Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, short stories about John Steinbeck by Steve Hauk, were plumbed and praised in a recent review, written by Stephen Cooper, connecting Steinbeck’s concept of “collective mind” to the writing of Friedrich Nietzsche. First published by the print journal Steinbeck Review, the article has been turning up at various online outlets, including the Los Angeles Post-Examiner, thanks to Cooper’s reputation as a writer, like John Steinbeck, whose words reward reading whatever the format. “Glimpsing Steinbeck’s ‘Collective Mind’ Through Steve Hauk’s Stories” is worth savoring, even if Nietzsche isn’t your cup of tea.

A Pilgrim’s Progress for Students of John Steinbeck

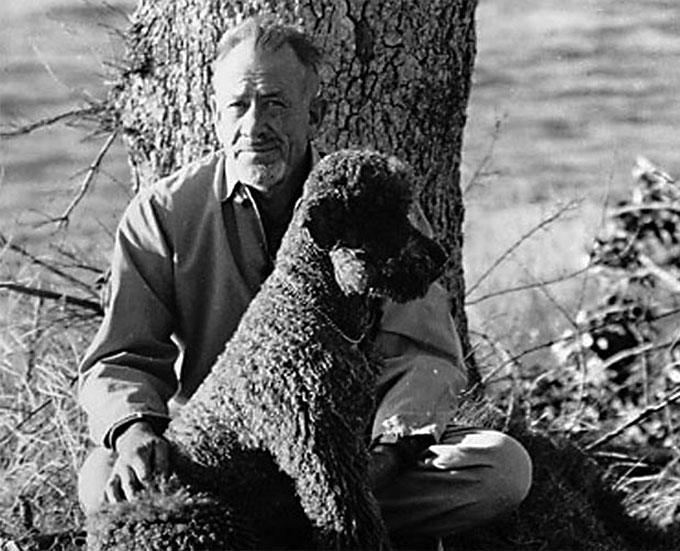

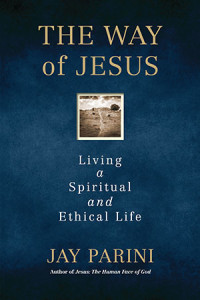

John Steinbeck studied Pilgrim’s Progress at his mother’s knee. Literally. John Bunyon’s allegory of sin and salvation was still family reading when Olive Steinbeck taught her pre-school son the alphabet 100 years ago and home libraries like the Steinbecks’ had books like Pilgrim’s Progress, so essential to Christian living that they were read aloud at family gatherings like the Bible. Like his father, John Steinbeck was often depressed about life, and Bunyon’s Slough of Despond colored his dark view of home town Salinas, a place of sloughs in both senses of Bunyon’s word—“swampy” and “characterized by lack of progress.” Like his mother, he had conflicting views about religion, “a curious mixture [for her, he said] of Irish fairies and an Old Testament Jehovah.” Her parents were frontier Calvinists, but she sent her son to the Episcopal church, where he stayed, nominally, until he died. He told his physician that he didn’t believe in an afterlife, but he wanted an Episcopal church funeral anyway and his fiction is full of religion gleaned from books he read in childhood—the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress—and mined for material in books still read today. Fortunately for readers without grounding in Steinbeck’s religion, Steinbeck’s biographer Jay Parini (in photo) has provided a Pilgrim’s Progress for the post-Christian century in The Way of Jesus, a spiritual autobiography by a gifted writer that also serves as a reader’s guide to Christianity in the spirit of Steinbeck’s fiction—progressive, companionable, and inviting participation.

The Way of Jesus: A Better Way to Understand Belief

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

Like John Steinbeck, Jay Parini found refuge in the Episcopal church from the fundamentalism of puritanical forebears. Like William Faulkner and Gore Vidal, authors whose lives he chronicled after writing about Steinbeck, Parini is a working novelist with a foot in the film world and—like Robert Frost, another subject—a people’s poet with a Vermonter’s view of America. He teaches creative writing at Middlebury College, and The Way of Jesus is a teaching book with all the traits of a well-taught course. A second-semester sequel to Parini’s life of Jesus with a literary approach to scripture and belief, it explores the poetry of T.S. Eliot and the aggregation of writings we call the Bible with equal agility. Designed for readers without special knowledge, its explanation of esoteric topics like Christian liturgy, Calvinist theology, and the church year—features of Steinbeck’s fiction from Tortilla Flat to The Winter of Our Discontent—is abundantly clear and courteous to newcomers. The ease and efficiency will appeal to students, and the extra equipment, including source documentation, will please their professors. Happiest of all will be fans of literature (if not religion) who love somebody else’s story when it involves them and invites action, like Steinbeck at this best.

