John Steinbeck’s love affairs with women, the fine arts, and the Salinas River valley come together at the 2018 Steinbeck Festival in Salinas, California when the artist and writer Janet Whitchurch talks about Underground and Running North, a new fine art book featuring her images and text. Sponsored by the National Steinbeck Center, “The Women of Steinbeck’s World” runs Friday, May 4 through Sunday, May 6 in Salinas, Monterey, and Pacific Grove and includes daytime lectures and tours, after-hour social events, and an art-feature talk by Whitchurch about the local river that inspired her book—and, like the women in his world, both inspired and frightened John Steinbeck, whose lifelong love affair with fine art and writing was fortunately less ambivalent. Don’t miss out on the variety and fun. Purchase your ticket today.

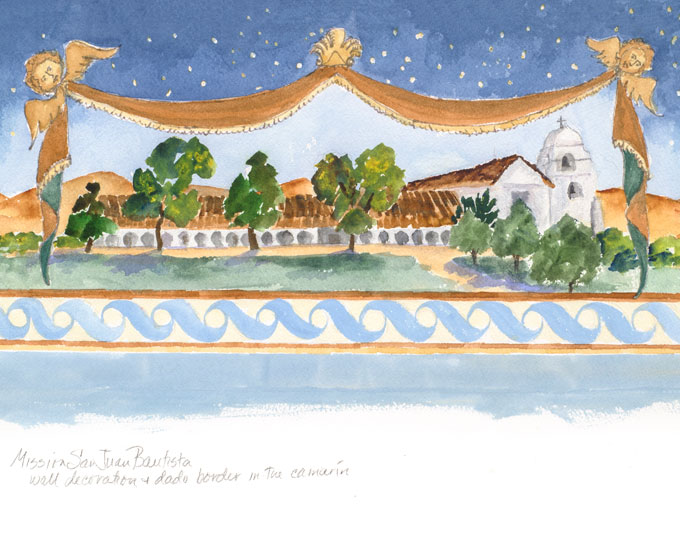

Mission Art by Nancy Hauk Mirrors Steinbeck’s History

An exhibition of art in the California mission town of San Juan Bautista by the late Nancy Hauk, whose home in Pacific Grove was once the residence of the man Steinbeck mythologized as “Doc,” will have special meaning for readers curious about the history behind Steinbeck’s California fiction. Thirty years before Steinbeck was born to the west, in Salinas, voters in eastern Monterey County, including the Mexican Californians of San Juan Bautista and Yankee settlers in Hollister, were promised their own county if Salinas became the seat of Monterey County instead of Monterey, the mission town that was California’s first capital. One outcome of this political decision was the emotional geography that came to define Steinbeck’s social sympathies and sense of place. Salinas boomed, Monterey languished, and in 1874 the County of San Benito was born, named for the river the Spanish called after St. Benedict when they built the mission they named for John the Baptist. Hollister, the nearby town where Steinbeck’s father’s family farmed and raised five sons, became San Benito’s county seat.

Steinbeck’s mother’s family lived in Salinas before the county split, and she returned to live there with her husband in 1900. He became Monterey County treasurer following a political scandal. She became the kind of local activist who took sides on civic issues like the vote of 1874. Their son’s feelings about Salinas ran in the opposite direction and eventually became material for his writing. The family’s cottage in Pacific Grove was a refuge from Salinas when Steinbeck needed one, and the Hauk house where “Doc” Ricketts once lived is nearby. So is the Monterey lab that attracted artists, misfits, and other characters celebrated by Steinbeck in his Cannery Row fiction. The conflict between Salinas and Monterey epitomized in the San Benito vote 50 years earlier was emblematic of a deeper division explored in East of Eden, the book Steinbeck wrote for his sons. Steinbeck’s art reflected his sympathies in this fight and caused controversy. Nancy Hauk’s art reminds us of the history behind the fiction.

Steinbeck’s mother’s family lived in Salinas before the county split, and she returned to live there with her husband in 1900. He became Monterey County treasurer following a political scandal. She became the kind of local activist who took sides on civic issues like the vote of 1874. Their son’s feelings about Salinas ran in the opposite direction and eventually became material for his writing. The family’s cottage in Pacific Grove was a refuge from Salinas when Steinbeck needed one, and the Hauk house where “Doc” Ricketts once lived is nearby. So is the Monterey lab that attracted artists, misfits, and other characters celebrated by Steinbeck in his Cannery Row fiction. The conflict between Salinas and Monterey epitomized in the San Benito vote 50 years earlier was emblematic of a deeper division explored in East of Eden, the book Steinbeck wrote for his sons. Steinbeck’s art reflected his sympathies in this fight and caused controversy. Nancy Hauk’s art reminds us of the history behind the fiction.

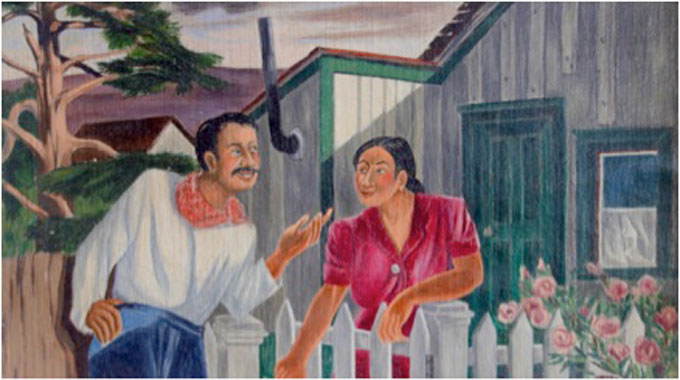

“Paintings of the California Missions,” an exhibition of work by Nancy Hauk (in photo), includes the Mission San Juan Bautista image shown here. The show has been extended and will run through May 2018.

Canadian Of Mice and Men Clowns with John Steinbeck

Of Mice and Men as feminist farce from a Canadian point of view? The November 10, 2017 Winnipeg, Canada Free Press review of Of Mice and Men and Morro and Jasp, the restaging of John Steinbeck’s novella-play by Canadian clown-duo Heather Marie Annis and Amy Lee, says the idea started in 2012, when the Canadian government reduced cultural spending and the pair got busy. In the show-within-a-show, “the clown sisters are enduring hard times due to cutbacks in arts funding” and hit on Steinbeck’s story as a vehicle for self-survival and self-expression. Morro, the Lenny sister, “hasn’t read all the way to the end and gamely proceeds without a grasp of what’s in store for her character,” and Curly’s wife is represented as a sex doll, “[layering] a feminist sensibility on the masculine-centred story.” Would John Steinbeck appreciate the purposeful appropriation? It probably helps to be Canadian, though the Winnipeg, Canada review admits the acting and humor are “a hit-and-miss proposition.”

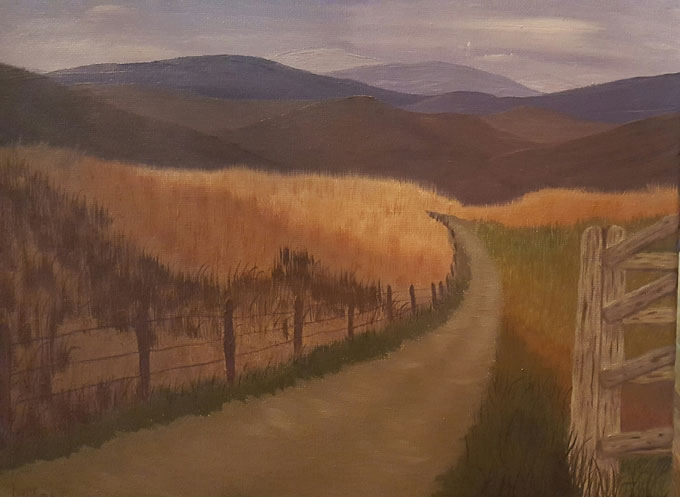

Images of the Midwest States Reflect John Steinbeck’s Affinity for the Visual Arts

This selection of paintings by Linda Holmes, a self-taught visual artist from Newark, Ohio, reflects John Steinbeck’s affinity for the visual arts—and for gifted amateurs—in life scenes from the Midwest states. Holmes, who uses oil in paintings like “Michigan Sunset” (above), also illustrates the poetry of Roy Bentley, a Midwesterner with an affinity for Steinbeck.—Ed.

Life Poem: Steinbeck’s Boat, Port Townsend, Washington

“Steinbeck’s Boat, Port Townsend, Washington”

In all the years I have been near lakes and oceans

I have never seen such blue

water

pushing gently against invisible shores,

like a lover pushes the soul to want more,

or as calm can influence a wildness

we cannot see but always are ready to feed on.

