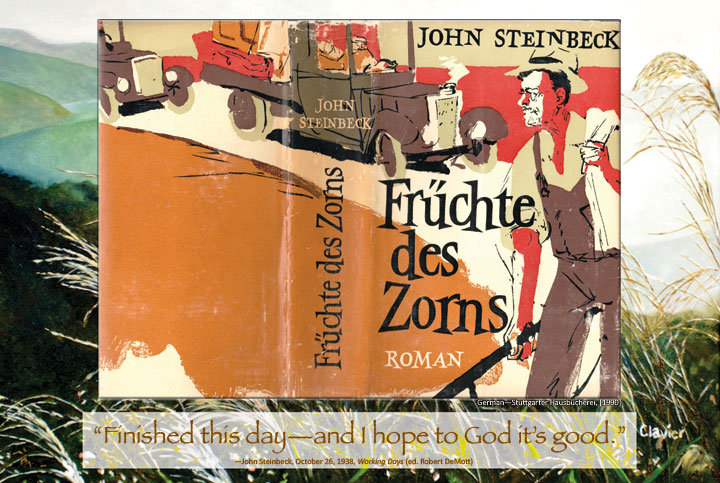

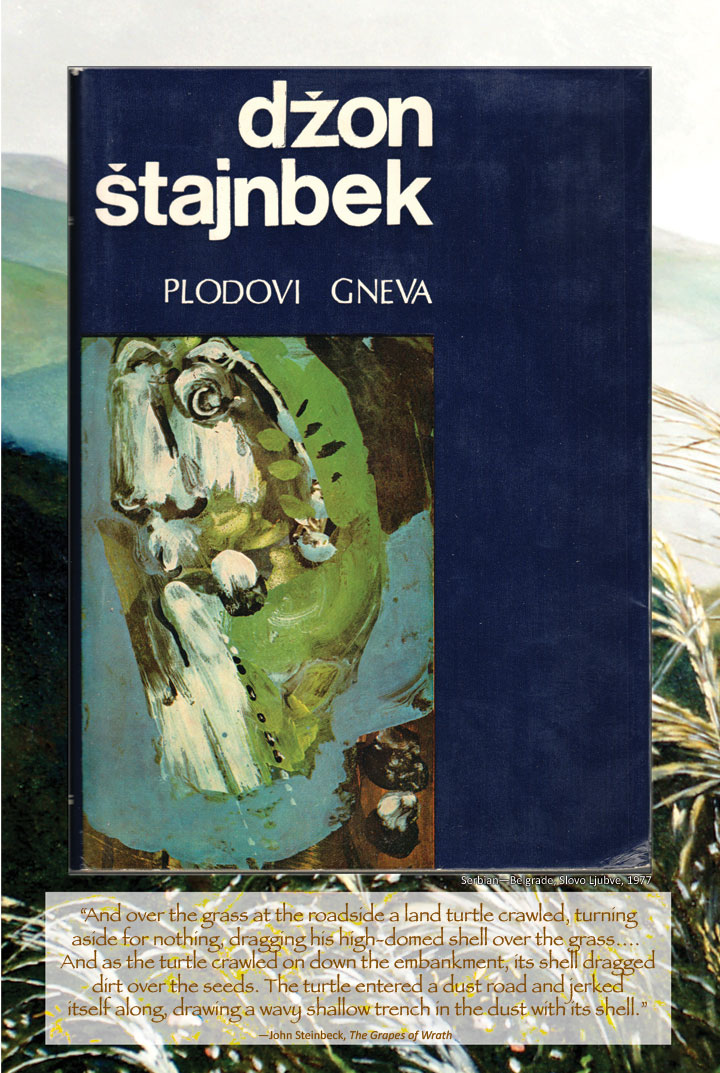

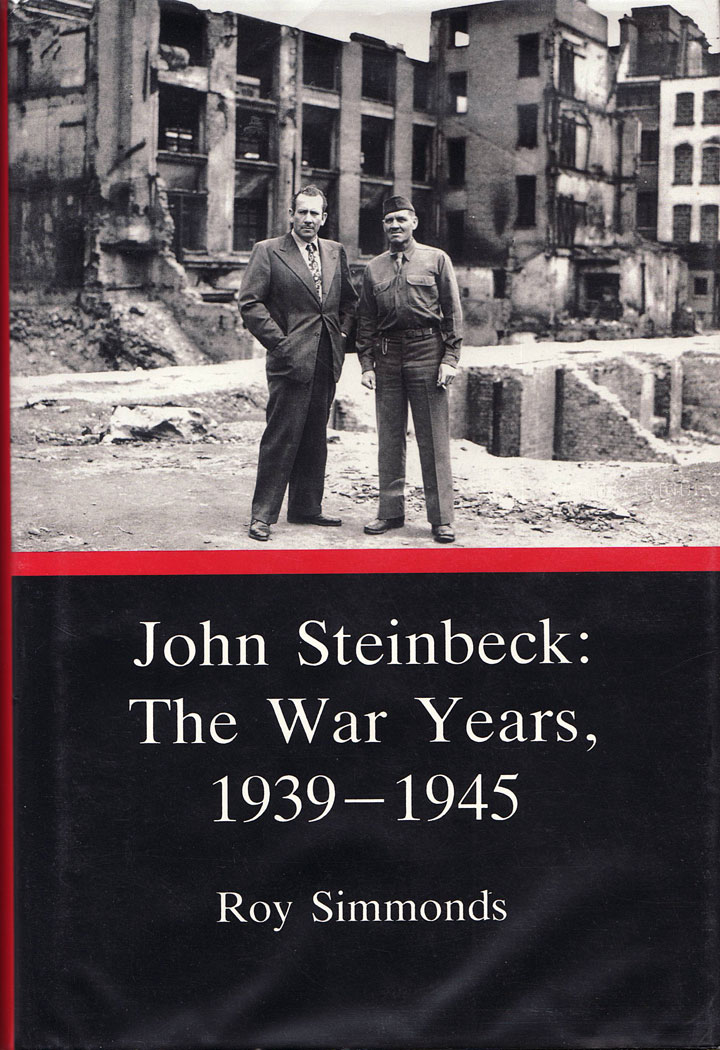

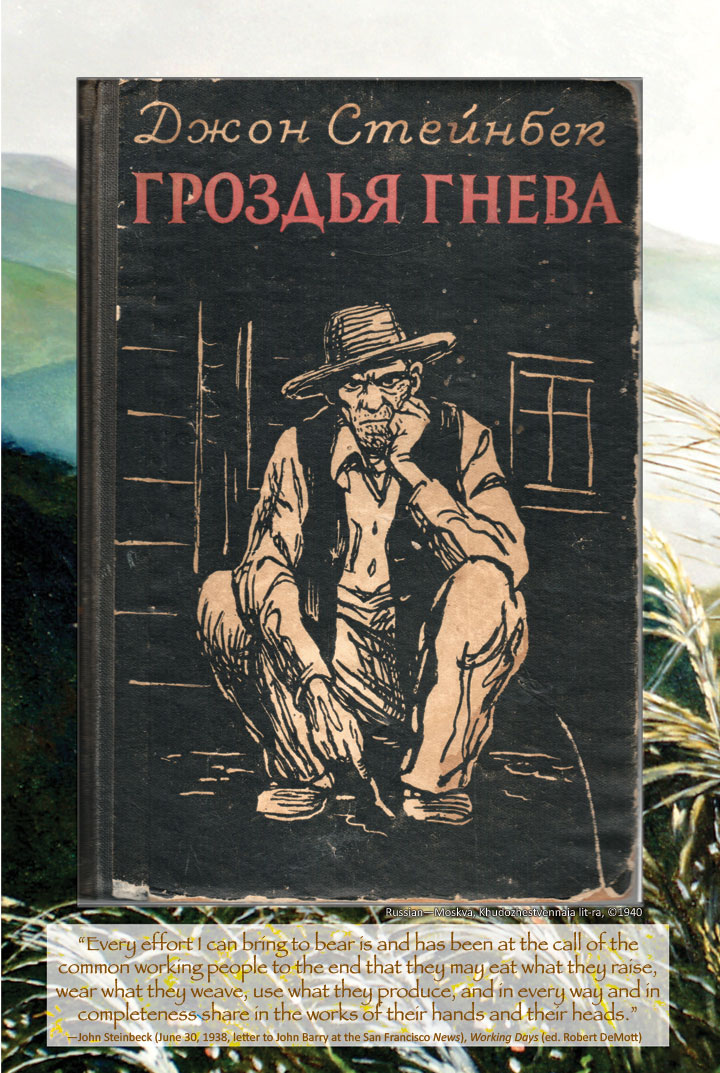

When Viking Press published The Grapes of Wrath on April 14, 1939, John Steinbeck became a national celebrity. The following year his book won the Pulitzer Prize, John Ford made the movie starring Henry Fonda, and Steinbeck’s notoriety spread throughout a world already at war. To mark the 75th anniversary of the novel’s debut on the international stage this month, San Jose State University will sponsor a series of celebrations in honor of Steinbeck’s masterpiece—a work that is integral to California history, relevant to American society, and as well known as Huckleberry Finn to readers as far away as Russia and Japan.