John Steinbeck’s Warning in Playboy about Donald Trump

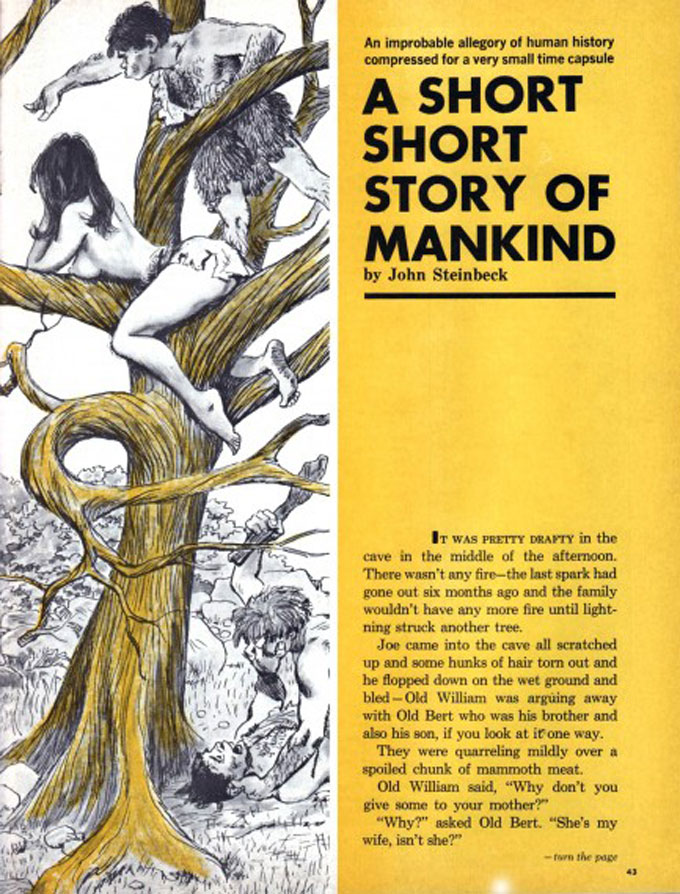

The long relationship between Playboy magazine and Donald Trump, America’s playboy-in-chief, is old news. But the recent death of Hugh Hefner unearthed some surprising Playboy connections, including a list of major authors—among them John Steinbeck—who wrote for the serious men’s magazine that paid well and reached readers otherwise untouched by serious literature. In light of our president’s tweets and threats to bomb America’s enemies back to the Stone Age, Steinbeck’s satirical “Short Short Story of Mankind,” first published in the April 1957 issue of Playboy, has a message as relevant today as it was 60 years ago, when the golf-loving Dwight Eisenhower was president and the Cold War was on in earnest.

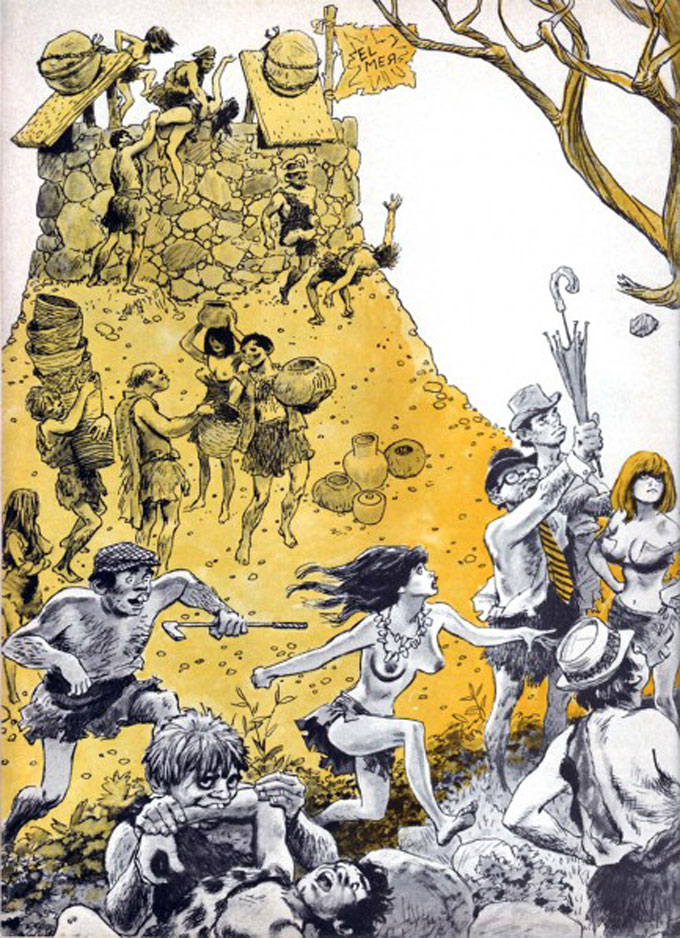

An allegory in the style of Mark Twain, Steinbeck’s account of human progress from savagery to civilization has a cartoon quality picked up by the illustrator for Adam, which republished Steinbeck’s Playboy piece in 1966 (images above and below). But like the “poisoned cream puff” of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row fiction, the mirth of “A Short Short Story of Mankind” is meant to be sobering. At every step, Steinbeck suggests, our progress as a species has faced resistance from a constant and terrifying tribal stupidity which, unchallenged, would lead to our extinction. “It’d be kind of silly if we killed our selves off after all this time,” he concludes. “If we do, we’re stupider than the cave people and I don’t think we are. I think we’re just exactly as stupid and that’s pretty bright in the long run.”

To my knowledge “A Short Short Story of Mankind” has never been anthologized, but it’s time it was. Living in the daily shadow of Donald Trump’s presidency, we need its dark warning and its ray of hope, the somber and uplifting counterpoint that echoes Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech and later writing. Today, six decades after Playboy magazine published John Steinbeck for the first and only time, it’s useful to remember that the author died a month after the election of Richard Nixon, whose dishonesty and demagoguery he deeply distrusted. It’s easy enough to imagine what he’d have to say about Donald Trump if he were still alive. The warning he’d have for a nation under Trump is implicit in the imagery and tone of his Cold War admonition to America under Eisenhower—an incurious president who also preferred golf but, unlike Trump, read the occasional book and avoided Stone Age rhetoric. Read the piece and judge for yourself.

Grammar-Check Your Blog Post About John Steinbeck

Though he occasionally misused or misspelled words, John Steinbeck wrote to be understood, often revising sentences, paragraphs, and whole chapters before publishing. Unfortunately, blog posts written about Steinbeck for online magazines, ostensibly with grammar-checking editors, frequently confuse readers with sentences so ill-considered that their meaning is unclear or absent. Recent examples of both errors in online writing about Steinbeck’s greatest fiction can be found in a pair of blog posts published by two online magazines that, except for sectarianism and under-editing, couldn’t be less alike.

How Did The Forward Get John Steinbeck So Wrong?