And I wonder as I look at the huge docked carcass of his boat,

if a simple remembrance

of riding a current of words that bound us together

could survive better if he had had a smaller boat, one to furl up a sail and catch

another kind of stillness.

It is then I hear a series of sighs

grey and bleak from the molded wood of this giant,

like Gregorian chants in palpable drones

emitted out loud, over and over.

They reach in unison as my organs

twist them like the Loose Strife that take over

the freshness of a Great Lake to make it treacherous,

and remind occasionally of

Ophelia.

Time may know no limit here,

this ship moored forever in ill repair,

unable to move again

in its silky sauce of decay,

and I am part of what he began in writing

and boating,

and momentary salvation is open

to the right page.

Steinbeck made sure of that

in each and every phrase,

as he is there at my shoulder

when I right the words’ direction

or float the bow into

an unsuspecting bay.

Sailboat with Furled Sail, 16″ x 20,” oil on canvas by Martha Gallagher Michael.

Sacramento, California Artist Gregory Kondos Gives “House of Steinbeck” to Pacific Grove Public Library

Gregory Kondos, a 93-year old Sacramento, California artist and immigrants’ son, recently presented “House of Steinbeck,” his painting of the legendary 11th Street Steinbeck family cottage, to the public library in Pacific Grove, the California town where John Steinbeck lived on and off in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s. The oil-on-canvas painting—based on photographs of the 11th Street cottage taken before its recent renovation—was presented to Linda Pagnella, who is retiring this week as the Pacific Grove Public Library’s director of circulation.

Kondos said that he made the gift in memory of the Pacific Grove artist Nancy Hauk (left), a close friend and former student. “I painted it in memory of Nancy,” he explained, ”as a way of honoring her.” Before Nancy’s death in July, the Pacific Grove Public Library named its newly completed art gallery in her honor. Steinbeck’s first wife, Carol Henning, may have worked at the library in the early 1930s, when the struggling newlyweds subsisted on Depression-economy jobs, help from friends, and a monthly allowance from Steinbeck’s father.

Kondos said that he made the gift in memory of the Pacific Grove artist Nancy Hauk (left), a close friend and former student. “I painted it in memory of Nancy,” he explained, ”as a way of honoring her.” Before Nancy’s death in July, the Pacific Grove Public Library named its newly completed art gallery in her honor. Steinbeck’s first wife, Carol Henning, may have worked at the library in the early 1930s, when the struggling newlyweds subsisted on Depression-economy jobs, help from friends, and a monthly allowance from Steinbeck’s father.

At Home in Pacific Grove in Steinbeck’s Time and Today

Kondos and his wife Moni have a second home in Pacific Grove, not far from the cottage where the Steinbecks lived when Steinbeck began writing Of Mice and Men. Joining the painter and his wife in presenting the painting were (from left in lead photo) son-in-law Bobby Field, associate athletic director at UCLA; daughter Valorie Kondos Field, the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame coach whose women’s gymnastics team has won six national championships; and son Steve Kondos, an Aerojet engineer who helped build the first Mars Rover. Moni Kondos made arrangements for the gift.

Location, history, and the enthusiasm of residents like Nancy Hauk, a former board member, have made the library a popular place for Steinbeck fans in Pacific Grove, a town with a long memory and a slow pace that appealed to John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. The Steinbeck cottage is located at the corner of 11th Street and Ricketts Row, the alley named by Pacific Grove for Steinbeck’s friend and collaborator.

Location, history, and the enthusiasm of residents like Nancy Hauk, a former board member, have made the library a popular place for Steinbeck fans in Pacific Grove, a town with a long memory and a slow pace that appealed to John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. The Steinbeck cottage is located at the corner of 11th Street and Ricketts Row, the alley named by Pacific Grove for Steinbeck’s friend and collaborator.

Kudos for Kondos in Sacramento, California’s Capital

Further proof that prophets, authors, and artists aren’t always without honor at home in California was provided several years ago by Sacramento, which renamed a city street Kondos Avenue. Sacramento City College, where Kondos taught until 1982, named its art gallery for him when he retired. A member of the National Academy of Design, Kondos has also exhibited in China, Europe, and Washington, D.C.

Photo of Bobby and Valorie Kondos Field with Steve and Gregory Kondos courtesy Steve Hauk.

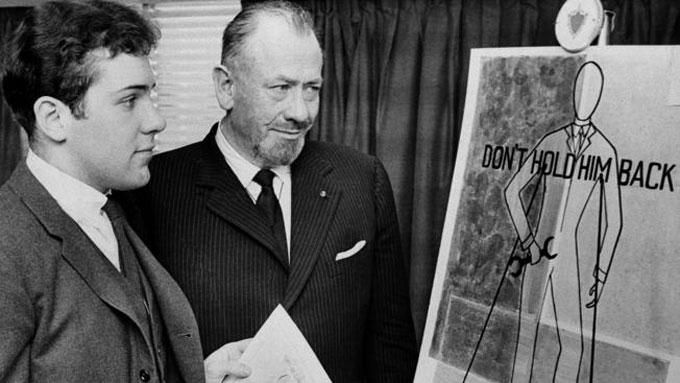

Passed On: John Steinbeck’s Affinity for the Visual Arts

John Steinbeck not only liked being painted, he liked artists and had a deep affinity for the visual arts. For much of his life he counted artists among his most trusted friends. His appreciation for the visual arts, and the needs of working artists, started on the Monterey Peninsula and continued in New York. As suggested by this undated photograph of Steinbeck with his son Thom, he passed this appreciation on to his children. As a result, of the great American writers of the 20th century perhaps none has been captured in portraits and drawings as often as John Steinbeck.

I think there are two main reasons for Steinbeck’s attraction to artists and being a subject of their work. The place where Steinbeck lived for much of his first 40 years, California’s Monterey Peninsula, was thick with gifted artists when Steinbeck was growing up and beginning his career. And because what Steinbeck was writing in the 1930s and 40s did not make him particularly popular with the local establishment, even endangering him, his circle of friends was necessarily limited, and included artists. This connection with artists carried over when Steinbeck moved to New York and eventually extended to Europe as well. I have a 2001 letter from the late Thomas Steinbeck in which he wrote, “By the time I showed up on the scene, my father had already sat for a number of notable painters.’’ Thom “showed up’’ in New York City, where he was born to John Steinbeck and Gwyndolyn Conger in 1944.

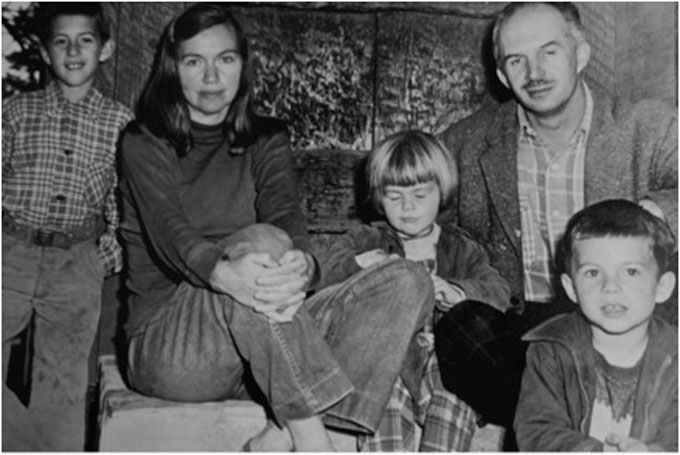

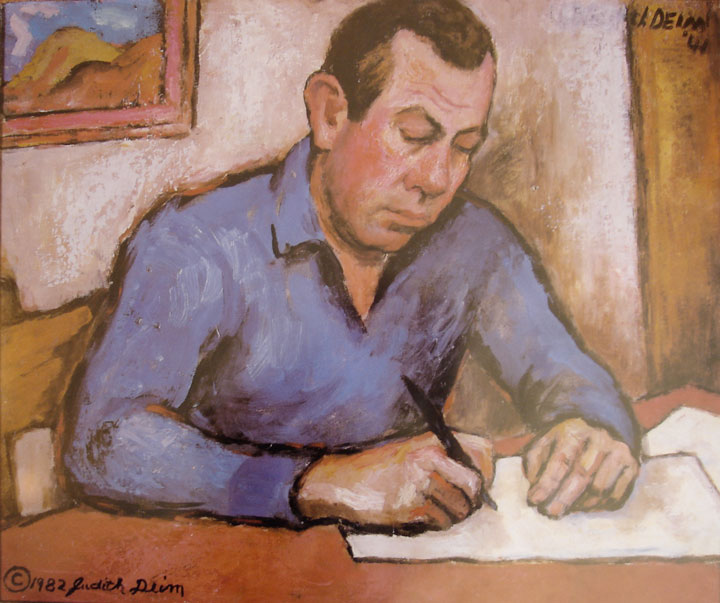

Three major portraits of Steinbeck that we know of were made before he left California for New York. One was by James Fitzgerald. The other two were by the husband-and-wife artists Ellwood Graham and Judith Deim, shown here with their children in an unattributed photograph from the late 1940s or early 1950s.

