“Shattering Illusions of a Benign World”—an April 17, 2020 Wall Street Journal book review by the writer Robert D. Kaplan—compares the Dust Bowl disaster depicted by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath with the contemporary calamity of COVID-19. Citing Steinbeck’s 1939 novel as “a powerful, inspiring story of human resilience in the face of unfathomable hardship” with a hard-but-hopeful lesson for the age of COVID-19, Kaplan praises Steinbeck’s masterpiece as “a book about how the natural environment seals human destiny, even while fathoming human character as has rarely been done in literature.” Other fans in high places are drawing similar conclusions. An April 25, 2020 AZcentral.com opinion piece by USA Today contributor Edward A. Pouzar—“Manhattan is the inferno of coronavirus”—finds encouragement for discouraged New Yorkers in “the unbelievable Joad hope which helped the family move forward each day” in their flight from Dust Bowl Oklahoma to Depression-era California. Taken together, the two articles are another reminder of John Steinbeck’s remarkable reputation for relevance beyond the classroom, particularly with readers from the worlds of business and politics. Kaplan, a former foreign affairs reporter for The Atlantic and the author of 19 books of travel and political analysis, is a managing director at the Eurasia Group, a global consulting business that evaluates political risk for private clients. Pouzar is director of risk management for Deloitte’s consulting business in New York, the city Steinbeck once described as the only place he could live after California.

Is Reading Steinbeck an Antidote to Donald Trump?

A rotten egg incubated by reality television and hatched by retrograde thinking about women and the world, the presidency of Donald Trump is creating anxiety, fear, and a growing sense among progressives that an American psycho now occupies the White House. Many, like me, are turning to John Steinbeck for understanding. But that consolation has its limits.

The presidency of Donald Trump is creating anxiety, fear, and a growing sense among progressives that an American psycho now occupies the White House.

As Francis Cline observed recently in The New York Times, one positive result of the groundswell of bad feeling about Trump is that “[q]uality reading has become an angst-driven upside.” Anxious Americans yearning to feel at home in their own country have a rekindled interest in exploring their identity through great literature. “Headlines from the Trump White House,” Cline notes, “keep feeding a reader’s need for fresh escape” and “alternate facts,” when “presented by a literary truthteller” like John Steinbeck, are “a welcome antidote to the alarming versions of reality generated by President Donald Trump.”

‘Alternate facts,’ when ‘presented by a literary truthteller’ like John Steinbeck, are ‘a welcome antidote to the alarming versions of reality generated by President Donald Trump.’

The literary tonic recommended by Cline may or may not have the power to clear the morning-after pall of Trump-facts and Trump-schisms (the two sometimes interchangeable) afflicting our panicked public dialogue, our beleaguered press, and, for those as apprehensive as I am, the American-psycho recesses of our collective mind. Perhaps counter-intuitively, his prescription for mental wellness includes works by a group of novelists with a far darker worldview than that of Steinbeck, who felt an obligation to his readers to remain optimistic about the future whenever possible. The writers mentioned by Cline include Sinclair Lewis (It Can’t Happen Here), George Orwell (1984), Aldous Huxley (Brave New World), William Faulkner (The Mansion), Jerzy Kosinski (Being There), Philip Roth (The Plot Against America), and Philip Dick (The Man In The High Castle). As an antidote to Donald Trump, they are bitter medicine. Is Steinbeck’s better?

The prescription for mental wellness includes works by a group of novelists with a far darker worldview than that of Steinbeck, who felt an obligation to his readers to remain optimistic about the future whenever possible.

As the Trump administration pushes plans to litter federally protected Indian land with pipelines (“black snakes”) that threaten to pollute the water used by millions of Americans, John Steinbeck’s writing about the dangers of environmental degradation seems more relevant, and more urgent, than ever. To mark the 100th anniversary of Steinbeck’s birth in 2002, the award-winning author and journalist Bil Gilbert wrote an insightful article on the subject for The Smithsonian entitled “Prince of Tides.” In it he notes that “Steinbeck’s powerful social realism is by no means his only claim to greatness. He has also significantly influenced the way we see and think about the environment, an accomplishment for which he seldom receives the recognition he deserves.”