The first post in question is by Aviya Kushner, the so-called language columnist of The Forward, a respected Jewish publication started in New York five years before Steinbeck was born. The “news flash from the distant land of real news” on offer in Kushner’s May 8 blog post—“How Did John Steinbeck and an Obama Staffer Get the Bible So Wrong?”—is the misspelling of timshol in East of Eden, old news to Steinbeck fans of all faiths or no faith at all. Kushner’s charge—that Steinbeck’s spelling error was an offense against language, culture, and morality—is undermined by her syntax. “It comes down to caring about language,” she writes in conclusion, “and insisting that words have meaning, which is, frankly, a hot contemporary topic that is not just political but also moral.” Ouch and double ouch.

Faith Is No Excuse When Blog Posts Make No Sense

The second example of online magazines writing badly about John Steinbeck comes from Pantheon, a site that bills itself as “a home for godly good writing,” apparently without irony. “Dreaming of Steinbeck’s Country”—the May 6 blog post by a self-identified minister named James Ford—means well but also proves that sententious praise, like captious criticism, collapses when style fails subject in sentences describing Steinbeck. “I consider the Grapes of Wrath [sic] one of the great novels of our American heritage,” writes Ford. “Currents of spirituality and spiritual quest together with a progressive if increasingly that agnostic form of Christianity feature prominently in Steinbeck’s writings. And no doubt it informs his masterwork the Grapes of Wrath.” [Sic] and [sic] again.

Is Your Piece Ready to Publish, or Does It Escape?

The lesson to be learned from this week’s examples of bad online writing? When blogging about John Steinbeck, take time to spell- and syntax- and grammar-check before posting. Online magazines have editors, but contributed posts are like the morning newspaper in Florida whose editor I once overheard describe this way: “Our paper isn’t published. It escapes.” Websites with a sectarian purpose, like The Forward and Pantheon, often make the mistake of allowing sentiment to overwhelm sense when publishing blog posts by sincere writers with a pro or con ax to grind. Steinbeck agonized over The Grapes of Wrath. East of Eden took years to write. Travels with Charley didn’t, and it shows. Is taking time to self-edit when writing about John Steinbeck for any website, secular or religious, asking too much?

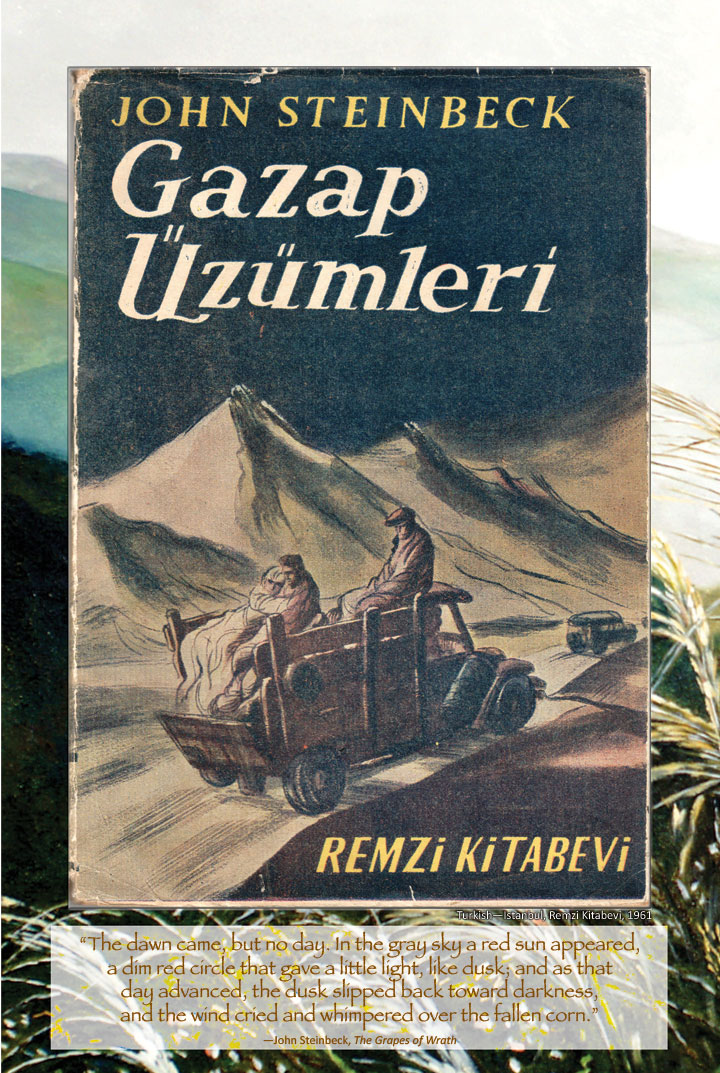

John Steinbeck, Islamic Religion, and the Globalism Of The Grapes of Wrath

John Steinbeck grew up in the Episcopal Church during an era when religion, like politics, tended to be insular. But parochial thinking never suited Steinbeck, a freethinker who practiced tolerance, traveled widely, and employed images and ideas from other faiths in his writing. Not surprisingly, Chaker Mohamed Ben Ali finds echoes of Islamic religion in The Grapes of Wrath, the novel that continues to attract attention to Steinbeck’s broad-minded values and ecumenical vision. A teacher in Algeria, Chaker Mohamed Ben Ali delivered his paper on Islam in the The Grapes of Wrath (written in collaboration with Salah Eddine Merouani) during the conference on Steinbeck’s internationalism held at San Jose State University in May. Posting his video presentation now seems especially appropriate in the context of current world events. It is a timely reminder that John Steinbeck’s global perspective is more relevant than ever, and it includes a helpful discussion about how to broadcast conference papers, like this one, to an online international audience.—Ed.

