Tom Lorentzen, a retired nonprofit executive in Castro Valley, California, brought John Steinbeck back to life literally on August 24 at a private event billed as “John Steinbeck—in Search of America” and attended by 175 members of a San Francisco Bay Area social club. Impersonating Steinbeck at the age when Travels with Charley and America and Americans were written about a nation rocked by scandal and strife, Lorentzen employed an original idea to dramatize the imaginary conversation of Steinbeck—back from the dead—with Rich, a young logger encountered by the author in an Oregon redwood grove during the fabled road trip across the country from which Steinbeck said he had begun to feel alienated. Now 80, Rich uses a search engine time-travel device to conjure Steinbeck and pose the question he failed to ask when they met in the woods in 1961. What’s so great about America? Lorentzen (in photo) is a former board member of the National Institute of Museum Services. Like Steinbeck, who served on the board that became the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, he remains bullish on America’s future, despite problems that Steinbeck would recognize and acknowledge if, age 115, he were alive today.

Book Signing: Short Stories Based on Steinbeck’s Life

The National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California, John Steinbeck’s home town, will host the first official book signing for Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, short stories based on Steinbeck’s life by the playwright and fiction writer Steve Hauk, 5:30-6:30 p.m. on Friday, September 1, in the center’s museum at One Main Street in downtown Salinas. Book news travels fast in Steinbeck country, and Hauk will answer fans’ questions about the origin and inspiration for the stories, which dramatize actual and imagined episodes from Steinbeck’s boyhood and years coping with fame, friends, and enemies in Salinas, Monterey, and New York. Published only one month ago, Steinbeck: The Untold Stories is already on display at the National Steinbeck Center and the Steinbeck House in Salinas, River House Books in Carmel, the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in San Jose, the Monterey Public Library, and BookWorks in Pacific Grove, the setting for several of the short stories. Common Good Books, the “live local, read large” bookstore associated with Garrison Keillor in St. Paul, Minnesota, also stocks Steinbeck: The Untold Stories.

Photo courtesy of BookWorks.

A Travel Blogger Considers American Self-Identity on a Visit to Salinas, California

The recent visit my wife Elizabeth I made to Salinas, California included a stop at John Steinbeck’s boyhood home. It brought back a flood of memories, and it made me think about self-identity. That felt right in the moment because America’s sense of itself was a major concern of Steinbeck’s writing.

America’s sense of itself was a major concern of John Steinbeck’s writing.

When I was a boy I devoured Steinbeck’s books. By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style. Years later my brother John and I produced travel films and documentaries, and one of the films we made, California: A Tribute, featured a segment on John Steinbeck and the trips to California’s Central Valley that led him to write The Grapes of Wrath. Seeing the Steinbeck House reminded me of the outrage Steinbeck felt about the thousands of dispossessed families from the American Dust Bowl who had made the long trek to California in search of agricultural jobs and a better life, only to find themselves destitute, hungry, and homeless, ready to accept work at any pay so that they could survive and feed their children.

By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style.

On a broader scale, the visit to the Steinbeck House made me think about the course of our nation’s history, about the millions of dispossessed foreigners who came to our shores and borders, fleeing persecution and homelessness and poverty, in search of a better life for themselves and their families, just like John Steinbeck’s American refugees. Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in The Grapes of Wrath—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children, sometimes entire families who have already established themselves in our country. Once upon a time we opened our doors to immigrants. Now we’re closing them.

Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in “The Grapes of Wrath”—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children.

Certainly rules need to be established and followed with respect to immigration. But what is happening now goes beyond rules or regulations. Too many of us are attempting to retreat into a narrow self-identity, building walls against the tide of diversity that has been our distinguishing characteristic as a culture. Who are we as a nation and a people? The comfortable categories of the past are being challenged and shattered in other countries, too, and we feel the same threat to our self-identity that they do. Like John Steinbeck, however, I am optimistic that a new inclusiveness will emerge in the end—the sense of connection and commonality that Steinbeck’s characters achieve in the closing pages of The Grapes of Wrath. The world of the truly human family.