But Steinbeck’s writing about the dangers of environmental degradation seems more relevant, and more urgent, than ever.

Judging from “The Literature of Environmental Crisis,” a course at New York University, Gilbert’s point about Steinbeck’s stature as an environmental writer of major consequence is now more generally accepted than he thinks. Studying what “it mean[s] for literature to engage with political and ethical concerns about the degradation of the environment” the class will read “such literary and environmental classics as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath” to “look at the way literature changes when it addresses unfolding environmental crisis.”

Judging from ‘The Literature of Environmental Crisis,’ a course at New York University, Steinbeck’s stature as an environmental writer of major consequence is now generally accepted.

“Before ‘ecology’ became a buzzword,” Gilbert adds, “John Steinbeck preached that man is related to the whole thing,” noting that Steinbeck’s holistic sermonizing about nature’s sanctity reached its peak in Sea of Cortez, the literary record of Steinbeck’s 1940 expedition to Baja California with his friend and collaborator Ed Ricketts, the ingenious marine biologist he later profiled in Log from the Sea of Cortez. In it Steinbeck seems to foresee how America’s precious national resources—and collective soul—could one day become susceptible to the manipulations of an amoral leader like Donald Trump:

There is a strange duality in the human which makes for an ethical paradox. We have definitions of good qualities and of bad; not changing things, but generally considered good and bad throughout the ages and throughout the species. Of the good, we think always of wisdom, tolerance, kindness, generosity, humility; and the qualities of cruelty, greed, self-interest, graspingness, and rapacity are universally considered undesirable. And yet in our structure of society, the so-called and considered good qualities are invariable concomitants of failure, while the bad ones are the cornerstones of success. A man – a viewing-point man – while he will nevertheless envy or admire the person who through possessing the bad qualities has succeeded economically and socially, and will hold in contempt that person whose good qualities have caused failure.

“Donald Trump has been in office for four days,” observed Michael Brune, the national director of the Sierra Club, “and he’s already proving to be the dangerous threat to our climate we feared he would be.” The executive actions taken by Trump in his first week as president (“I am, to a large extent, an environmentalist, I believe in it. But it’s out of control”) appear to fulfill Steinbeck’s prophecy about the triumph of self-interest over social good. That’s a hard pill to swallow for anyone who cares about the planet.

The executive actions taken by Trump in his first week as president appear to fulfill Steinbeck’s prophecy about the triumph of self-interest over social good. That’s a hard pill to swallow for anyone who cares about the planet.

Whether Trump becomes the kind of full-throttle fascist described in It Can’t Happen Here remains to be seen. Sinclair Lewis’s fantasy of a future fascist in the White House appeared the same year as Tortilla Flat, Steinbeck’s sunny ode to multiculturalism and the common man. Unfortunately, I’m not as optimistic about the American spirit as John Steinbeck felt obliged to be when he wrote that book more than 80 years ago. I’m afraid that the man occupying the high castle in Washington today is an American psycho with the capacity to do permanent harm, not only to the environment, but to the American soul Steinbeck celebrated in his greatest fiction.

Ed Ricketts, Aldo Leopold, And the Birth of the Modern Environmental Movement

A bright, breezy book timed for the 75th anniversary of Ricketts and Steinbeck’s famous expedition to the Sea of Cortez traces today’s environmental movement and the modern field of conservation biology to two prophets born ahead of their time, 10 years and 200 miles apart, more than a century ago. As Michael J. Lannoo dramatically demonstrates in Leopold’s Shack and Ricketts’s Lab: The Emergence of Environmentalism, Aldo Leopold and Ed Ricketts approached wildlife biology, marine biology, and the earth’s ecology in a whole new way, the result of intimate observation, original thinking, and lively conversation at Ricketts’s lab on Cannery Row and Leopold’s shack on reclaimed farmland in Wisconsin—apt metaphors for the sociable minds of two unconventional scientists whose parallel paths never crossed.