East of Eden Comes Alive at Brigham Young University

The information systems professor who heads the entrepreneurship program at Brigham Young University’s Marriott School of Business probably isn’t the first person who comes to mind when thinking about how to explain Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden to an academic audience. But that’s exactly what Steve Liddle—a California native who first read The Grapes of Wrath as a boy—brought off brilliantly in a stirring speech about free will and personal responsibility to Brigham Young University faculty and students on May 3. Non-members of the Mormon Church, with which the Provo, Utah university is affiliated, might consider Latter-Day Saints (the accurate term for Mormons) too conservative for Steinbeck, but Steve Liddle explains timshel better than anyone we’ve heard anywhere. Listen to the address at Brigham Young University’s podcast site to learn how. (To get to the East of Eden part quickly, advance the podcast dial to 20 minutes. But Liddle’s full speech is inspiring, even for non-Mormons.)

The information systems professor who heads the entrepreneurship program at Brigham Young University’s Marriott School of Business probably isn’t the first person who comes to mind when thinking about how to explain Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden to an academic audience. But that’s exactly what Steve Liddle—a California native who first read The Grapes of Wrath as a boy—brought off brilliantly in a stirring speech about free will and personal responsibility to Brigham Young University faculty and students on May 3. Non-members of the Mormon Church, with which the Provo, Utah university is affiliated, might consider Latter-Day Saints (the accurate term for Mormons) too conservative for Steinbeck, but Steve Liddle explains timshel better than anyone we’ve heard anywhere. Listen to the address at Brigham Young University’s podcast site to learn how. (To get to the East of Eden part quickly, advance the podcast dial to 20 minutes. But Liddle’s full speech is inspiring, even for non-Mormons.)

Pope Francis, John Steinbeck, and an Act of Grace in London, England

The historic visit to America by Pope Francis, which included the canonization of the Spanish-California missionary Junipero Serra, made some right-wing Catholics in Washington angry, though it would have pleased John Steinbeck, a politically progressive Episcopalian with Catholic sympathies. The pope’s call for justice, mercy, and kindness to strangers in his address to Congress inspired the editor in chief of Steinbeck Review to write about her experience with grace during a trip she took with her husband to a city John Steinbeck experienced as a welcome guest in times of war and peace: London, England.—Ed.

In “Republicans Could Have a Pope Problem,” a syndicated column about Pope Francis’s recent visit published in the September 25, 2015, Birmingham, Alabama News, the journalist Margaret Carlson writes, “Pope Francis suffused Washington with what Catholics would call grace and what everyone else—for the crowds aren’t just believers—would call pure, almost childlike happiness.” Concluding that “this is what goodness looks like,” she predicts that certain politicians and vested interests may find the Pope’s message to America—one that is so very much like John Steinbeck’s moral stance in The Grapes of Wrath—problematic, even meddling. Notes Carlson of the Pope’s emphasis on immigration reform, economic justice, and ecological awareness during his speech to Congress:

My God, he’s questioning unfettered capitalism and the worship of wealth. . . . “The son of an immigrant family” said we should welcome those who come to the U.S. Such effrontery. With Republicans watching from lawn chairs, he said that those at the top of the economic heap have a duty to fight climate change on behalf of the millions left behind by the global economic system. “Climate change is a problem which can no longer be left to a future generation,” he said. Before he leaves, he could very well call for raising taxes.

John Steinbeck would have loved this pope, who chose the occasion of his American visit to canonize Junipero Serra, the 18th century Franciscan missionary to Spanish California. Like Steinbeck, Pope Francis has a compassionate heart for the dispossessed, a dim view of ostentatious consumerism, and an abiding sense of our intimate connection to Mother Earth and the interrelatedness of all things that Casy proclaims in The Grapes of Wrath. Like Francis, John Steinbeck’s novel challenges the status quo, holds out hope for change despite the odds, and calls for love in a world threatened equally by the hatred of enemies and the complacency of friends and allies.

John Steinbeck would have loved this pope, who chose the occasion of his American visit to canonize Junipero Serra, the 18th century Franciscan missionary to Spanish California.

Although not a Catholic, California’s greatest writer was a political progressive who was friendly to Catholicism and saved his criticism of organized religion for the narrow-minded and the hypocritical—characteristics of conservative Catholic politicians such as Senator Marco Rubio, to whom Carlson refers in her article. “As for Rubio,” she suggests, “perhaps the Pope will persuade him to follow Christ’s teachings and not his most conservative followers and donors. Miracles do happen.”

Although not a Catholic, California’s greatest writer was a political progressive who was friendly to Catholicism and saved his criticism of organized religion for the narrow-minded and the hypocritical.

An Anglican who loved to travel, John Steinbeck particularly liked London, England, where I experienced my own minor miracle on the last leg of the European trip my husband Charlie and I took shortly before Pope Francis came to the United States. The date was September 20, the night before our return flight to Atlanta; the place, London’s Mayfair Millennial Hotel. As we finished dessert in the hotel dining room and prepared to pay our bill, my husband reached for his wallet. It wasn’t in his pocket. We knew instantly how someone had taken it earlier in the day—giving me a shove and stealing Charlie’s billfold while we were distracted. Far from home and facing the prospect of having to cancel all of our credit cards, we felt violated, desolate, and a bit desperate.

I experienced my own minor miracle on the last leg of the European trip my husband Charlie and I took shortly before Pope Francis came to the United States.

Thirty minutes before we were scheduled to check out the next morning, our concierge phoned our room with welcome news: “A lady has called to report that she has your billfold. It is being held for you at a hotel not too far away, and you may pick it up any time.” When we arrived at the hotel, we found Charlie’s wallet intact—his credit cards, his driver’s license, even his cash. Details of what happened to the billfold—it had been found by a Good Samaritan on a street far from Regent’s Park, where we had spent the previous afternoon—remained a mystery. As we left for the airport to fly home, everyone at the hotel desk was smiling, agreeing that this warmhearted act of grace was a “London miracle.”

As we left for the airport to fly home, everyone at the hotel desk was smiling, agreeing that this warmhearted act of grace was a ‘London miracle.’

The incident in England made an impact on us that John Steinbeck would have understood and appreciated. Like the presence of Pope Francis in the United States, it restored our belief in the possibility of goodness and honesty, decency and kindness. As Margaret Carlson notes, “Miracles do happen.”