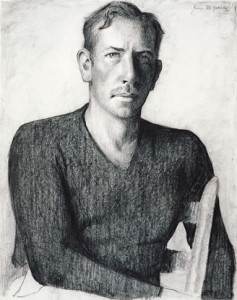

Fitzgerald was born in Milton, Massachusetts and arrived in 1928 as a seaman aboard a freighter. Once he settled in Monterey, he became a part of the group of writers and artists who gathered at Ed Ricketts’s legendary lab on Cannery Row. In 1935, the year Tortilla Flat was published, Fitzgerald did this charcoal study of a young, gaunt Steinbeck, his face half in shadow, that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Reportedly Steinbeck and Fitzgerald had their disagreements, but their friendship endured. There is a photograph of Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and Ricketts standing on Cannery Row with improvised musical instruments in their hands, including pots and pans. Fitzgerald left Monterey in 1943 for Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine; several years ago the Monhegan Museum established the James Fitzgerald Legacy in honor of his standing as one of America’s greatest watercolorists.

Fitzgerald was born in Milton, Massachusetts and arrived in 1928 as a seaman aboard a freighter. Once he settled in Monterey, he became a part of the group of writers and artists who gathered at Ed Ricketts’s legendary lab on Cannery Row. In 1935, the year Tortilla Flat was published, Fitzgerald did this charcoal study of a young, gaunt Steinbeck, his face half in shadow, that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Reportedly Steinbeck and Fitzgerald had their disagreements, but their friendship endured. There is a photograph of Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, and Ricketts standing on Cannery Row with improvised musical instruments in their hands, including pots and pans. Fitzgerald left Monterey in 1943 for Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine; several years ago the Monhegan Museum established the James Fitzgerald Legacy in honor of his standing as one of America’s greatest watercolorists.

Graham and Deim were both born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1911. Sometime in 1936 or 1937 they met Steinbeck and Ricketts–who were on their way to Mexico–while working on a WPA mural project at the Ventura Post Office in Southern California. The fiction writer and the marine biologist from Pacific Grove were impressed by the work and invited the young couple to visit the Monterey Peninsula, where Deim and Graham eventually settled. Steinbeck was generous, paying their way to Mexico to learn to “paint out loud,’’ advising them, Deim later wrote, to “go to Patzcuaro and not to Tasco where all the tourists go.’’

In 2000 Deim wrote that when Steinbeck and Ricketts returned from their expedition to the Sea of Cortez in 1940 “there was much rejoicing, partying, storytelling at the Lab. After a few days of this . . . John felt it was time to get to work. He said, ‘Why don’t you kids paint my portrait and I shall be forced to concentrate and get on with my book.’” Deim’s modern, compact portrait of Steinbeck in the act of writing, shown here, now hangs at the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies in San Jose.

Ellwood Graham’s psychological study of John Steinbeck (above) has been missing for decades. One story says that Steinbeck’s friend, the film director John Huston coveted the painting, another that it was won or lost in a poker game. Its discovery, if it still exists, would be a major find.

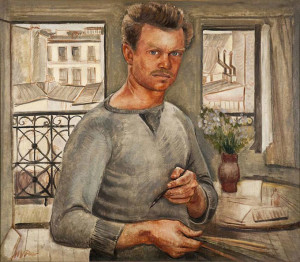

One of the first artists Steinbeck became friendly with in New York was Henry Varnum Poor, shown in this self-portrait. In the early 1940s Poor was, like Steinbeck, a resident of Rockland County, and he agreed to be a character witness for Steinbeck in 1942 when the writer applied for a New York State pistol license. This took some courage because Poor had executed a major mural in the Department of Justice building in Washington, and Steinbeck was controversial.

One of the first artists Steinbeck became friendly with in New York was Henry Varnum Poor, shown in this self-portrait. In the early 1940s Poor was, like Steinbeck, a resident of Rockland County, and he agreed to be a character witness for Steinbeck in 1942 when the writer applied for a New York State pistol license. This took some courage because Poor had executed a major mural in the Department of Justice building in Washington, and Steinbeck was controversial.

In 1944 John and Gwyn commissioned Poor to do a Steinbeck family portrait, with Gwyn holding a crying infant Thomas. It’s a stark painting. Thom, who disparaged his depiction by Poor in the 2001 letter, added that “My mother loved this painting above all others, which only lends credence to Mr. Poor’s interpretive skills.’’ Whatever he thought of Poor’s painting—which now belongs to the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas—John Steinbeck continued the family-portrait habit. Thom, again in his 2001 letter, noted that “before I could tear myself from the ancestral grasp, my portrait had been painted three times.’’

By maintaining his relationship with artists in New York, it’s possible that Steinbeck wanted to help keep them employed, as he had for Graham and Deim back on the Monterey Peninsula. Thom writes about his father’s close friendship in New York with “that singular genius William Ward Beecher.’’ Thom and his brother Johnnie were fascinated by Beecher’s work but were “pole-axed’’ when their father told them Beecher would paint their portrait, which they realized meant lengthy sittings, away from mischief-making. Thom later recalled that when he and John misbehaved their father took out his frustration by “shaking his fist’’ at his sons’ portraits rather than at them.

Another Steinbeck portraitist was the handsome Swedish artist Bo Beskow (left), who painted or drew the writer at least three times. Beskow remained a trusted confidant during a three-decade relationship in which the two friends exchanged letters, notes, and encouragement, sometimes under trying circumstances. Beskow’s informal 1946 portrait of a smiling John Steinbeck illustrates the fall 2012 issue of Steinbeck Review. A Beskow drawing of Steinbeck with the notation “Copenhagen, Dec. 8, 1962’’—two days before Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize speech—came to auction several years ago.

Another Steinbeck portraitist was the handsome Swedish artist Bo Beskow (left), who painted or drew the writer at least three times. Beskow remained a trusted confidant during a three-decade relationship in which the two friends exchanged letters, notes, and encouragement, sometimes under trying circumstances. Beskow’s informal 1946 portrait of a smiling John Steinbeck illustrates the fall 2012 issue of Steinbeck Review. A Beskow drawing of Steinbeck with the notation “Copenhagen, Dec. 8, 1962’’—two days before Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize speech—came to auction several years ago.

Of course artists didn’t depict Steinbeck only in portraiture. Judith Deim’s late-1930s painting “Beach Picnic’’ shows Steinbeck, Ricketts, and other members of the lab group gathered on an unidentified Monterey Peninsula or Big Sur beach. Deim said the painting, which has a pensive quality, was done when threats were being made against Steinbeck and his friends gathered around him protectively, as the composition suggests.