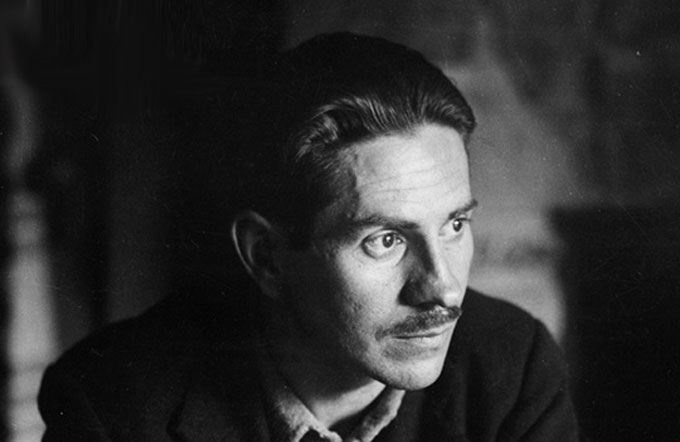

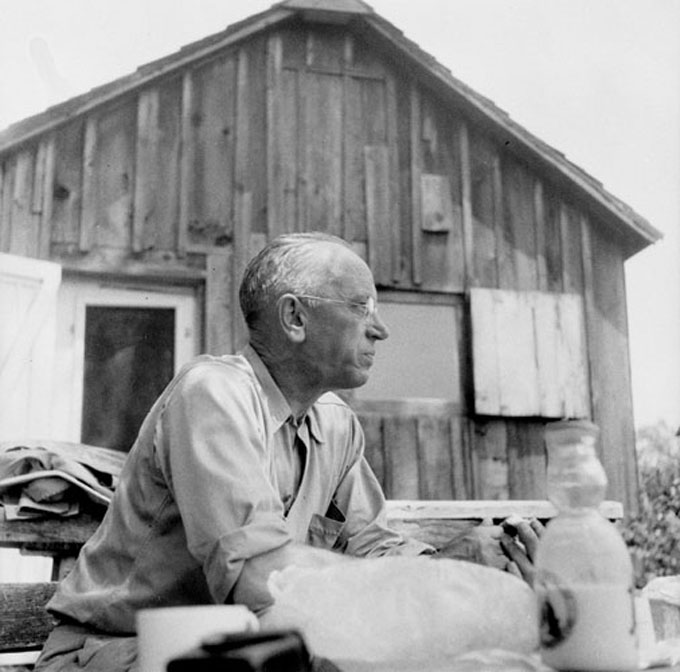

The story of Ricketts, marine biology, and the 1940 collecting expedition to the Sea of Cortez is familiar territory for Steinbeck fans and “Ed Heads,” the ardent admirers who consider Doc’s lab a shrine, like Lourdes. A less familiar narrative, equally fateful, was unfolding in the woods of Wisconsin during the same period, the 1930s and 40s, in the shack and mind of Aldo Leopold, the father of professional wildlife biology and author of Sand County Almanac (1949). Like Sea of Cortez, Leopold’s classic took time to gain steam; like Ricketts, Leopold died too soon to see his ideas change the course of science, land management, and the way we think.

Leopold died of a heart attack on the Wisconsin land he loved in 1948, months before the book that made him an environmental-movement hero was published. Two weeks later Ricketts was also dead, the result of injuries sustained when his car struck a train near his Cannery Row lab. Leopold, 10 years Ricketts’s senior, never met the transplanted Chicago native who made Cannery Row famous, in fiction and in fact. But Ricketts’s mystical thinking about marine biology eventually converged with Leopold’s ethic of wildlife biology to create the field of conservation biology and the holistic vision of today’s environmental movement, a benign way of living with nature minus the impulse to over-farm, over-fish, over-build, and over-populate. Like Steinbeck, Leopold was angered by urban sprawl and consumer waste. Like Steinbeck and Ricketts, he thought science was a saner faith than religion.