The incident in England made an impact on us that John Steinbeck would have understood and appreciated.

Pope Francis is calling for miracles today, and characters in Steinbeck’s fiction like Ma Joad attest to their possibility. Perhaps we shall see more “miracles” in the future. I hope so, because our own fate and that of the earth we inhabit depend on them. Perhaps “good will,” “the common good,” and sustaining “Mother Earth” will become practical possibilities rather than impossible dreams. Perhaps the impression left by Pope Francis will endure, making life better for the planet we inhabit and for the strangers in our midst, whether on our border or on a side street in London, England.

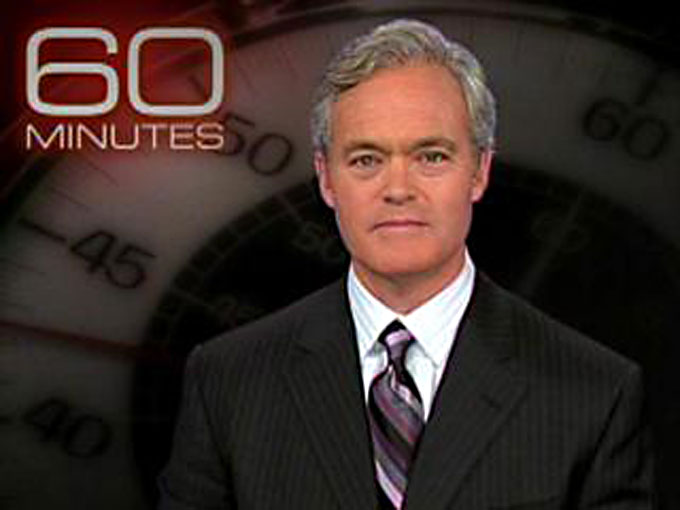

Is Pope Francis a Fan of John Steinbeck? CBS News Reporter Scott Pelley Gives The Popular Pope a Copy of The Grapes of Wrath

Has Pope Francis read John Steinbeck? CBS News reporter Scott Pelley, a big fan of both men, thinks they have much in common in matters of justice, mercy, and conscience. (Barbara A. Heavilin, editor in chief of Steinbeck Review, agrees, relating the pope and the author’s shared hope for suffering humanity to an incident that occurred on a recent trip abroad.) During a 60 Minutes segment that aired on September 20, Scott Pelley previewed the pope’s historic visit to the United States, which included an address on Capitol Hill boycotted by three Catholic members of the Supreme Court’s conservative wing. Earlier, Pelley explained in a 60 Minutes Overtime interview why he handed Pope Francis an Italian edition of The Grapes of Wrath while on assignment in Rome in preparation for the segment. He said he was a descendant of displaced Dust Bowl victims who, like the “Okies” in The Grapes of Wrath, were refugees within their own country during the Great Depression. That connection, he explained, made John Steinbeck and Pope Francis more than news for him. It made them relevant.

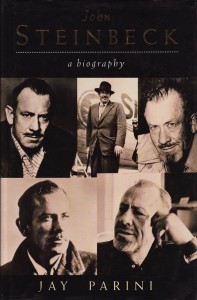

John Steinbeck-Robert Frost Biographer Jay Parini Writes New Life of Jesus Christ

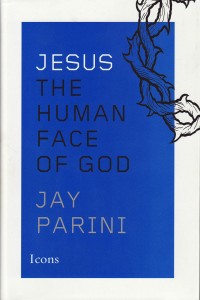

What does Jesus Christ—or John Steinbeck or Robert Frost—really mean to me? John Steinbeck: A Biography by the writer Jay Parini helped me understand why Steinbeck’s life and work spoke to me so powerfully when I first began reading Steinbeck’s books. Robert Frost is another favorite, and Parini—a professor of creative writing at Middlebury College—brought his fellow New England poet’s interior landscape into focus for me with Robert Frost: A Life, his second work of biography. A celebrated Middlebury College faculty member for more than 30 years, Parini has employed his enviable skills as a poet, novelist, and scholar to re-imagine the life of Jesus Christ—the greatest story of them all—in Jesus: The Human Face of God.

What does Jesus Christ—or John Steinbeck or Robert Frost—really mean to me? John Steinbeck: A Biography by the writer Jay Parini helped me understand why Steinbeck’s life and work spoke to me so powerfully when I first began reading Steinbeck’s books. Robert Frost is another favorite, and Parini—a professor of creative writing at Middlebury College—brought his fellow New England poet’s interior landscape into focus for me with Robert Frost: A Life, his second work of biography. A celebrated Middlebury College faculty member for more than 30 years, Parini has employed his enviable skills as a poet, novelist, and scholar to re-imagine the life of Jesus Christ—the greatest story of them all—in Jesus: The Human Face of God.

The new book represents a progression, not a departure, for Parini. John Steinbeck was a lifelong Episcopalian who considered Jesus Christ a moral genius, read and raided the Bible for his fiction, and once thought about writing the screenplay for a Jesus Christ biopic based on the gospels that was never made. Like Robert Frost, Steinbeck valued personal privacy and resisted dogmatic assertions of belief, so we’ll never know how his Christ would have fared on film. For that matter, what do we really know about the details of Jesus’ life from historic records? American writers before and since Steinbeck—including the late Duke University novelist and poet Reynolds Price—have rescripted the Man from Galilee with intriguing angles and uneven results. Now an inspired and imaginative writer from Middlebury College—one of America’s oldest and finest schools—has succeeded where others failed.