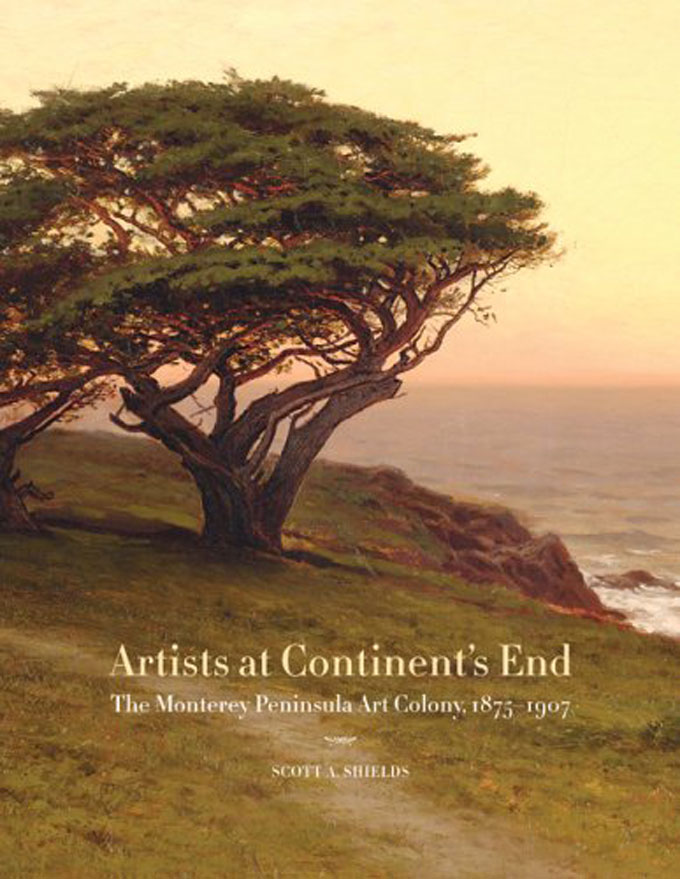

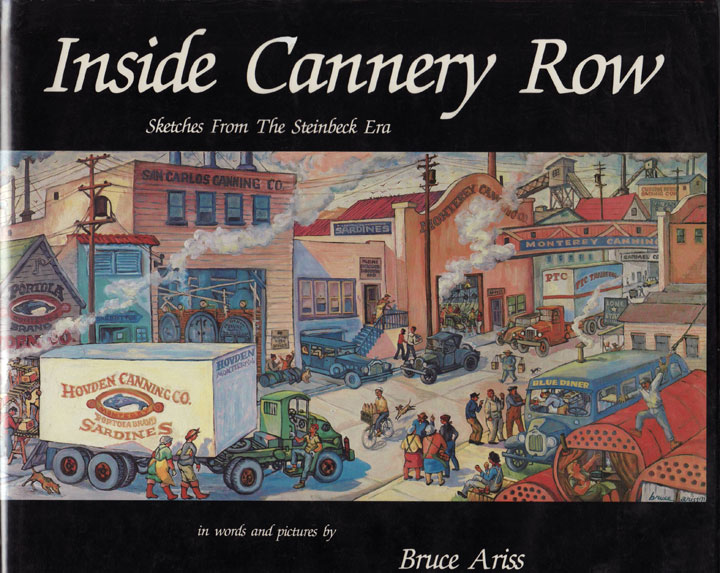

Bruce Ariss, another prominent Monterey Peninsula artist from the lab group, did an arresting drawing of Steinbeck sitting under a cypress tree watching as the characters he created parade by on a busy Cannery Row. Ariss’s spontaneous drawings of Steinbeck and Ricketts and the others populate his book Inside Cannery Row: Sketches from the Steinbeck Era. Some of Ariss’s images can be seen today on the colorful banners that dot Cannery Row.

Not all of Steinbeck’s artist friends drew or painted him. Armin Hansen and Howard Everett Smith were leading artists on the Monterey Peninsula with close relationships to Steinbeck, but I know of no portrait of the writer by either one. Hansen wasn’t really a portraitist, so it’s unlikely he painted Steinbeck. Smith did do portraits: perhaps his most famous subject was the poet Robinson Jeffers, after John Steinbeck the Monterey Peninsula’s greatest literary figure.

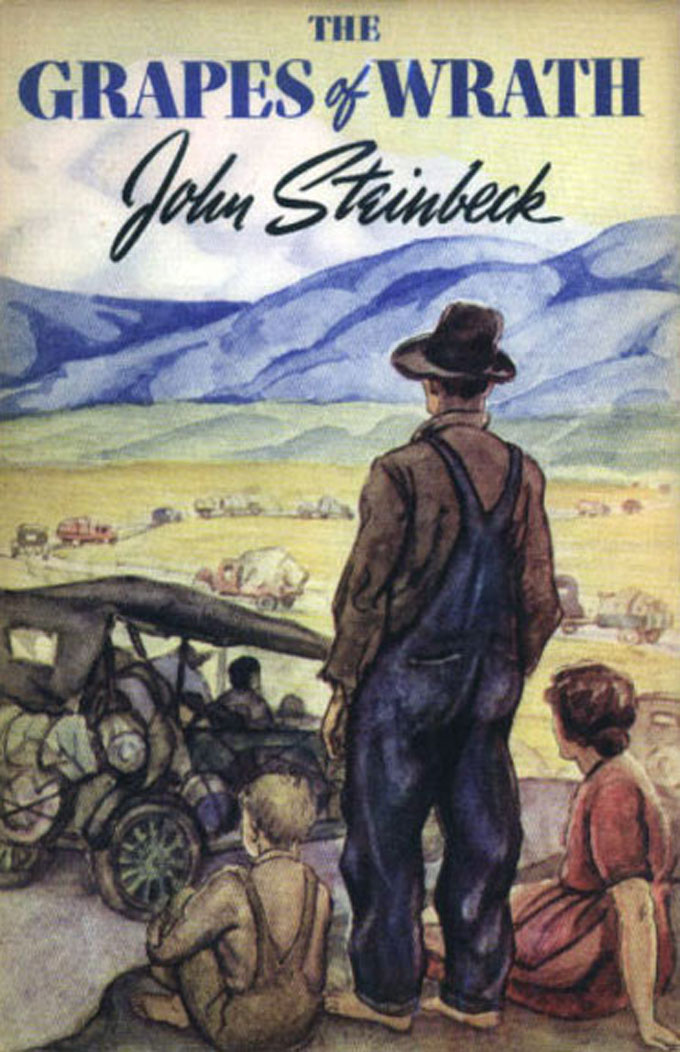

And then there were the illustrators of Steinbeck’s books. Mahlon Blaine, an artist Steinbeck met in 1925 while traveling to New York for work, created the cover art for Cup of Gold, Steinbeck’s first novel. Steinbeck was unsatisfied with the image, and he continued to be involved in selecting illustrators for many of the works that followed. To create the cover art and illustrations for the deluxe edition of Tortilla Flat like the one shown here, he helped choose Peggy Worthington (later Peggy Worthington Best), the wife of a poet and editor at Viking Press, his publisher. Thomas Hart Benton, the Missouri populist painter, was a natural choice to illustrate Viking’s deluxe edition of The Grapes of Wrath.

I’m uncertain whether Steinbeck knew Elmer Hader, the California artist who created the dust jacket for the first edition of the novel in 1939. Both Steinbeck and Hader were from Monterey County, Hader born in 1889 in the little town of Pajaro, not far from Salinas. If Hader wasn’t personally acquainted with the author, he certainly understood The Grapes of Wrath. His inspired image of the Oklahoma Joads seeing California for the first time has become almost as iconic as the characters themselves.

Some years ago I was contacted by the auction house that was putting the original watercolor for Hader’s Grapes of Wrath cover up for auction. They asked what I thought it should sell for. Guessing, I said $30,000-$35,000. That seemed high, they replied, since no Hader painting had ever sold for more than a tenth of that amount. Looking back today it’s obvious the eventual purchaser got a bargain . . . for $65,000.

I think Steinbeck would have smiled at that result. He liked artists and he wanted them to receive their due, preferably while they were alive. He passed on his affinity for the visual arts, and he did what he could to help the artists he knew.

This is the 300th post published by SteinbeckNow.com since the site launched three years ago. View the related video—Steinbeck’s Storied Artists, with commentary by Steve Hauk—from the site’s YouTube channel.—Ed.

John Steinbeck as Nude Model: Life Poem

Naked John Steinbeck

On the brocade couch, long and lean he looks beyond you

past the fact you are drawing him

and he is being drawn

past the awkwardness of his being naked

past any feelings between you two

Then he opens his mouth with a deep sigh

and a drawl only a westerner could possess

and politely, if not somewhat shyly, asks

“when will you be done?”

This impatience, like a rock thrown through an otherwise smooth clean glass

just polished with fervor,

breaks through to the flow of

in-the-moment mindfulness of seeing and transposing

the thingness of John Steinbeck naked on the couch.

As you listen to Tom Waits singing “Pony”

and the scene suddenly turns red,

then back to white on black

staying incarcerated there

in the moment

you see the dual nature of everything.

Steinbeck is grinning now, having found

his whereabouts to be comical

and your tentative nature

like another unanswered question

he forms:

“Is that what I look like without a stitch on?”

“Naked John Steinbeck,” acrylic and ink on black paper, by Martha Gallagher Michael.

Nancy Hauk, Popular Pacific Grove Visual Artist, Mourned

Nancy Hauk, the popular Pacific Grove, California visual artist for whom the Pacific Grove Library’s art gallery is named, died on July 22 after a long illness. With her husband Steve Hauk, the author of short stories based on true events from the life of John Steinbeck, she owned and operated Hauk Fine Arts, the art gallery located near Holman’s department store, a Pacific Grove landmark celebrated in John Steinbeck’s fiction. She grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and graduated with a degree in art history from Connecticut College before moving to Pacific Grove with her husband in the 1960s. Her watercolors—painted at home in California and on trips to France—were featured last year in a well-attended exhibition at the Pacific Grove Library, where John Steinbeck’s wife Carol is thought to have worked when the couple lived in Pacific Grove in the 1930s. Hauk Fine Arts specializes in the work of California artists from John Steinbeck’s era and is located near other local landmarks familiar to Steinbeck fans. These include the Steinbeck family cottage on 11th Street and the former home of Steinbeck’s friend Ed Ricketts, where the Hauks lived until Nancy moved to The Cottages, the Carmel assisted-living apartments where she died peacefully, surrounded by her husband with daughters Amy and Anne and mourned by friends and fans everywhere.