Ricketts’s mystical thinking about marine biology eventually converged with Leopold’s ethic of wildlife biology to create the field of conservation biology and the holistic vision of today’s environmental movement.

Leopold and Ricketts, opposites types in personality and behavior, come to life like the parallel protagonists of a Steinbeck novel in Lannoo’s elegant little book. Like all prophets, both men had their problems with power. Though Leopold’s 1933 work on game management became the standard textbook of its time, Sand County Almanac was passed over by publishers who doubted the commercial value of any collection of essays about nature not named Walden. Ricketts’s Between Pacific Tides (1939) eventually become a standard text for teaching marine biology, but not before it was rejected, accepted with edits, then endlessly delayed by Stanford University, its publisher. As for Sea of Cortez, does anyone think Viking Press would have touched that book without John Steinbeck’s name on the byline over “E.F. Ricketts”? True, Steinbeck mourned Ricketts’s death, but he later agreed to republish Sea of Cortez, with an essay “About Ed Ricketts” but without Ricketts’s name as co-author.

Leopold and Ricketts, opposites types in personality and behavior, come to life like the parallel protagonists of a Steinbeck novel in Lannoo’s elegant little book.

Fortunately, Michael Lannoo—a practicing scientist and popular writer about conservation biology—ignores this shameful incident, and other fetishes of what one wag calls the modern Steinbeck-studies industrial complex. Instead, he concentrates on the lives and science of his told-in-tandem subjects without the literary baggage that weighs down books about the anxiety of influence and the pleasures of symmetry by professors of English. He wisely lets Leopold and Ricketts stand on their own, unfolding their parallel stories in alternating chapters with Steinbeckian skill. Robert DeMott, the scholar and fly-fisherman who turned me on to this little gem, accurately describes Lannoo’s book as “blessedly free of cant, jargon, or technical obfuscation.” Read it and rejoice, but hear its message. Like Ricketts (who quit college) and Leopold (who went to forestry school), you don’t need a PhD to enjoy the exciting story or get the scary point. The disappearance of frogs and other species, Lannoo’s primary interest, is our generation’s Dust Bowl—“the defining event,” as Lannoo reminds us, “that made ecology suddenly relevant.”

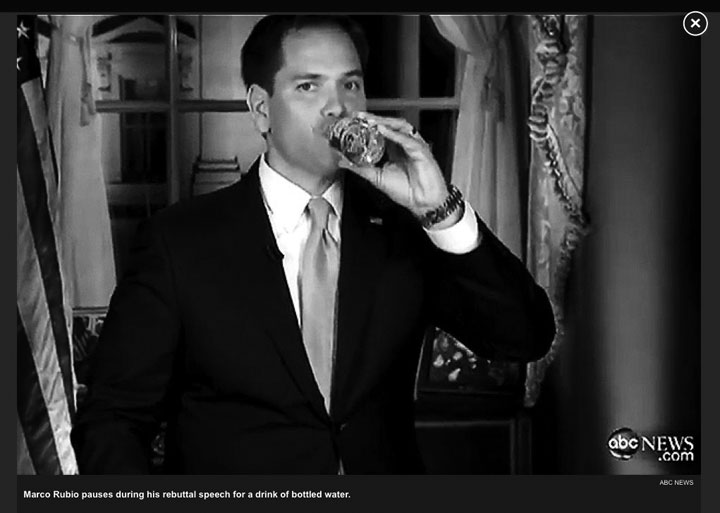

John Steinbeck Explains Marco Rubio on Global Warming in Sea of Cortez

This week the issue of global warming caused embarrassing problems for Marco Rubio as the Republican Senator from Miami rolled out his unofficial entry into the 2016 presidential race. Sorry, but I couldn’t help noticing. Although I am not a Republican and no longer live in Florida, I once owned a home on the Intracoastal Waterway near Palm Beach. During hurricanes, our little beach disappeared along with half of our yard. A two-foot sea rise will leave storm water at the new owner’s front door. Another two feet will make the house, along with thousands of other coastal homes, uninhabitable. So I’ve been scratching my head over the confused case Marco Rubio tried to articulate for doing nothing to mitigate global warming—an odd position for any elected official from South Florida to take. Oops! There goes Miami Beach!