Jay Parini: The Man from Middlebury College

Like young John Steinbeck growing up in what became Steinbeck Country, Jay Parini is active in his Episcopal church, located not far from Middlebury College in Robert Frost Country, the home turf of Steinbeck’s New England grandparents. Unlike Steinbeck, Parini is fluent in New Testament Greek; like the author, he knows his Bible and his theology and has explored other traditions—Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism—in depth. But I suspect that none of that is unusual around Middlebury College, long a center of language and cultural studies without equal for its size. Resurrecting Jesus Christ from the tomb of time as Parini has done requires a tool more powerful than scholarship, even the industrial-strength form found in the halls of Middlebury College. Re-mythologizing (Parini’s term) requires an eye for the unseen, an ear for the unknowable, and a writer’s way with words. After three decades of practice writing for mainstream readers, Parini possesses these gifts in abundance. His first collection of poems appeared in 1982. His most recent novel was published in 2010. Four years ago his third novel—The Last Station—became an Academy Award-nominated movie.

Like young John Steinbeck growing up in what became Steinbeck Country, Jay Parini is active in his Episcopal church, located not far from Middlebury College in Robert Frost Country, the home turf of Steinbeck’s New England grandparents. Unlike Steinbeck, Parini is fluent in New Testament Greek; like the author, he knows his Bible and his theology and has explored other traditions—Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism—in depth. But I suspect that none of that is unusual around Middlebury College, long a center of language and cultural studies without equal for its size. Resurrecting Jesus Christ from the tomb of time as Parini has done requires a tool more powerful than scholarship, even the industrial-strength form found in the halls of Middlebury College. Re-mythologizing (Parini’s term) requires an eye for the unseen, an ear for the unknowable, and a writer’s way with words. After three decades of practice writing for mainstream readers, Parini possesses these gifts in abundance. His first collection of poems appeared in 1982. His most recent novel was published in 2010. Four years ago his third novel—The Last Station—became an Academy Award-nominated movie.

Resurrecting Jesus Christ from the tomb of time as Parini has done requires a tool more powerful than scholarship . . . .

Parini’s first venture beyond poetry was his life of John Steinbeck, released in 1994 by Steinbeck’s English publisher (cover image below) and published in the USA in 1995. It was followed by two more literary lives, those of Robert Frost (2000) and William Faulkner (2004), making Jesus Christ Parini’s fourth act biography, a challenging art-form that doesn’t always produce miracles. Among the academically inclined, Parini’s The Art of Teaching (2005) and Why Poetry Matters (2008), plus a host of anthologies, have attracted acclaim. Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America (2008) remains a vade mecum for those exploring the topography of American fiction for the first time. Film adaptations of a pair of Parini novels—Benjamin’s Crossing (1997) and The Passages of H.M. (2010)—are underway. Galliano’s Ghost, another novel, is in progress. So is Conversations with Jay Parini, a University of Mississippi Press publication edited by Michael Lackey. In case you’re counting, that puts him just about where John Steinbeck was at a comparable point in his dizzingly diverse career as a writer.

John Steinbeck: A Life

Like Steinbeck, Parini has his critics. I learned this when I answered a Steinbeck scholar’s recent query. What’s your favorite Steinbeck biography? I replied that I still loved the first one I ever read—John Steinbeck: A Biography. If looks could kill, Parini’s book and I both died that day. Had I spoken heresy? If so, I guess I understand. I too have found reason to quibble with minor points in Parini’s life, published years after another biographer’s much longer book, in my recent research into Steinbeck’s religious roots. But—pardon me—Jesus Christ! Do you want good footnotes or great style? Better than any other biographer I know of John Steinbeck or Robert Frost, Parini sees his subject steadily and sees him whole, telling a creative writer’s story as only a creative writer can. If you’re curious about the time the particular author you’re studying went to the bathroom in his publisher’s office on a given day, be my guest—find the longest biography you can. If you want to know how he recalibrated a certain character, re-imagined a significant scene, or overcame writer’s block to meet a deadline, ask another writer. For John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, Jay Parini more than meets this taste test.

Like Steinbeck, Parini has his critics. I learned this when I answered a Steinbeck scholar’s recent query. What’s your favorite Steinbeck biography? I replied that I still loved the first one I ever read—John Steinbeck: A Biography. If looks could kill, Parini’s book and I both died that day. Had I spoken heresy? If so, I guess I understand. I too have found reason to quibble with minor points in Parini’s life, published years after another biographer’s much longer book, in my recent research into Steinbeck’s religious roots. But—pardon me—Jesus Christ! Do you want good footnotes or great style? Better than any other biographer I know of John Steinbeck or Robert Frost, Parini sees his subject steadily and sees him whole, telling a creative writer’s story as only a creative writer can. If you’re curious about the time the particular author you’re studying went to the bathroom in his publisher’s office on a given day, be my guest—find the longest biography you can. If you want to know how he recalibrated a certain character, re-imagined a significant scene, or overcame writer’s block to meet a deadline, ask another writer. For John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, Jay Parini more than meets this taste test.

Do you want good footnotes or great style?. . . For John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, Jay Parini more than meets this taste test.

Like Steinbeck’s fiction, Parini’s biography of John Steinbeck continues to be popular with readers who are not writing dissertations. I recommend it to anyone interested in learning how Steinbeck developed his craft and overcame his problems. I reread it so often it because it flows so well—unimpeded by anxious over-annotation, syntactical complexity, or current critical cant. Parini’s life of Robert Frost—a natural next subject for a Middlebury College poet-biographer—has the same value for non-natives entering Robert Frost Country for the first time. I’m a Southerner, but I’ll confess that I haven’t read Parini’s biography of William Faulkner, John Steinbeck’s fellow-Nobel Laureate and sometime competitor. My excuse? In graduate school ions ago I studied Faulkner under a meticulous biographer who read from his notes for the prodigious life of Faulkner he was writing. Information without imagination. Not Jay Parini’s problem.