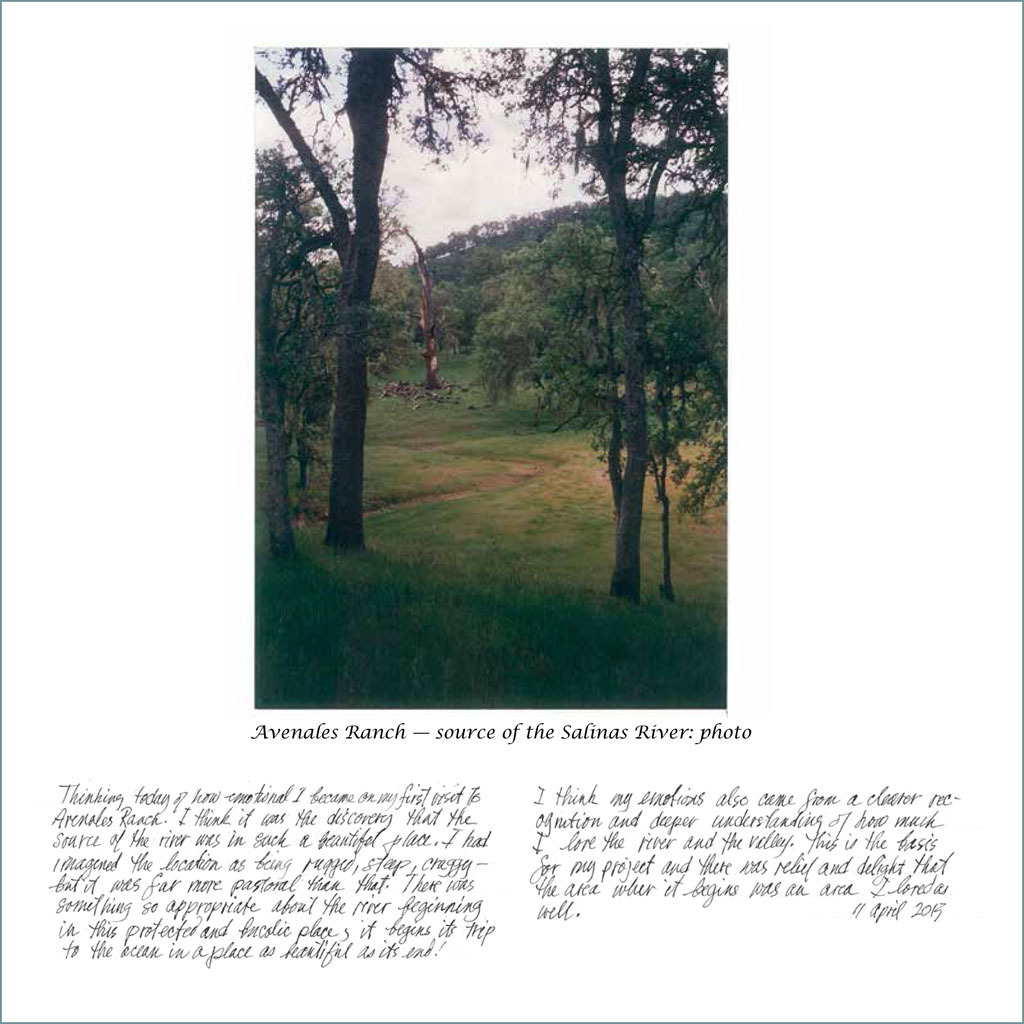

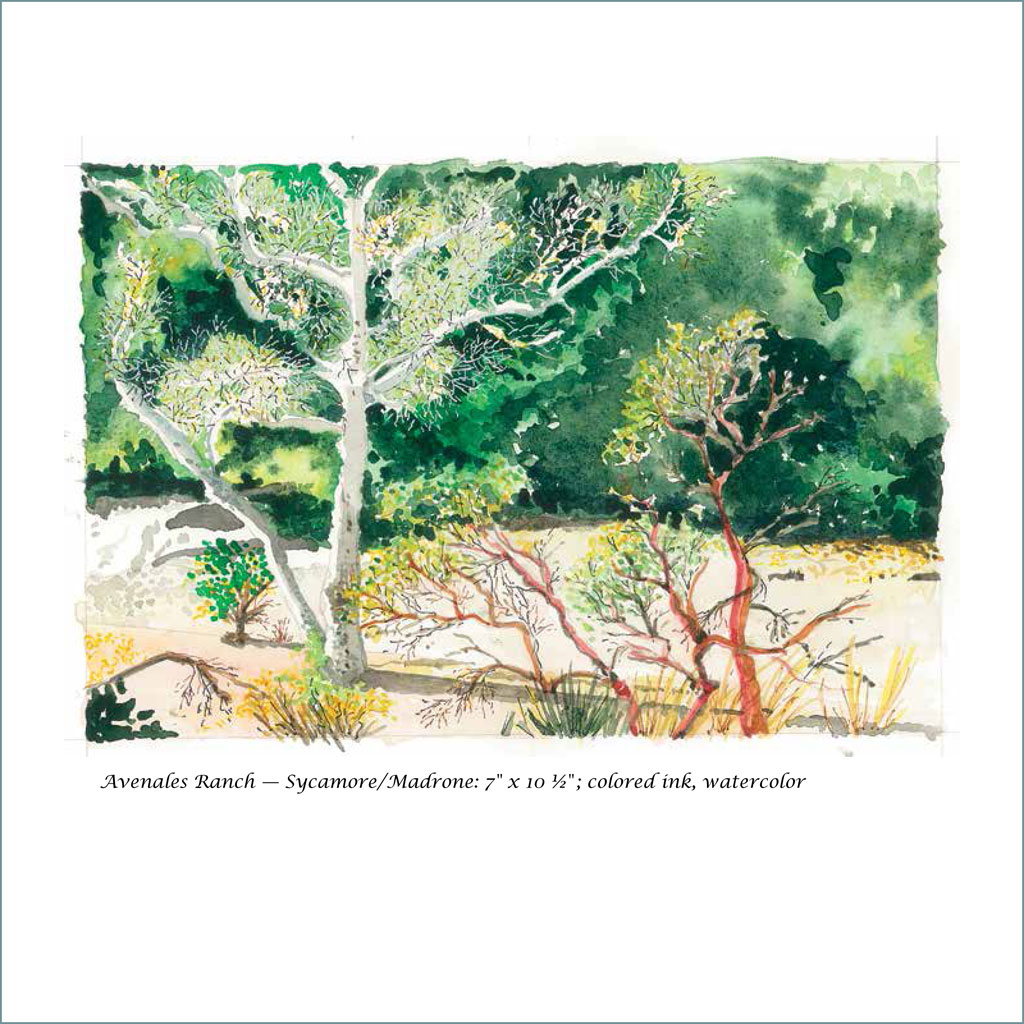

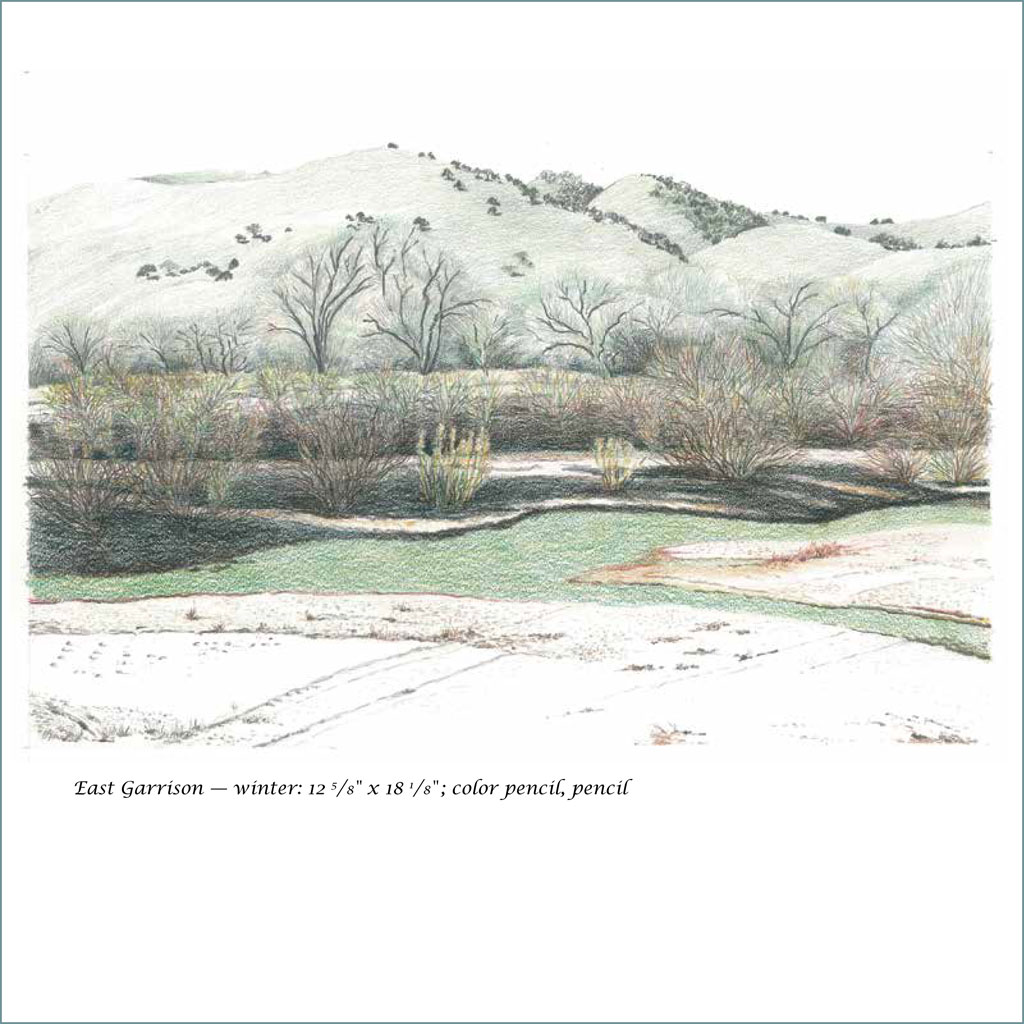