I’ve been scratching my head over the confused case Marco Rubio tried to articulate for doing nothing to mitigate global warming. Oops! There goes Miami Beach!

As usual, John Steinbeck helped me think. Because his science book Sea of Cortez is also political and philosophical, I turned to the writer’s “Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research” in the Gulf of California to help me understand politicians like Marco Rubio who (1) deride global warming data, (2) deny that fossil-fuel use is a factor, or (3) insist that it’s too late to turn back, so what the hell! During the course of speeches and interviews in New Hampshire and elsewhere, Marco Rubio denied global warming so often and so recklessly that he became the butt of a Wednesday night Stephen Colbert Show “F*ck It!” segment. What part of Rubio’s brain shut down when he opened his campaign for president? Three observations made by John Steinbeck on the biology of belief and behavior in Chapter 14 of Sea of Cortez provided clarity, but little comfort, about Marco Rubio’s recent statements regarding global warming. Hold the applause. They are nothing to laugh about.

1. Forget simplistic causation. Find provable relationships and prepare for complexity.

Sea of Cortez starts with first principles. From microbes to mankind, variation in nature is a universal principle; causative relationships are complex and outcomes aren’t always predictable. But worldwide climate disruption is a particularly violent variation with measurable relationships and very clear consequences. Denying the significance of man-made carbon emissions in accelerating global warming by implying, as Marco Rubio and others do, that . . . well, shit happens . . . is like letting a drunk drive on the theory that other things can go wrong too, so what’s the big deal? Ignition failure, bad brakes, lousy weather, all contribute to accidents on the road. But driving while drunk, like loading the atmosphere with pollutants, foolishly increases the severity and consequences of co-contributing factors.

Driving while drunk, like loading the atmosphere with pollutants, foolishly increases the severity and consequences of co-contributing factors.

“Sometimes,” John Steinbeck would have agreed, “shit just happens.” But try taking that excuse to court and see what happens there—if you survive the wreck you caused. Steinbeck was a Darwinian who tried not to judge, but deadly driving while drunk has been described by those who are less forgiving as a form of natural self-selection for stupid individuals. Unlike solitary drinking, however, global warming denial is a social disease. Following the dimwitted herd of reality-deniers, like lemmings, over the looming climate cliff? That takes systematic self-delusion and self-styled leaders like Marco Rubio. How do they operate? John Steinbeck had a theory.

2. Reality-denial is a form of adolescent wish-fulfillment. It’s most dangerous in a mob motivated by a self-appointed leader.

Sea of Cortez—co-authored with Steinbeck’s friend and collaborator, the marine biologist Ed Ricketts—develops many of the ideas Steinbeck expressed in the fiction he wrote before 1940. His 1936 novel In Dubious Battle, for example, dramatized the murderous behavior of opposing mobs, behavior worse than anything within the capacity of their individual constituents. Steinbeck’s characterization of politically-driven leaders like Mac, the novel’s Communist labor-organizer, is particularly disturbing, even today. Sea of Cortez develops both of these core ideas—the behavior of mob members and the psychology of mob leaders—using biological terms that help explain Marco Rubio and his position on global warming.

Sea of Cortez develops both of these core ideas—the behavior of mob members and the psychology of mob leaders—using biological terms that help explain Marco Rubio and his position on global warming.

Like Steinbeck’s metaphorical ameba in Sea of Cortez, Mac the Communist and Marco Rubio the Republican are political pseudo-pods who detect a mass-wish within their followers and press toward its fulfillment: “We are directly leading this great procession, our leadership ‘causes’ all the rest of the population to move this way, the mass follows the path we blaze.” But one difference between Mac and Marco Rubio, worth noting, was apparent in this week’s events. Steinbeck’s labor agitator was a tough guy with street smarts who stayed on-message; Marco Rubio manages to look as unfixed and immature as he sounds. In right-wing global warming politics, Rick Perry—no George Bush, and take that as a compliment—seems statesmanlike by comparison. Oops! I meant Department of Education!