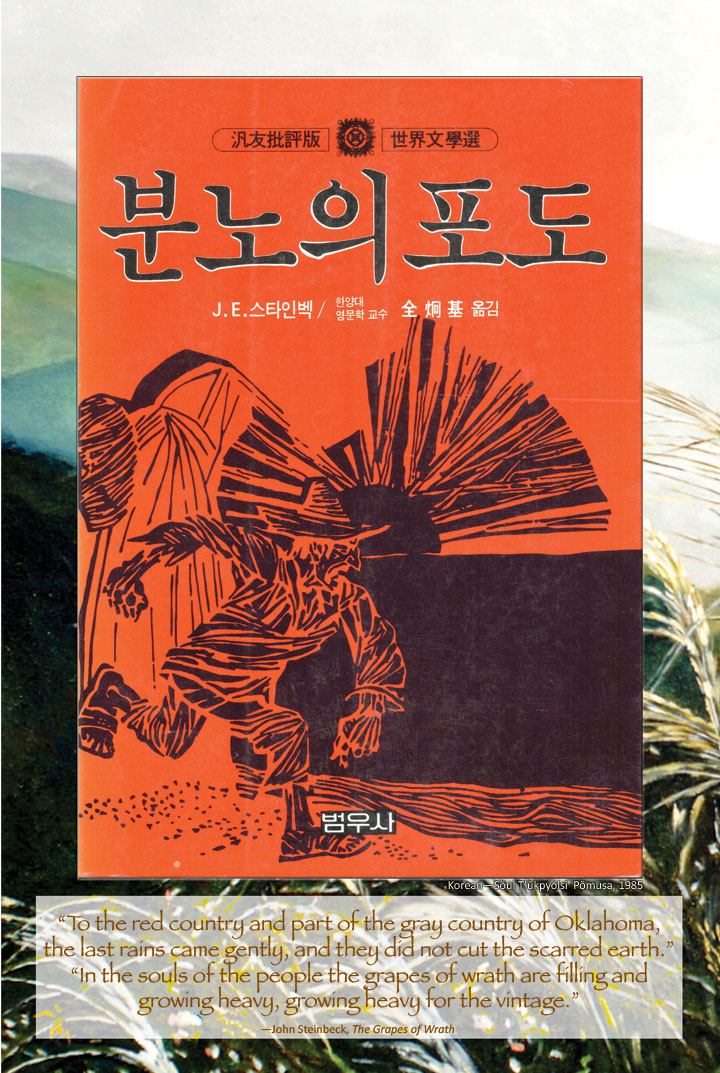

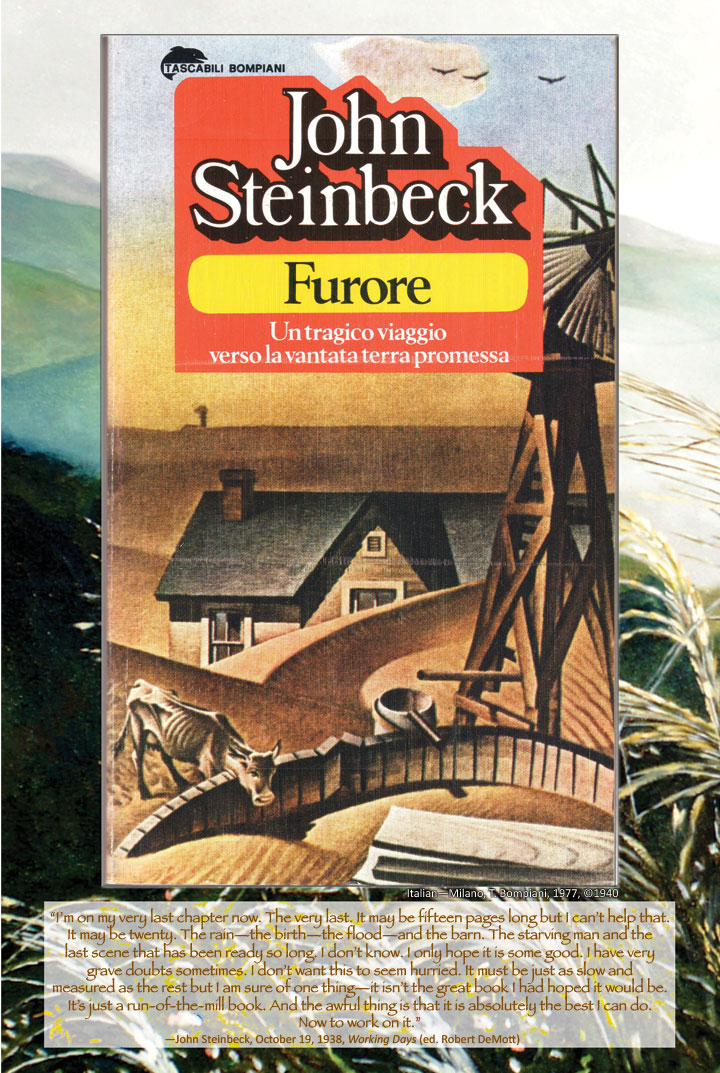

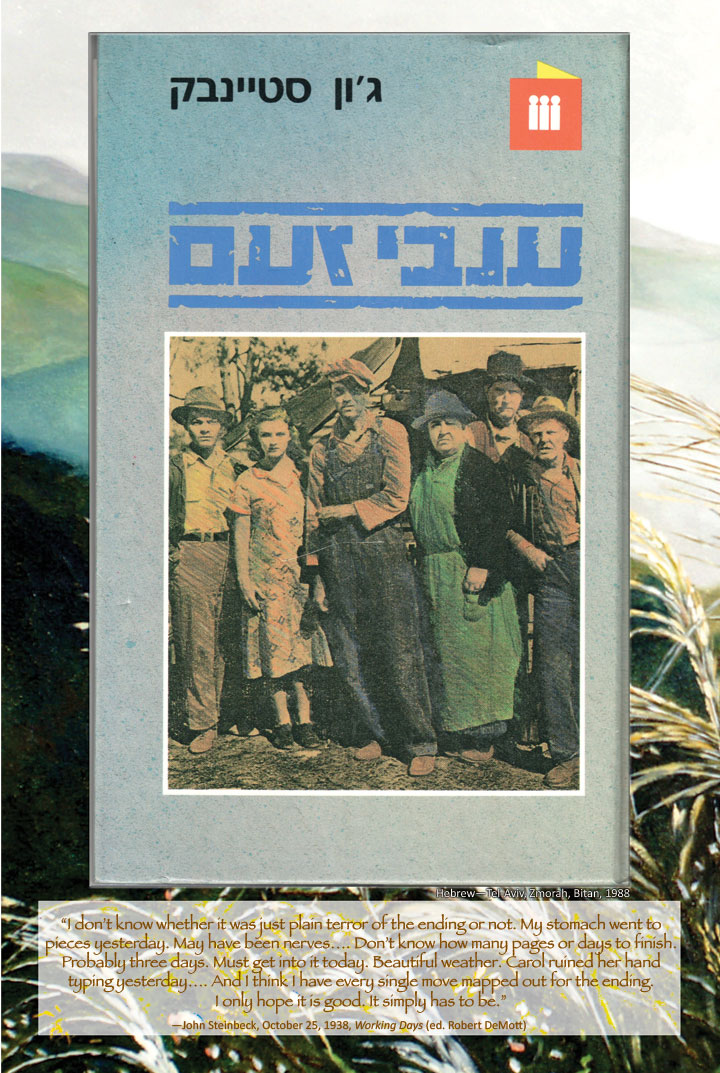

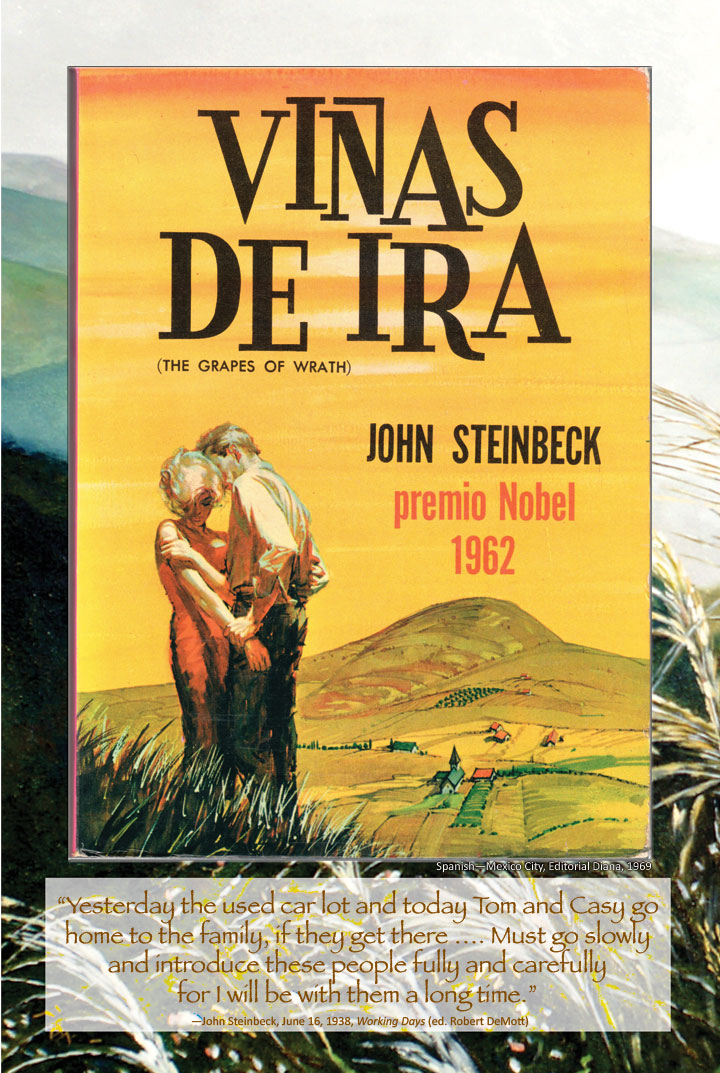

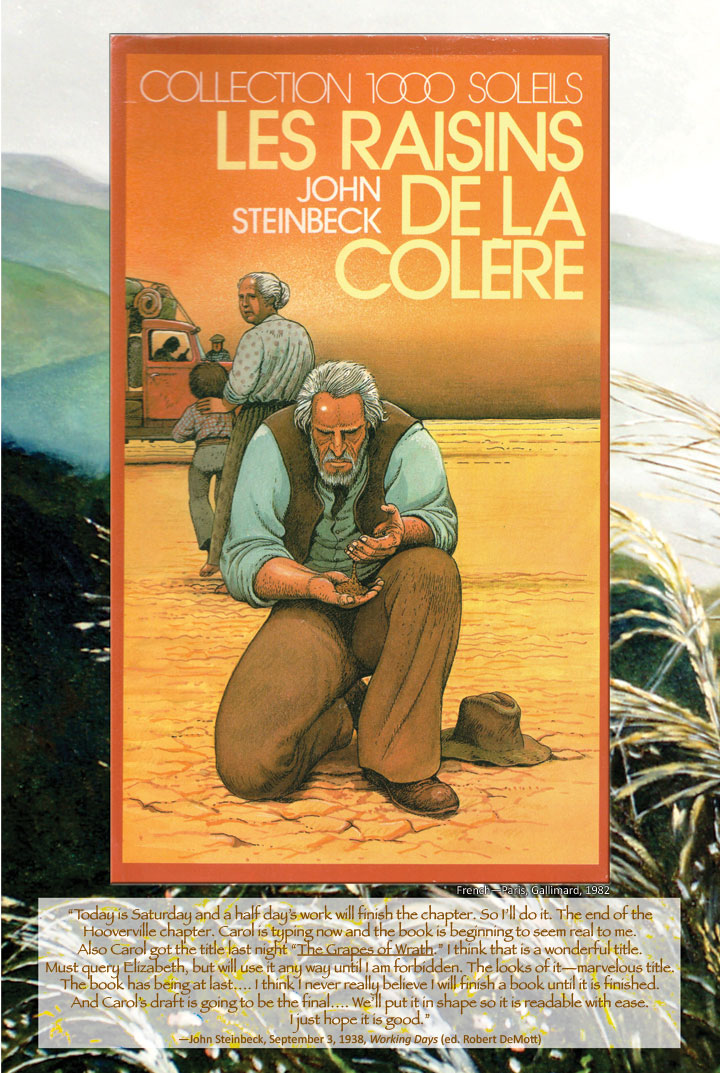

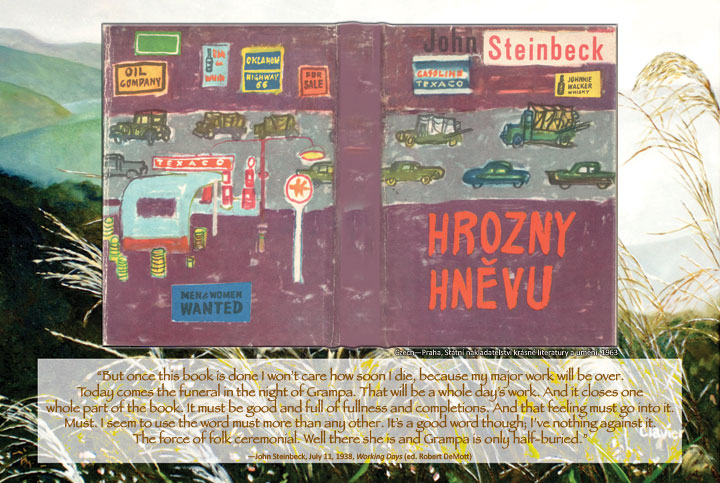

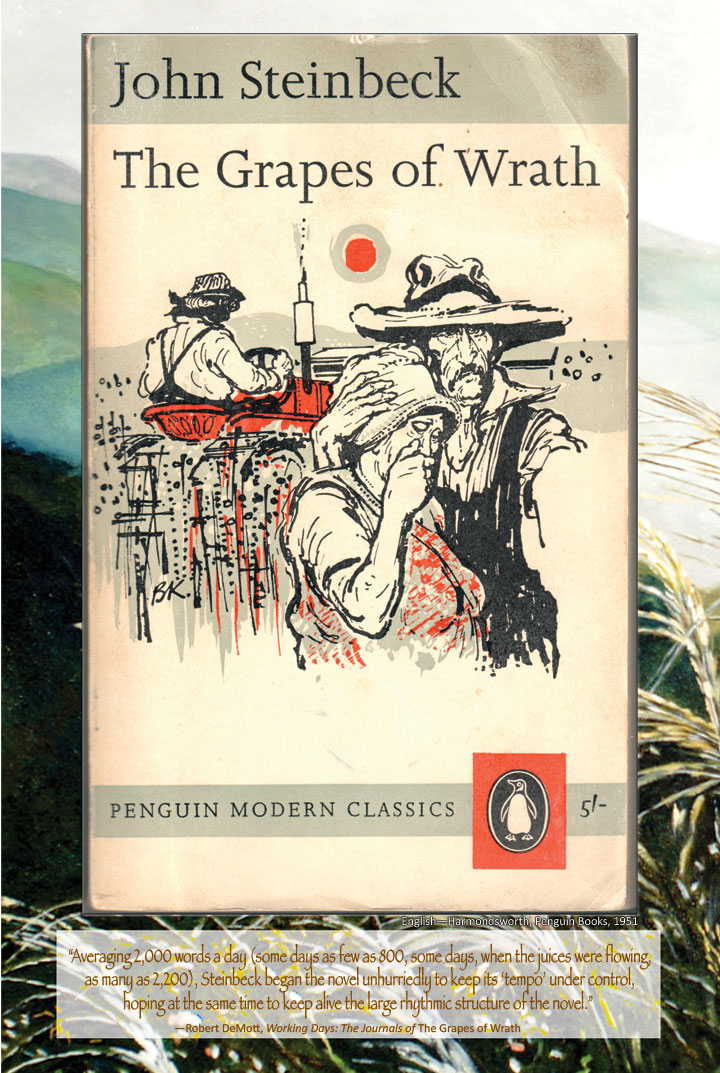

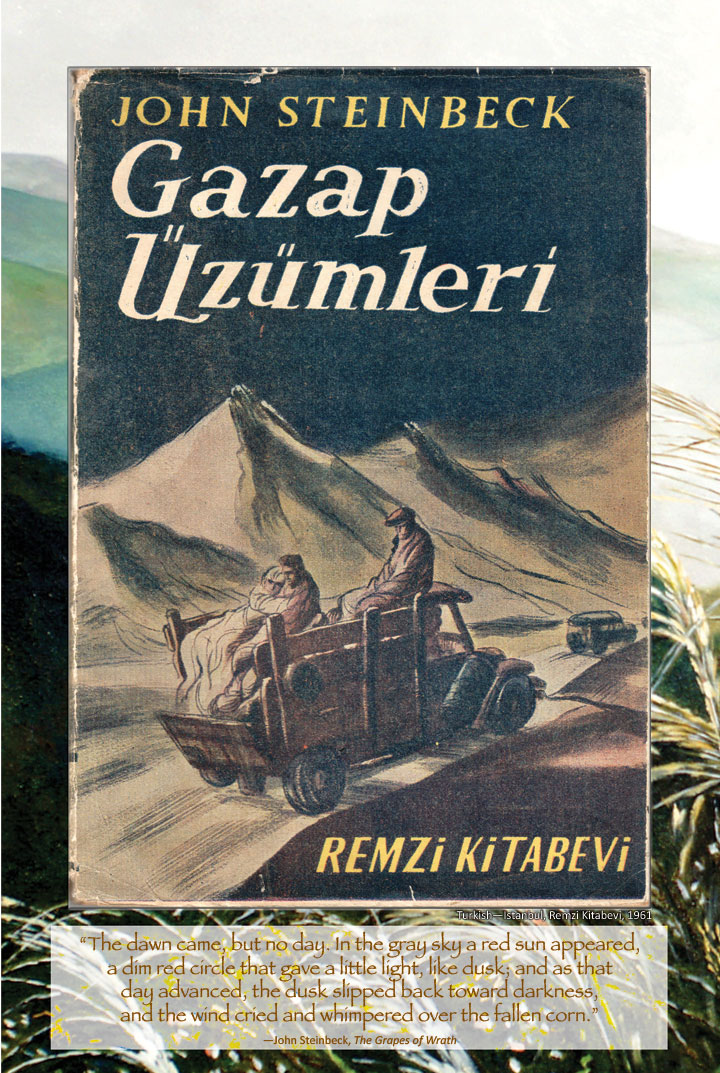

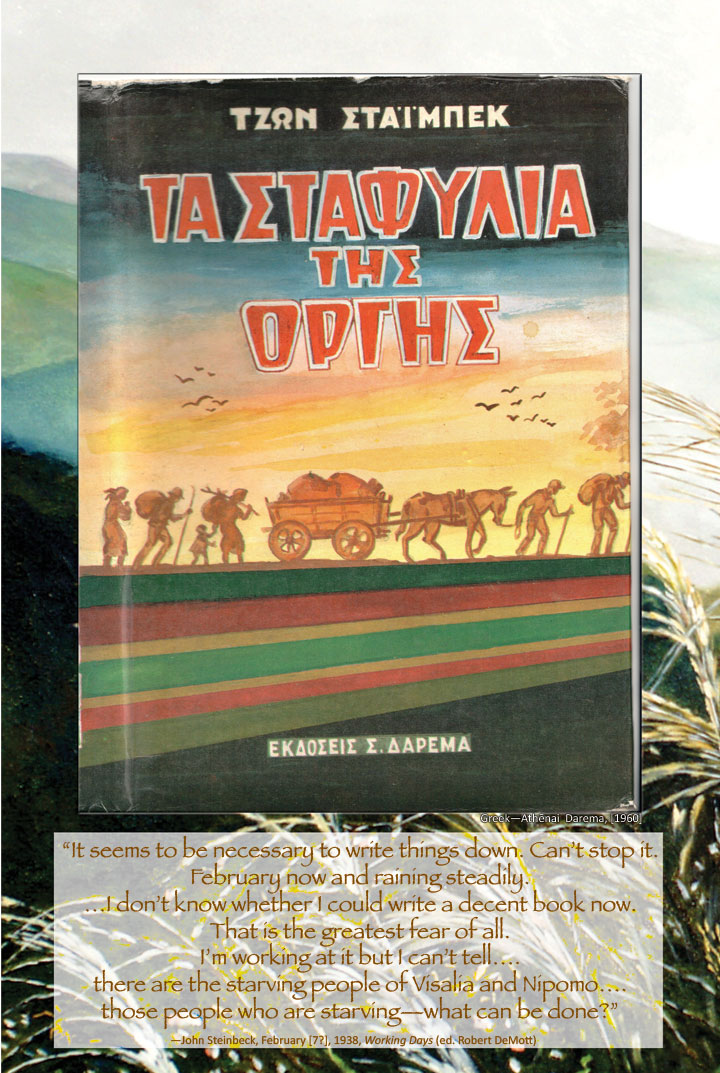

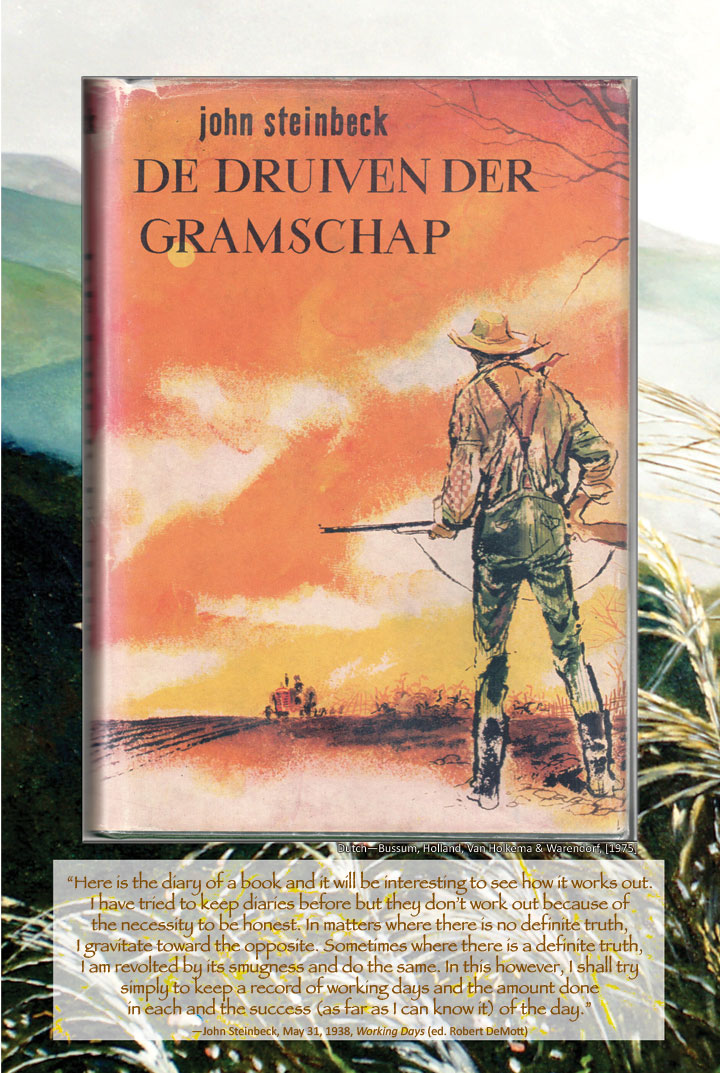

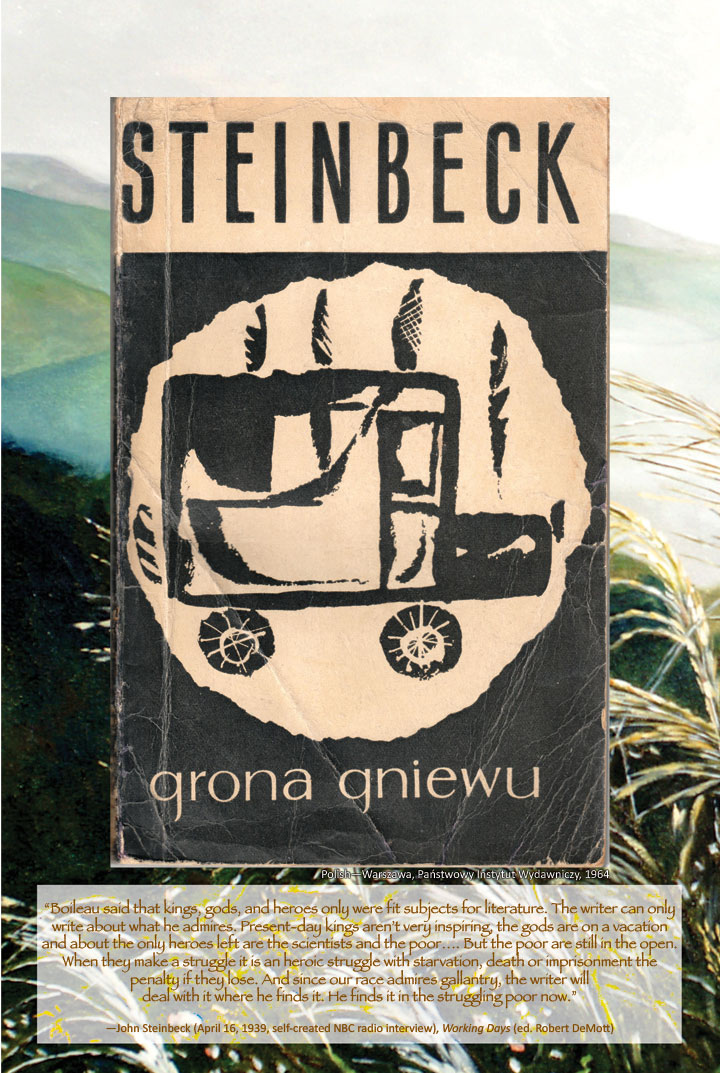

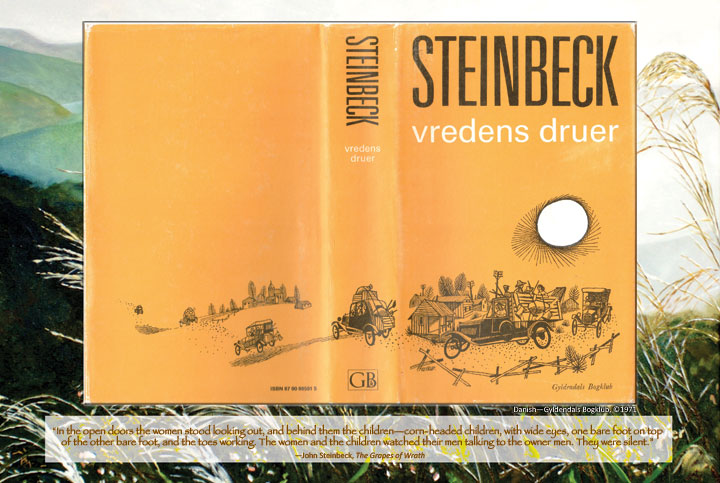