Thinking about Jesus Christ with John Steinbeck in Mind

We can’t know with confidence how Steinbeck’s film Christ would have acted or even looked. But the Jesus brought to fresh life in Parini’s new biography seems just like one of us, only more so. I kept thinking of Steinbeck as I read the book. Though Steinbeck claimed to have no religion (not that odd for an Episcopalian), he disliked reading scripture in any version other than King James, which he knew like, well, the bible. In his new narrative Parini sticks to King James for big stuff like the Beatitudes. But for most of the passages he quotes from or about Christ he provides his own translation—immediate, clear, compelling—in fulfillment of his promise to lift Jesus from the pile of dogma, myth, and demythologizing that have smothered the Christ story. Along the way he quotes other poets, cites other scholars, and acknowledges other teachers at Middlebury College, all without losing momentum or focus for a second. His Jesus Christ is a living teacher speaking in an existential now with something to say to all people. As a believer Parini is passionate about his subject. As a teacher he is careful about his approach. The result? Jesus: The Human Face of God is like a well-taught introductory course in a class of non-majors. No declared religion is required to participate, and doubt is more than welcome. In fact it’s advised.

We can’t know with confidence how Steinbeck’s film Christ would have acted or even looked. But the Jesus brought to fresh life in Parini’s new biography seems just like one of us, only more so. I kept thinking of Steinbeck as I read the book. Though Steinbeck claimed to have no religion (not that odd for an Episcopalian), he disliked reading scripture in any version other than King James, which he knew like, well, the bible. In his new narrative Parini sticks to King James for big stuff like the Beatitudes. But for most of the passages he quotes from or about Christ he provides his own translation—immediate, clear, compelling—in fulfillment of his promise to lift Jesus from the pile of dogma, myth, and demythologizing that have smothered the Christ story. Along the way he quotes other poets, cites other scholars, and acknowledges other teachers at Middlebury College, all without losing momentum or focus for a second. His Jesus Christ is a living teacher speaking in an existential now with something to say to all people. As a believer Parini is passionate about his subject. As a teacher he is careful about his approach. The result? Jesus: The Human Face of God is like a well-taught introductory course in a class of non-majors. No declared religion is required to participate, and doubt is more than welcome. In fact it’s advised.

His Jesus Christ is a living teacher speaking in an existential now with something to say to all people.

The unsmiling Jesus Christ depicted in classic Orthodox iconography (as in the cover image below) seems distant, two-dimensional, hard to embrace, at least for me. Parini’s Jesus, like John Steinbeck’s Ma Joad, is bigger than life but also fully formed, and in the end all-forgiving. The confusing nomenclature of the Bible presents another obstacle to understanding for many. Since I was a kid memorizing the books of the Bible for Sunday school to the time I took the required Old and New Testament courses (both excellent) in college, I’ve felt foggy about biblical names of greater complexity than Paul or Peter and theological ideas more complicated than I Am That I Am. Parini cleared some air in my head.

Parini’s Jesus, like John Steinbeck’s Ma Joad, is also bigger than life but fully formed, and in the end all-forgiving.

For example, I could never keep my Sadducees and my Pharisees straight. No longer! Parini traces the origin of the Sadducees to Saduc, “a legendary high priest from the time of King David,” and describes the group as an easygoing, cultured elite who looked down on their neighbors the Pharisees, seriously doubted the doctrine of bodily resurrection, and deeply enjoyed hobnobbing with foreigners: Episcopalians! The Pharisees? Puritanical, parochial, sure of their salvation—Presbyterians! That confusing half-human, half-divine thing about the true nature of Jesus Christ? Aha! It started with the Romans, maybe earlier. Virgin Birth? Greek and Persian, not Hebrew. Satan? Definitely Hebrew—ha-Satan. Marriage? Jesus Christ was single, but he loved women, knew how to kiss, and produced wine at a wedding over the objections of his mother, a miracle that would have moved a drinker like Steinbeck deeply.

Jesus Christ was single, but he loved women, knew how to kiss, and produced wine at a wedding over the objections of his mother, a miracle that would have moved a drinker like Steinbeck deeply.

In fact, Parini’s Jesus Christ embodies John Steinbeck’s most enviable qualities as a writer and his most admirable aspirations as a man. Listen:

You talked to women without troubling over gender rules. You confronted people about their past lives, their current situation. You didn’t worry about their racial or political origins but sought to bring them into a state of reconciliation with God, a condition of atonement that would fill them with “living water” that reached beyond physical thirst.

Parini’s Jesus Christ loves water, enjoys boats, and is at ultimate ease around fisherman, three constants in John Steinbeck’s sea-sotted life. Jesus is even friendly to tax-collectors (Steinbeck’s father was the county treasurer) and—like Steinbeck—he hated poverty, despised cruelty, and always stuck up for the underdog without starting a war. As Steinbeck, so Jesus: sin is Karma, and it starts inside: “Forgiveness leads to godly behavior”— “anger leads to murderous behavior.” Like Cain and Abel in East of Eden, Parini’s Jesus “takes his listeners back to the origins of murder, anger itself.” Like John Steinbeck in his time, Parini’s Jesus considers affluence a cause of poverty, advising “insane generosity, especially if you love it.” More: “annoy, even outrage, the elite classes. . . .” That’s the mantra Middlebury College had back in my day. I hope it is now. It was certainly Steinbeck’s, starting at Stanford.

Both Jesus and John Made Their Own Myth

Like John Steinbeck, Parini’s Jesus Christ is the maker of his own myth—a slippery term of art in literature that Parini nails down as story. It’s the same meaning Steinbeck had in mind when he resisted the idea of his life story being written while he was still alive, preferring instead to create his own life myth—and not just in novels. So, in his way, with Parini’s Jesus Christ: “One gets the sense that Jesus, knowing the plot of his own story, had arranged everything in advance.” Steinbeck was also skeptical of sudden revolution and instant redemption—much like Parini’s Jesus. Steinbeck on history: Man’s war is with himself. Progress is certain but slow. Peace starts with you. Parini on Christ:

Like John Steinbeck, Parini’s Jesus Christ is the maker of his own myth—a slippery term of art in literature that Parini nails down as story. It’s the same meaning Steinbeck had in mind when he resisted the idea of his life story being written while he was still alive, preferring instead to create his own life myth—and not just in novels. So, in his way, with Parini’s Jesus Christ: “One gets the sense that Jesus, knowing the plot of his own story, had arranged everything in advance.” Steinbeck was also skeptical of sudden revolution and instant redemption—much like Parini’s Jesus. Steinbeck on history: Man’s war is with himself. Progress is certain but slow. Peace starts with you. Parini on Christ:

Recognition takes time, becoming in fact a process of uncovering, what I often refer to in this book as the gradually realizing kingdom: an awareness that grows deeper and more complex, more thrilling, as it evolves.