3. Extinction is possible. Double extinction.

John Steinbeck read encyclopedically, and in Sea of Cortez he explains what he calls “the criterion of validity in the handling of data” by citing an example from an article on ecology in the 14th edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica. It concerns the extermination of a certain species of hawk that preyed on the willow grouse, a game bird in Norway. Failing to note the presence of the parasitical disease coccidiosis in the country’s grouse population, the Norwegians systematically eradicated the predator that kept the infection under control by killing off weaker birds affected by the disease. The result was double extinction—hawk and grouse—caused by uninformed human behavior.

The Norwegians systematically eradicated the predator that kept the infection under control by killing off weaker birds affected by the disease. The result was double extinction—hawk and grouse—caused by unintelligent human behavior.

Like Steinbeck, I loved college biology, and the biology department at Wake Forest was very good. My freshman professor, a John Steinbeck-Ed Ricketts type named Ralph Amen, introduced us to an idea that makes Marco Rubio’s anti-global warming demagoguery more than a little scary 50 years later. “Imagine,” Dr. Amen suggested, “that the earth is an organism, Gaia, with a cancer—the human species, overpopulating and over-polluting its host. What is the likely outcome of this infection for Gaia and for mankind?” A question in the spirit of Sea of Cortez, which on reflection I’m certain he had read.

‘Imagine,’ Dr. Amen suggested, ‘that the earth is an organism, Gaia, with a cancer—the human species, overpopulating and over-polluting its host. What is the likely outcome of this infection for Gaia and for mankind?’

John Steinbeck, a one-world ecologist even further ahead of his time than my old teacher, would have answered, “things could go either way.” The cancer might kill the host or the host eradicate the cancer. But global warming presents a third possibility—double extinction. Now imagine that Marco Rubio is a soft, squishy symptom of global warming denial, a terminal disease. Then reread John Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez as I just did. Reality-based thinking is our first step toward a cure, although under a president like Marco Rubio it could also be our last. Oops! There we go—along with the planet! How in the world did we let that happen?

The Seeds of Death

Wherever he lived, John Steinbeck kept a garden. He believed that being close to nature and living in harmony with the earth’s ecology was an essential part of being human. What I learned about industrial agriculture on my recent trip through Steinbeck Country would make the author of The Grapes of Wrath spin in his grave.

How My Genetically Modified Food Education Began

Steinbeck—not genetically modified food—was on my mind when we set out for King City, Paso Robles, and San Luis Obispo—our ultimate destination—recently. There, on busy Monterey Street, a used bookstore beckoned with roomfuls of books on every imaginable subject. In the fiction area, high above the ‘S’ authors, hung huge photos of John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. A good sign! On the shelf below, between Gertrude Stein and Thomas Steinbeck—nothing. As the store’s manager explained, San Luis Obispo is an ecology-minded, Steinbeck-loving college town. Used copies of anything by Steinbeck are snapped up quickly. An even better sign for our Steinbeck Country weekend!