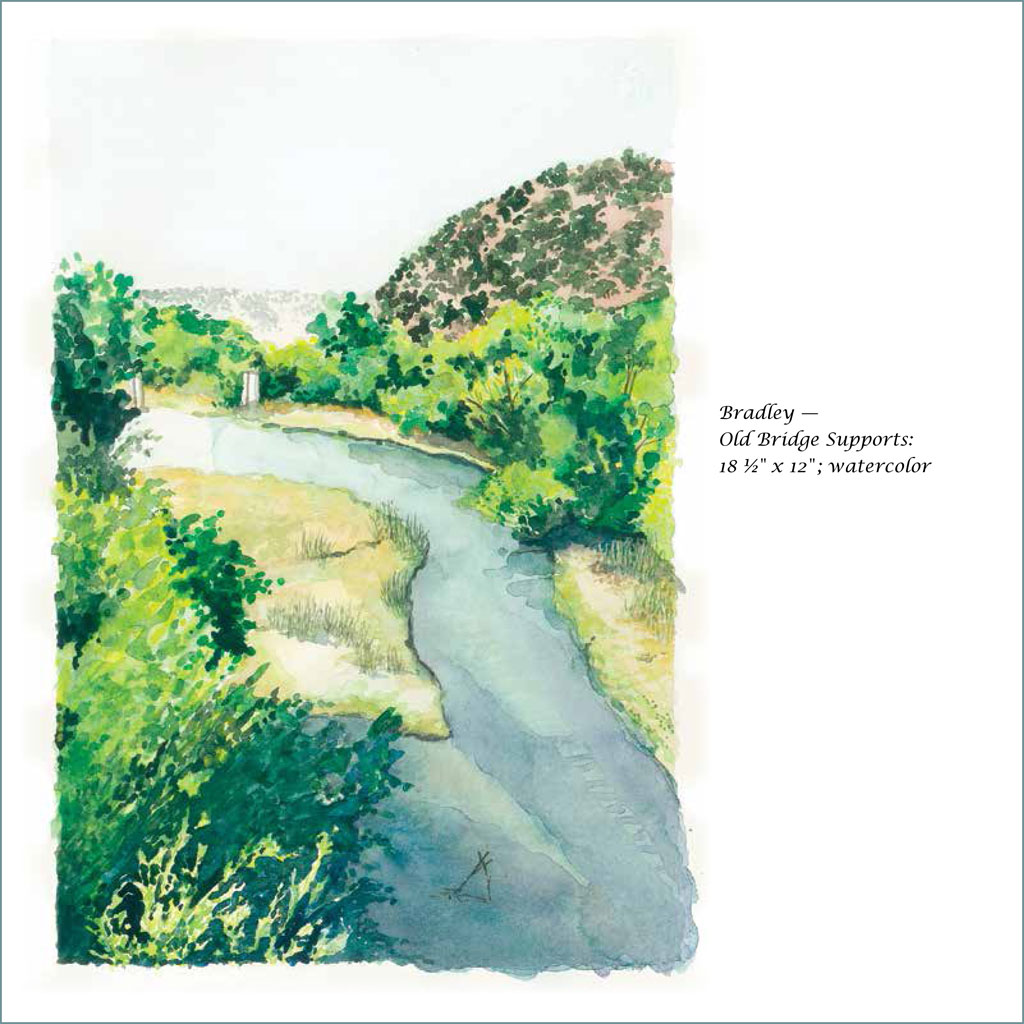

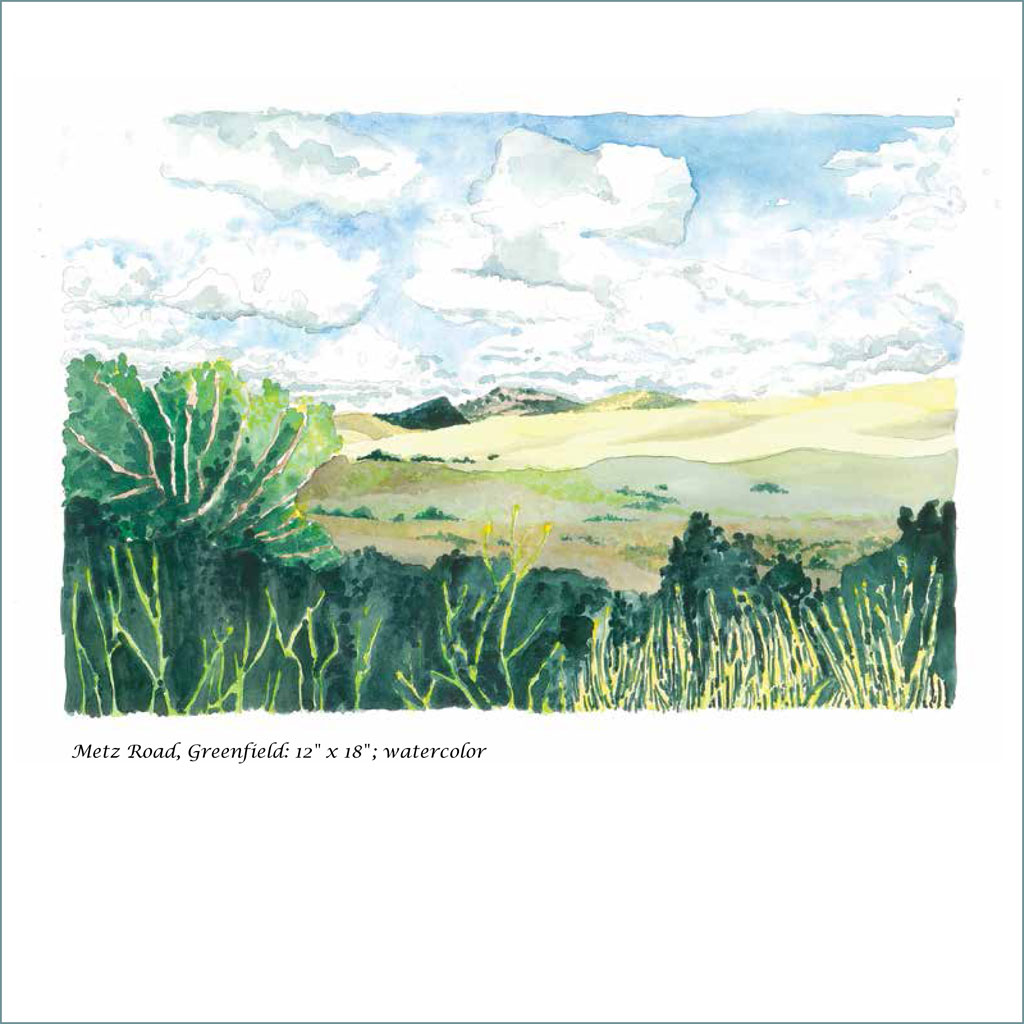