Salinas, California Poetry Slam Invites Submissions

Most Steinbeck books are fiction, but the Salinas, California native also wrote poetry in school and got better grades in versification than he did in short story writing at Stanford. This year’s Big Read poetry slam at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas honors Steinbeck’s gift for verse, and the author’s sensitivity to race and class, with an invitation to writers to compose a poem in response to Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a 2017 Big Read book selection that reflects on racism in America. This is the fourth year the National Steinbeck Center has participated in the Big Read, a community literacy initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts, but the first to feature a poetry slam—the idea of Jenna Garden, a Stanford student and National Steinbeck Center summer intern. Poems submitted by September 5 will be read aloud to a panel of judges who will award cash prizes on September 8. This year’s Big Read in Salinas, California also features a film series at the Maya Cinemas multiplex. The series kicks off August 28 with Lifeboat, the 1944 movie for which Steinbeck, who wrote the script, did not want credit because of racial stereotyping by the director Alfred Hitchcock, a man Steinbeck privately described as a middle-class English snob.

John Steinbeck Loved This Family Home in Watsonville, California, and So Will You

For John Steinbeck, moving on in life meant leaving family homes—and friends—behind in California, starting with Salinas, where the Steinbeck family home on Central Avenue has become a living museum made possible in part by gifts of memorabilia from John Steinbeck’s oldest sister, Esther. The 11th Street cottage in Pacific Grove where Steinbeck often stayed when he was poor, single, or hurting remains in the extended family, but the pair of houses in Los Gatos where he lived with his wife Carol and wrote the books that made him famous both belong to strangers now. The bungalow he bought on Eardley Avenue in Pacific Grove when the marriage faltered and he needed writing space belongs to a bed and breakfast today, but it can be rented and is readily seen from the street. So is the historic adobe in Old Monterey that Steinbeck purchased with his second wife before abandoning California for New York, where he chose to live with Elaine, his third wife, until he died.

Visit Rodgers House at Santa Cruz County Fairgrounds

Through it all, the family home John Steinbeck kept coming back to was his sister Esther’s house in Watsonville, California, the Pajaro Valley farming community nestled between the mountains and the sea northwest of Salinas, along the Monterey-Santa Cruz county line. Esther moved there to teach before marrying Carrol Rodgers, a prosperous rancher-farmer, and raising three daughters who called John Steinbeck uncle. The Rodgers family home on East Lake Avenue, built in the 1870s by Esther’s husband’s forebears, was bigger than any of the houses owned by Steinbecks in Salinas, Los Gatos, or Pacific Grove, but it was warm and inviting and popular with extended family members, including John. Though John Steinbeck became controversial and Carrol Rodgers remained distant, Esther loved her brother and welcomed him when he came to Watsonville. Evidence that Steinbeck enjoyed visiting the Rodgers household, wherever he happened to be living at the time, can found in letters and photographs from the 1930s to the 1960s on view at the home. After Esther died, friends and family members stepped in to preserve the house and move it to the Santa Cruz County Fairgrounds, where it’s open to the public by appointment. Call 831-724-5671.

Interior photo of Rodgers House today courtesy Dale Bartoletti.

American Literature Conference Considers Steinbeck in War and Peace

A pair of panels at the annual conference of the American Literature Association, held May 25-28, 2017 in Boston, Massachusetts, examined aspects of John Steinbeck’s writing in times of war and peace. Thomas Barden, professor emeritus at the University of Toledo, discussed race and racism in Lifeboat, Steinbeck’s World War II novella-screenplay, while Douglas Dowland of Ohio Northern University focused on the dispatches and letters Steinbeck wrote from Vietnam 20 years later. Steinbeck’s novels were also the subject of attention by speakers: To a God Unknown (Ryan Schlesinger, University of Tulsa); Cannery Row and Sweet Thursday (Christian Gallichio, University of Massachusetts-Boston), and Of Mice and Men (Lori Whitaker and Mimi Gladstein, University of Texas-El Paso). The focus of four single-author websites devoted to his life, work, and influence, John Steinbeck was featured at annual conferences of the American Literature Association in San Francisco in 2012 and again in 2016.

Bill Lane Center at Stanford University Examines John Steinbeck, Environmentalism

John Steinbeck and the environment was the subject of a May 10 symposium held at Stanford University and attended by students, teachers, and others. Guest speakers for the campus event, sponsored by the Bill Lane Center for the American West, included Susan Shillinglaw, William Souder, and members of the Stanford University faculty. The late Bill Lane—the legendary publisher and philanthropist for whom the Center for the American West is named—was born in Iowa in 1919, the year Steinbeck entered Stanford as a freshman. Lane also attended Stanford before building a lucrative publishing empire around Sunset Magazine, a Lane family enterprise headquartered in Menlo Park, California. A Teddy Roosevelt Republican (like Steinbeck’s parents), Lane was a leader in the movement to protect pristine California wilderness from commercial development by acquiring it privately and putting it into public trust. Follow this video link learn more about John Steinbeck as an environmentalist.

The House Where Steinbeck Lived and Wrote Needs Help

John Steinbeck was born on February 27, 1902 in the front bedroom of the Victorian house at 132 Central Avenue in Salinas, California. In 1905 he was christened in the parlor of the Queen Anne-style structure—the same room where he later practiced the piano. In the living room he announced that he intended to become a writer. In the basement he regaled neighborhood friends with ghost stories and other tales. In an upstairs bedroom he wrote short stories that he sent to magazines, unsigned, as a teenager. He left for Stanford in 1919; years later he and his wife Carol returned to help care for his dying mother, a former school teacher who insisted that all four of her children go to church, learn piano, and attend college. In the same upstairs bedroom he occupied as a boy he continued to work on The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat, the book that brought him fame when it was published in 1935, the year his father died.

In the upstairs bedroom Steinbeck occupied as a boy he continued to work on The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat, the book that brought him fame when it was published in 1935, the year his father died.

The home was sold following Olive’s death, near the bottom of the Great Depression, in 1934. For the next four decades—years of war, recovery, and modernization—ownership of the aging Victorian house passed through various hands until its purchase by the newly created Valley Guild in 1973. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization created to save the house where Steinbeck was born, the Valley Guild made repairs, conducted research, and produced results that are evident today. The bed in which Steinbeck was born was returned. So were Olive’s desk and table. Steinbeck’s sisters stayed in California, and they and their children and grandchildren made generous gifts of period furnishings and family heirlooms. Thanks to the hard work of Valley Guild volunteers, the Steinbeck House was added to the National Register of Historic Places, a prestigious designation with some practical benefits.

For the next four decades—years of war, recovery, and modernization—ownership of the aging Victorian house passed through various hands until its purchase by the newly created Valley Guild in 1973.

Recognizing the need for an income stream to support ongoing maintenance and preservation, the founders put their heads together and came up with a plan that serves educational and economic goals equally. For five days each week throughout the year the House is open to the public as a lunch restaurant, gift shop, and bookstore operated by a team of 98 dedicated volunteers. The restaurant employs a professional chef and offers a changing menu. Table service is provided by Valley Guild members in period dress—docents in motion who educate diners about Steinbeck while taking orders and serving food. The annual Steinbeck festival and the National Steinbeck Center on Main Street, three blocks from the Steinbeck House, are partners in the enterprise of keeping Salinas, California at the forefront of global interest in Steinbeck’s life and work.