Monsanto, EPA, FDA, and Global GMO Food Disaster

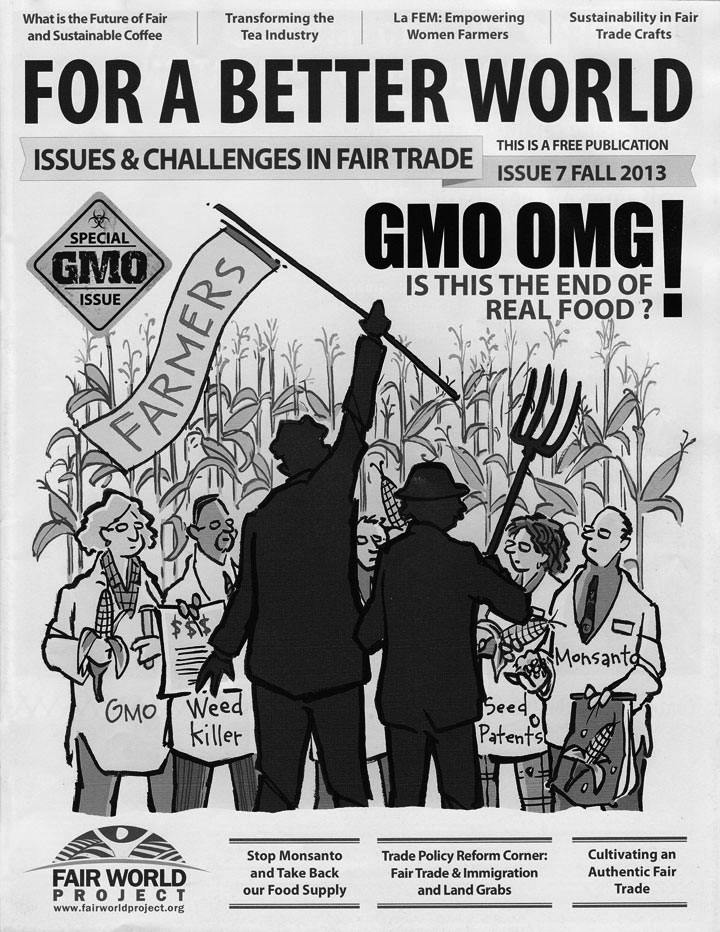

The store next door had an intriguing name: HumanKind Fair Trade. A handwritten sign by the door described the inventory and promoted the virtues of purchasing Fair Trade certified products. Inside, among colorful fabrics and hand-woven garments, a stack of For A Better World magazines caught my attention. With nothing by Steinbeck to occupy the rest of the trip, I decided to take a copy of the magazine’s special GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) issues for bedtime reading. I didn’t sleep well. I kept thinking about the helicopters overhead on Highway 101 as we made our way south through the lettuce fields surrounding Soledad, Greenfield, and King City. They were spraying pesticides.

How Monsanto, the EPA, and the FDA Collude to Control

At home I watch the news and keep up with current events. I’d heard about the controversy over genetically modified food crops and genetically modified farm animals. But until I read my copy of For A Better World that night in San Luis Obispo, I had no idea that industrial agriculture and Monsanto have colluded successfully to control the world food supply with EPA, FDA, and USDA approval. I began to wonder why the terrifying genetically modified food story isn’t on the news every night. This GMO monster is a menace to global survival, and the battle against Monsanto may be the most important call to action the world faces today. So why are so-called consumer-protection agencies like the EPA, FDA, and USDA staying on the sidelines?

EPA + FDA + USDA = Former Monsanto Executives, Monsanto Lobbyists, and Monsanto Board Members

Over the past 10 years, seven or more former Monsanto employees have held high-level positions at the FDA. Michael R. Taylor, currently the Deputy Commissioner of the FDA’s Office of Foods, was also Deputy Commissioner for Policy within the FDA in the mid 1990s. Between his last FDA job and his current one, Taylor was Monsanto’s Vice President of Public Policy. As an attorney for Monsanto, he advised the company on the legal implications of using the rBGH hormone on cattle. However, when Taylor left Monsanto for the FDA, he helped write the FDA’s rBGH labeling guidelines—guidelines which promote profits at the expense of public safety. Giant international chemical companies like Monsanto, Dupont, and Dow now effectively control the EPA, FDA, and USDA, helping push patented products—genetically modified food products, herbicides, pesticides, and hormones—past compliant legislators, regulators, and government agencies.