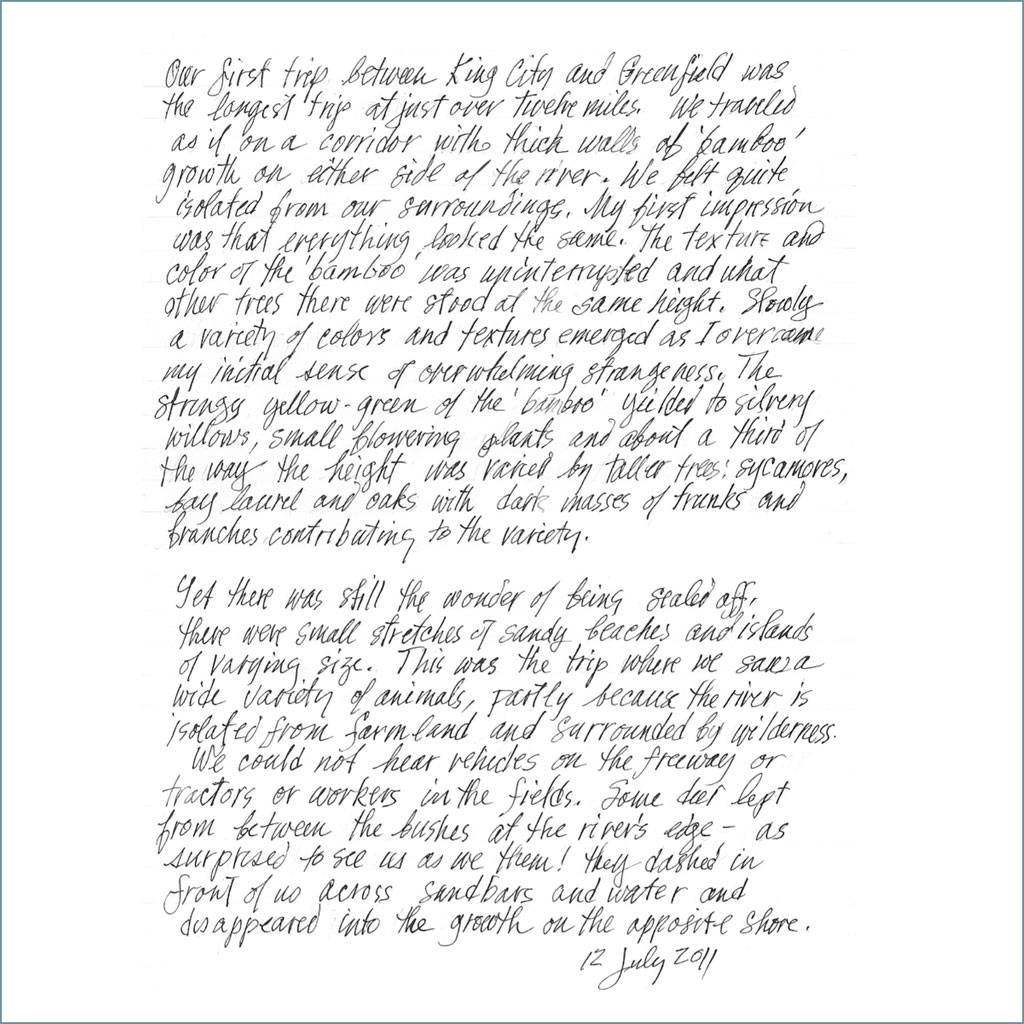

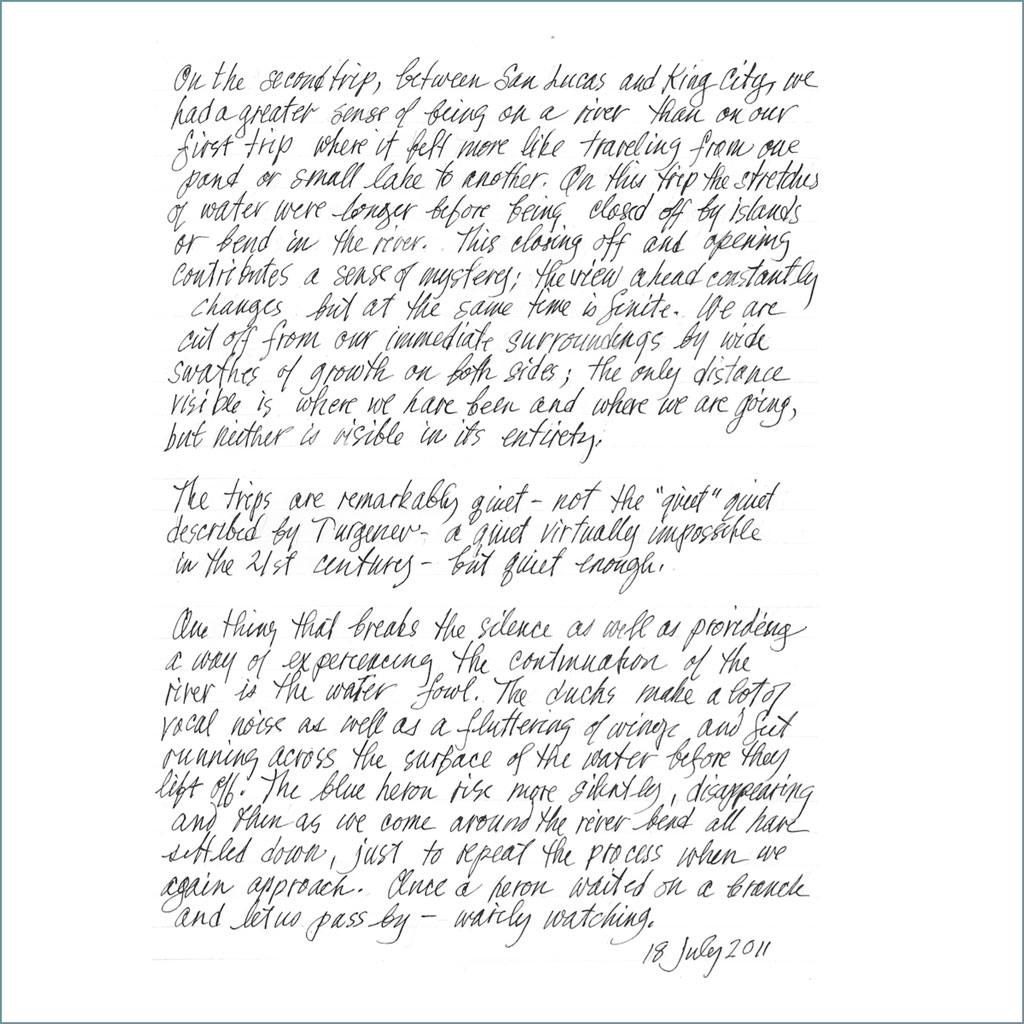

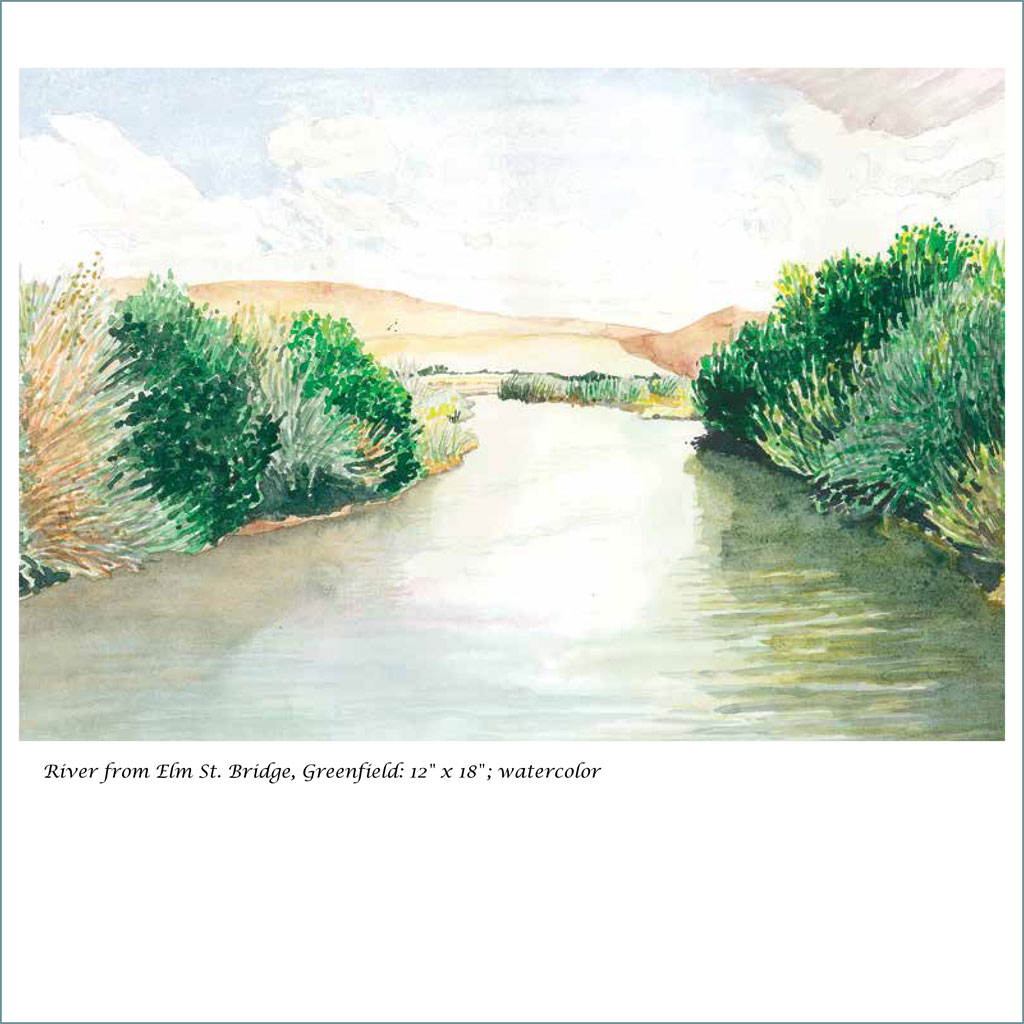