Time Catches Up With Every Victorian—Even Steinbeck’s

Age has its advantages, but keeping a 119-year-old Victorian house in working order is expensive. Not long ago it was discovered that the center of the Steinbeck House, supported by eight posts on brick footings, was slowly sinking. The posts run the length of the basement gift shop and bookstore and serve as the building’s legs. As they go, so goes the body. To prevent collapse, soil engineers and construction experts determined that the deteriorating posts and bases had to be replaced using concrete. Although the restaurant has remained open during the process, the project required closing the gift shop and book store, raising the central beams, and installing temporary supports while making excavations and constructing permanent posts and footings—all necessary to insure the future of John Steinbeck’s birthplace as a public resource.

Using the GoFundMe Page Makes Giving Safe and Easy

The project is well along and, once all expenses are paid, is expected to cost $35,000. The bill, along with the revenue hole caused by the gift store closing, has created an urgent need for funds to keep the Steinbeck House open and operating in the black. The people of Salinas, California are community-minded and do their part. But the Steinbeck House is a national treasure, and help is also needed from friends and fans who live elsewhere. Fortunately this group is growing: visitors from 68 countries and 50 states have enjoyed lunch and a lesson in Steinbeck history while eating at the restaurant. Please do your part to keep the Steinbeck House on its feet. Visit the new GoFundMe page and make your tax-deductible gift to the project. The Victorian house where Steinbeck first wrote fiction is getting on, but just as beautiful as the day Steinbeck was born in the front room of his family home 115 years ago.

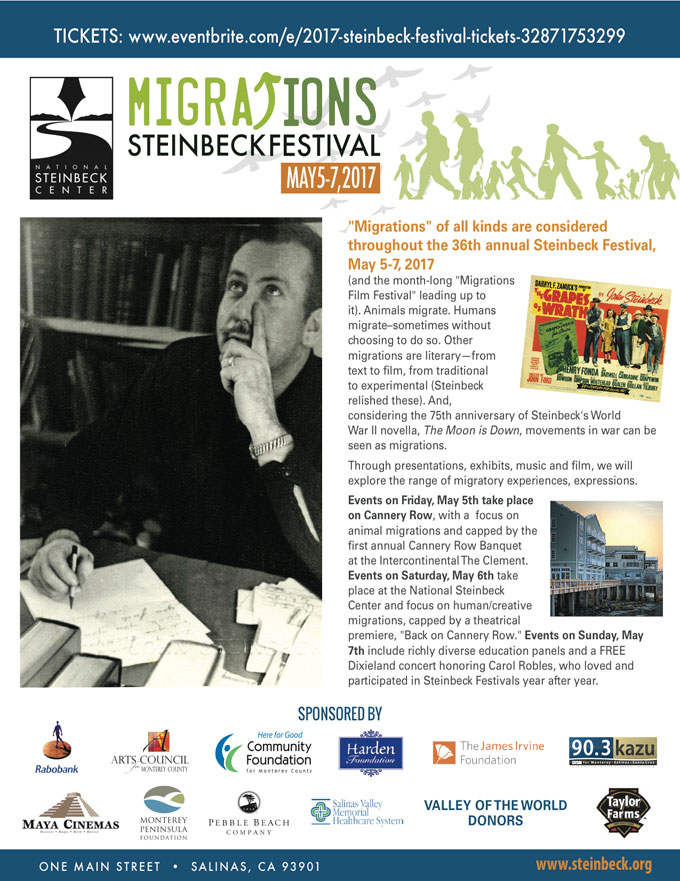

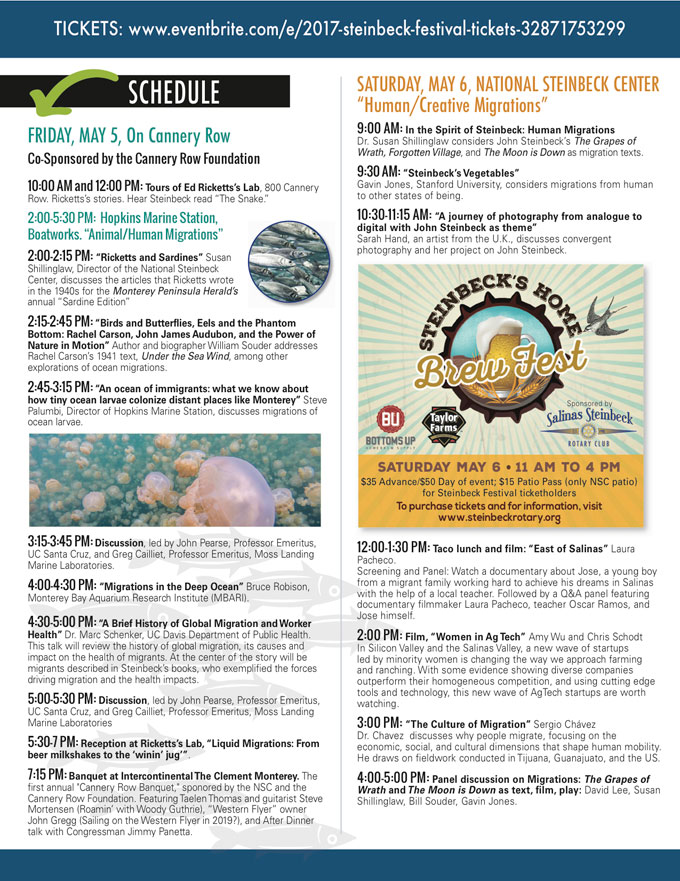

Birds Do It, Bees Do It, and John Steinbeck Did It, Too

Movement was a major feature of John Steinbeck’s life and writing, and migration—human, animal, vegetable—is the focus of this year’s John Steinbeck festival in Salinas, California, scheduled May 5-7 to coincide with Cinco de Mayo, a favorite fiesta of the country Steinbeck visited often in the 1930s and 40s. Like the author himself, the 2017 John Steinbeck festival is peripatetic, moving between Salinas, Monterey, and Cannery Row, as Steinbeck did when he was writing the California books that made him famous. A three-day pass costs $180 and covers most Friday, Saturday, and Sunday events. A special concert in honor of the late Carol Robles—a frequent flyer and legendary tour planner—is free and features Dixieland music, an appropriate choice for a festival dedicated to John Steinbeck, a traveling man who loved jazz.

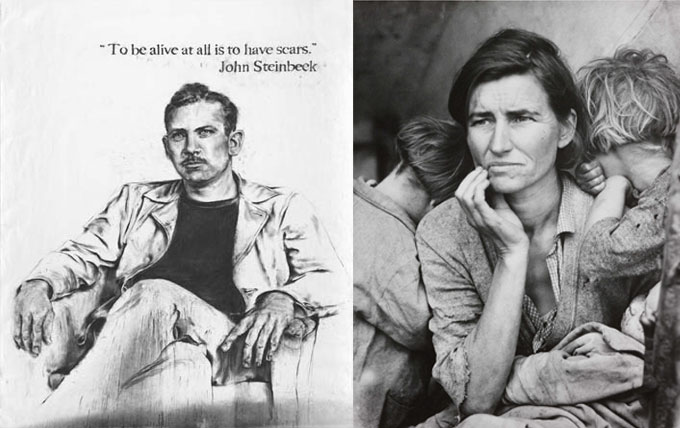

Yale University Brings the Great Depression Home

Yale University has launched Photogrammar, a handy interactive website that pairs images of the Great Depression from the Library of Congress photo archive with the photographers who took them and the places where they were taken. Like The Grapes of Wrath, the photographs of Dorothea Lange and others were intended to educate, engage, and convince average Americans that the poor were human, too. Commissioned by the U.S. Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information and assembled between 1935 and 1945, the 170,000-piece photo archive—like the California migrant camp celebrated by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath—provides eloquent testimony of government’s power to do good, despite naysayers from the right, when disasters occur. The ambitious Yale University project was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a 40-year old federal agency that will disappear if Donald Trump’s proposal to defund the arts and humanities—along with safety-net social programs like Meals on Wheels—is approved by Congress.