GMO and Roundup–Glyphosate–Are a Time Bomb

Remember Agent Orange, the Monsanto-made defoliant used in Viet Nam to kill nature and people? The company’s latest gift to ecology is glyphosate, the toxin used as a herbicide, which is now marketed worldwide under Monsanto’s friendly brand name Roundup. Here’s how Roundup works: As weeds become resistant to herbicides, genetically modified food crops require the application of more and more chemicals, including glyphosate. Glyphosate has the ability to disrupt soil ecology, effectively killing the earth where it is used. Glyphosate also binds-up soil nutrients, dramatically reducing the nutritional value of crops. Exposure to Roundup in animals has been linked to brain and immune disorders, reproductive problems, cancer, birth defects, diabetes, and more. Independent scientists warn that Roundup toxicity has been grossly underestimated by industry-friendly regulators at the EPA, FDA, and USDA. Instead of protecting the public from the threat of glyphosate toxicity, the EPA recently raised the allowable trace percentage of Roundup in farm-grown foods. You can read about it here.

GMO Food and Glyphosate: Threats to Global Health

Because the EPA, FDA, and USDA have failed to protect us, we have to do it ourselves—starting at the shelves of our local supermarket. Until the fight for mandatory GMO food labeling is finally won, anti-GMO activists advise consumers to buy only organic foods, avoid processed products, and—because you can’t tell from the label—assume that glyphosate is present unless goods are certified as organic. But glyphosate ingestion is only part of the problem with GMO foods. In independent lab tests, rats have developed horrible cancer tumors after being fed Monsanto genetically modified food products. Damage occurs at the molecular level, as the RNA from the GMO product being consumed binds with the RNA in the cells of the animal consuming the GMO. This process permanently changes the DNA of beneficial bacteria in the gut—another danger to bodily health. If you didn’t know better, you’d be right to ask why the EPA, FDA, and USDA haven’t intervened to stop this deadly cycle.

Same Old Story! Genetically Modified Food = Big Money

The United States Patent Office now allows Monsanto to patent organisms, issuing entire portfolios of patents to the company for the GMO seeds and glyphosate herbicide products Monsanto wants to see all over the world. When the company applies for a new patent, Monstanto’s attorneys claim that every GMO innovation is absolutely unique. Yet Monsanto lobbyists take the opposite position when the company petitions the FDA not to impose the GMO food labeling that is mandatory in most countries. With stunning illogic, Monstanto denies that GMO foods are any different from naturally grown products when the issue is labeling, while at the same time claiming that it has the right to patent GMO seeds as proprietary inventions.

Is Genetically Modified Food the Beginning of the End?

Once farmers convert fields to biotech crops like Monsanto’s, there is no turning back. Soil ecology is damaged by the increased application of Roundup. Genetically engineered plants are frequently sterile, so farmers must go back to the company to purchase the seeds and herbicides needed for next year’s crop. Monsanto prohibits farmers from replanting or cultivating their own seeds from patented GMO stock. Meanwhile, genetically modified pollen and seeds are spreading like a virus, carried by the wind to organically farmed fields miles away. The result? GMO pollen and seeds are now polluting organic food crops on neighboring farms, silently and without the affected farmer’s knowledge or approval. The process of contamination doesn’t end there. Glyphosate poison saturates the soil, enters streams, and may ultimately make its way into rivers and oceans. Our ecosystem is in peril today because GMO profiteers are kept in business by the compliance and collusion of EPA, FDA, and USDA officials in bed with Industrial Agriculture. It’s The Grapes of Wrath on steroids.

Act Now! Avoid GMO Foods and Glyphosate Products

Do three things today to help protect yourself from the global menace of genetically modified food and herbicide products:

- Google the words GMO, genetically modified foods, Monsanto, Roundup, glyphosate, Michael R. Taylor, EPA, FDA, and USDA.

- Pick up a copy of For a Better World and visit websites like Non GMO Project.

- Join the upcoming march against Monsanto.

To get a closer look at what ecocide by genetic modification means to you, check out this compelling video. It’s as dramatic as The Grapes of Wrath, except that its subject is the Seeds of Death being sown by Industrial Agriculture on an apocalyptic scale: