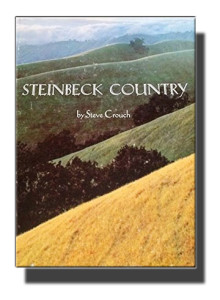

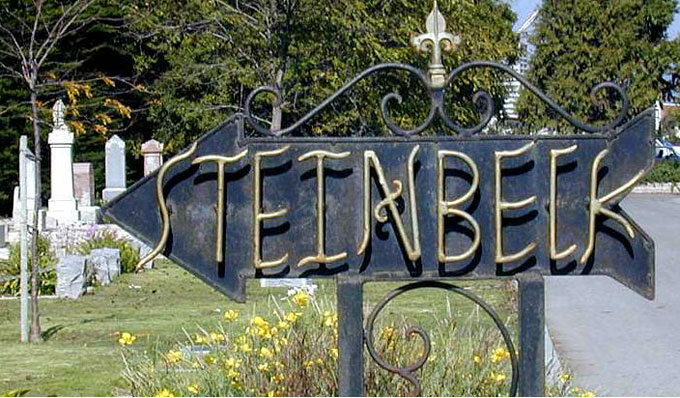

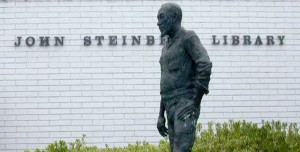

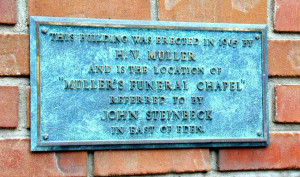

A travel feature in the February 9 New York Times focused on food and wine in Carmel-by-the-Sea and Salinas, California also paid respects to East of Eden, John Steinbeck’s fictional account of bygone days in the Salinas Valley, where agriculture is still king. If you enjoy eating, drinking, and Steinbeck in that order, What to Find in Salinas Valley: Lush Fields, Good Wine and, Yes, Steinbeck is worth your time, whether your summer travel plans include grazing your way through Steinbeck Country or packing East of Eden with the lemonade and sandwiches for an afternoon getaway closer to home.

Photograph of the Salinas Valley by David Laws.