As noted in an earlier post, an exhibition of colorful covers selected from foreign editions of The Grapes of Wrath is currently on display at the Center for Steinbeck Studies. The exhibit, assembled by Archivist Peter Van Coutren, is accompanied by information about the novel and its background. I recommend it to anyone visiting the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library on the San Jose State University campus.

Thanks to the efforts of San Jose State University faculty members such as Scot Guenter, the SJSU Campus Reading Program will sponsor a Grapes of Wrath “readathon”—a public performance of the entire novel, starting at 6:00 p.m. on April 16 and ending 24 hours later, more or less. Individuals who participate as readers will receive a gift, along with listing on the Spartans Care Read-a-thon Honor Roll. (In case you’re wondering, “Spartans” is the designation for San Jose State University’s sports teams.) Signing up is easy.

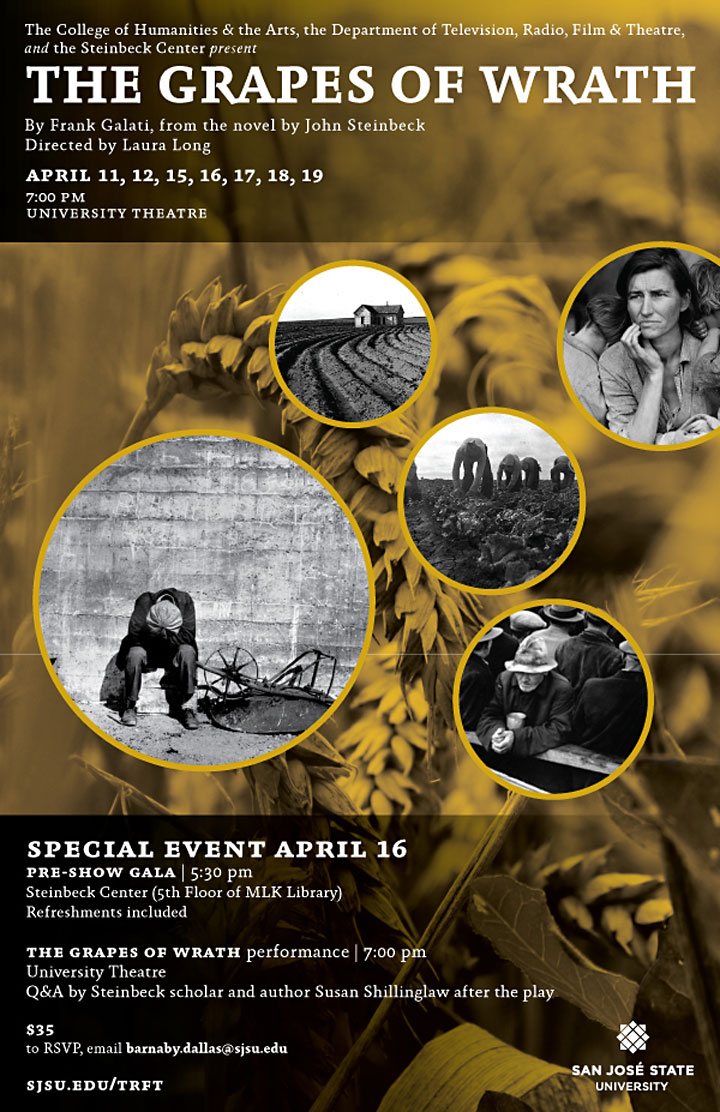

Reprising the Stage Version of Steinbeck’s Masterpiece

Reprising the Stage Version of Steinbeck’s Masterpiece

Thanks to the hard work of David Kahn, the chair of San Jose State University’s Department of TV, Radio, Film and Theater Arts, and his colleague Barnaby Dallas, the Coordinator of Productions, a main attraction will be the stage production of The Grapes of Wrath at the Hal Todd Theatre on the San Jose State University campus. The play—Frank Galati’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel—is directed by Laura Long and runs April 11-12 and April 15-19. The April 16 performance features a pre-performance reception and a post-play “talkback” with Susan Shillinglaw about her new book On Reading The Grapes of Wrath. Tickets can be purchased online.

Galati’s adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath premiered at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater in 1988 and ran for three years. It also traveled to London and New York, where it won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for best play of 1991. Galati received two 1990 Tony Awards—Best Play and Best Direction—for his work, which also garnered a half-dozen acting award nominations for cast members Gary Sinise, Terry Kinney, and Lois Smith. Galati, a former professor at Northwestern University, was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in 2004. San Jose State University produced his Grapes of Wrath in the 1990s, so this month’s run is a celebratory reprise.

In May there will be more—but I’ll save that for another time. Who said April was the cruelest month? At San Jose State University, it’s the coolest—thanks to John Steinbeck and The Grapes of Wrath.