Parini’s life of Jesus Christ, like the fiction of John Steinbeck, engaged me as a participant, not on the sidelines. Occasionally I got so involved I even wanted to add things, as Steinbeck urges us to do when we participate in his stories and continue them in our lives, where they have their true ending. One example must suffice. Late in the his Jesus story Parini pauses to reflect on the unrecognized irony—“lost on our ears now”—implicit in the name of the rebel Bar-abbas, “son of the father,” freed by Pilate in place of Jesus. How I hoped Parini w0uld stop to savor another, deeper irony, spoken by Christ himself to the Sanhedrin shortly before he’s delivered to the Romans: “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.” Hear what Jesus is saying? Your assumptions are all wrong. Nothing is Caesar’s. Everything belongs to God.

This life reminds this reader why Jesus Christ, like John Steinbeck and Robert Frost, has found an ideal biographer in the churchgoing poet-novelist from progressive Middlebury College. Like Jay Parini, John Steinbeck was a socially-conscious Episcopalian storyteller writing for the multitude. Like Robert Frost, Middlebury College sprang from the soil and salt of Steinbeck’s paternal New England, where Parini makes his home. And Jesus Christ loved us all. This book tells me that Jay does too.

Michael Meyer and the Bridge Between Literary Criticism and the Bible

As a Baptist minister in England for 40 years, my attachment to Steinbeck came rather later in life. Over time, literature (particularly drama) became increasingly important in my ministry, to my writing and preaching on the Bible, and in my development of Bible study tools. Steinbeck finally clicked for me in the late 1990s when I read The Grapes of Wrath. My interest in the author ultimately led to writing literary criticism and forming friendships with American scholars. Among them was the late Michael Meyer, whose death in 2011 deeply saddened the international Steinbeck community.

As a Baptist minister in England for 40 years, my attachment to Steinbeck came rather later in life. Over time, literature (particularly drama) became increasingly important in my ministry, to my writing and preaching on the Bible, and in my development of Bible study tools. Steinbeck finally clicked for me in the late 1990s when I read The Grapes of Wrath. My interest in the author ultimately led to writing literary criticism and forming friendships with American scholars. Among them was the late Michael Meyer, whose death in 2011 deeply saddened the international Steinbeck community.

A Bridge Between Bible Study Tools and Literary Criticism

Beyond Steinbeck’s numerous references to religion in The Grapes of Wrath, the book’s biblical and theological themes struck me as revealing much about the author’s life and character. In no way was he irreligious, I thought, and in many respects I found him running very close to Christianity as I understood it—though he might not thank me for saying so.

Knowing that the corpus of literary criticism about Steinbeck (like Bible study tools) is immense, I was only too aware of the hazards of digging in my spade as a writer in such well-trodden territory. My first ventures in Steinbeck literary criticism were occasional articles such as “Rumour of God” and “Steinbeck’s View of God.” The longer I thought about the gap that exists between literary criticism and biblical studies, however, the more clearly I realised that Steinbeck represents rich but neglected territory for biblical scholars, preachers, and publishers of Bible study tools. Unfortunately, my initial attempts to introduce these sources to Steinbeck met with little response. I also realised that much of the literary criticism produced on Steinbeck was equally neglectful of developments in biblical studies. Could Steinbeck become a bridge between the worlds of literary criticism, biblical scholarship, and Bible study tools? I thought so.

Thanks to my son (whose job at the time conveniently took him to California), I had the opportunity to do some digging on my own in Steinbeck’s native soil. Meeting Susan Shillinglaw at San Jose State University and her colleagues in Steinbeck’s home town of Salinas led me to write my first article for the American journal Steinbeck Studies, “Did Steinbeck Know Wheeler Robinson?,” as well to an invitation to present my paper “Did Steinbeck Have a Suffering Servant?” as part of the Steinbeck Centennial Conference held at Hofstra University.

Meeting Michael Meyer, a Master of Literary Criticism

Among the Steinbeck scholars I met at Hofstra in 2002 was Michael Meyer, a professor at DePaul University and an acknowledged master of Steinbeck literary criticism. We shared a taxi from the airport to the campus, and he asked about my background. When I told him that my major interest was biblical studies, particularly the Old Testament, he said that he was a student of the Old Testament as well, and a bond was struck.

In due course Mike asked me to contribute to a new collection of literary criticism he was preparing on The Grapes of Wrath. This invitation led to my article “Biblical Wilderness in The Grapes of Wrath,” later published in The Grapes of Wrath: A Re-consideration. Then, following a brief walk in the byways for a similar contribution to Mike’s collection of literary criticism on Harper Lee—To Kill a Mocking Bird: New Essays—Mike invited me to contribute to a collection of literary criticism on East of Eden. Recently published as East of Eden: New and Recent Essays, the anthology includes my article “A Steinbeck Midrash on Genesis 4: 7.” Mike’s untimely death interrupted the process of publication, which was completed by Henry Veggian of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. When Mike died, I was nine-tenths of my way through another article of literary criticism that Mike had requested on the subject of Steinbeck and Morte d’Arthur.

Thanks to Mike, the bridge between the formerly alien territories of literary criticism and biblical scholarship, theology, and Bible study tools seems firmer than before. Mike was more than a master of Steinbeck literary criticism. He was also a fine editor, warm friend, and encourager of those—like me—who feel increasingly comfortable in both worlds.