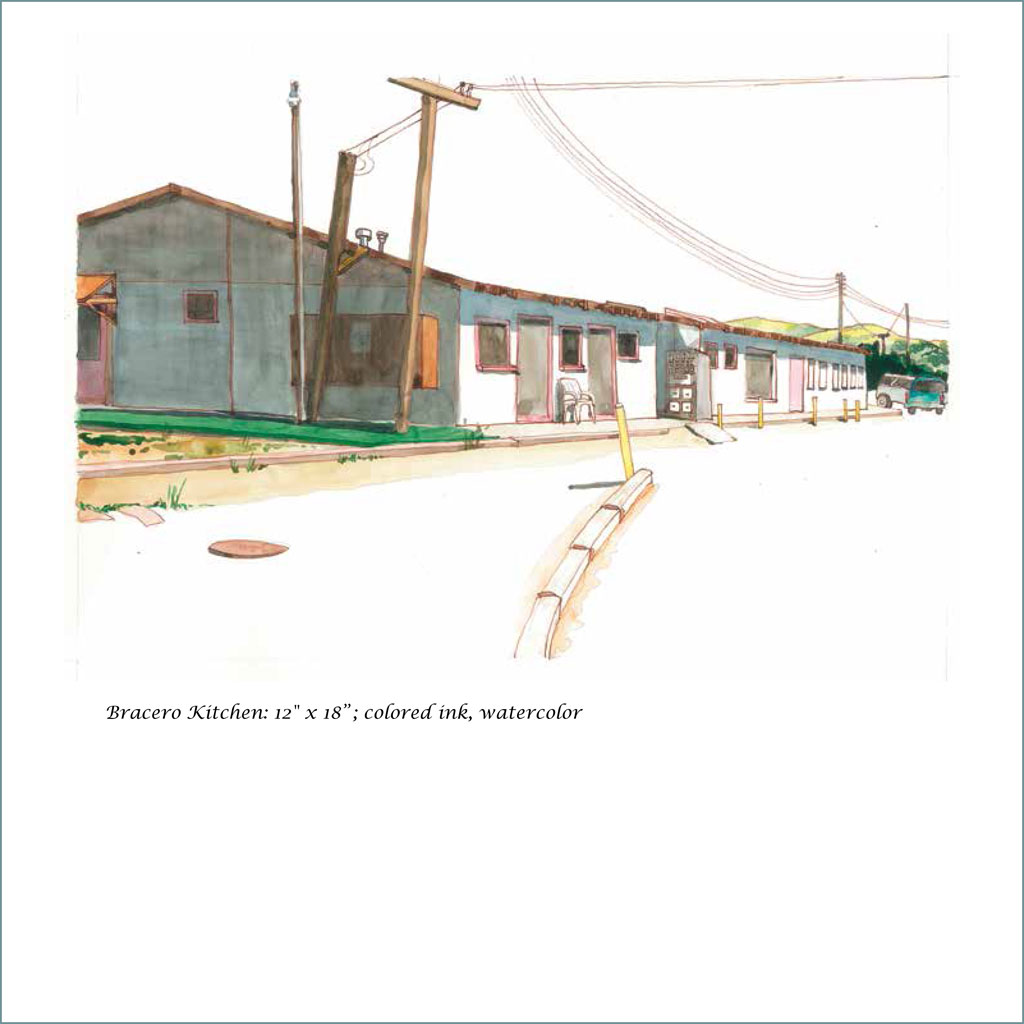

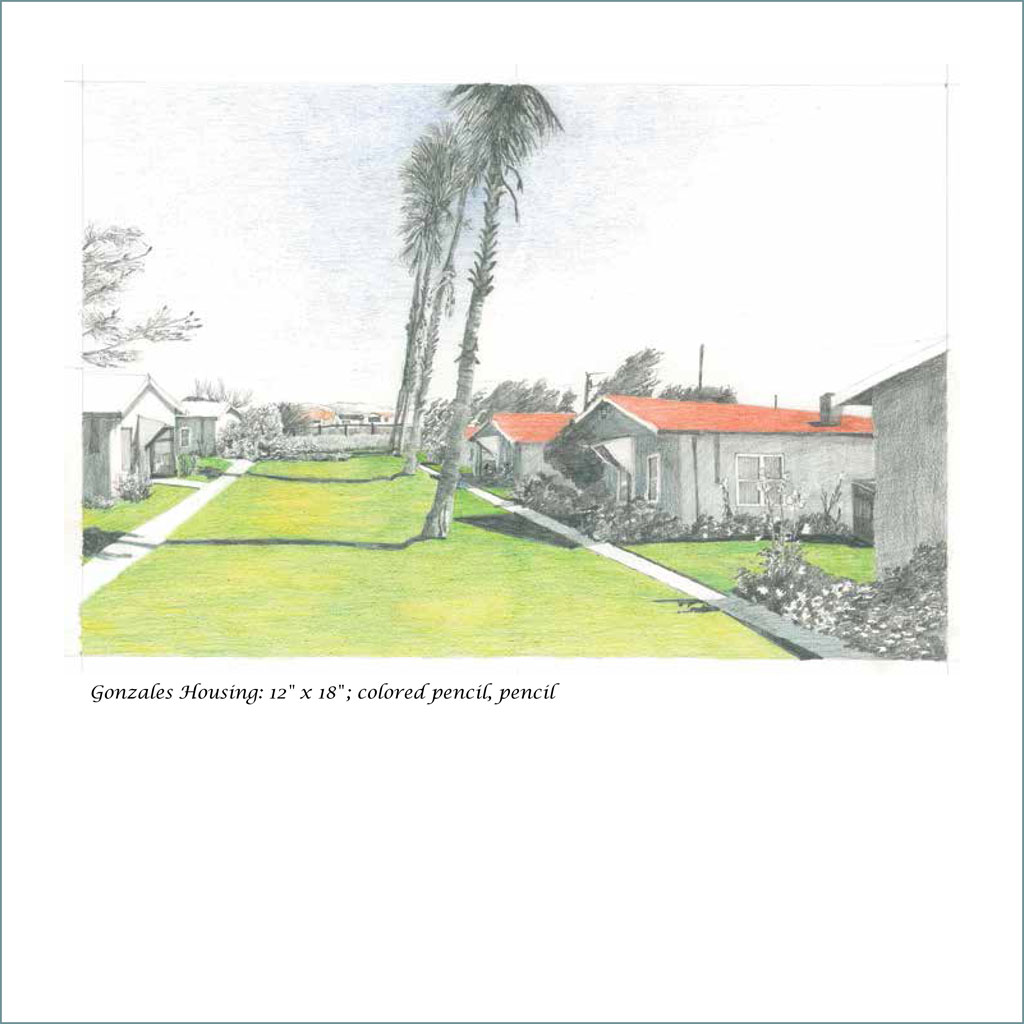

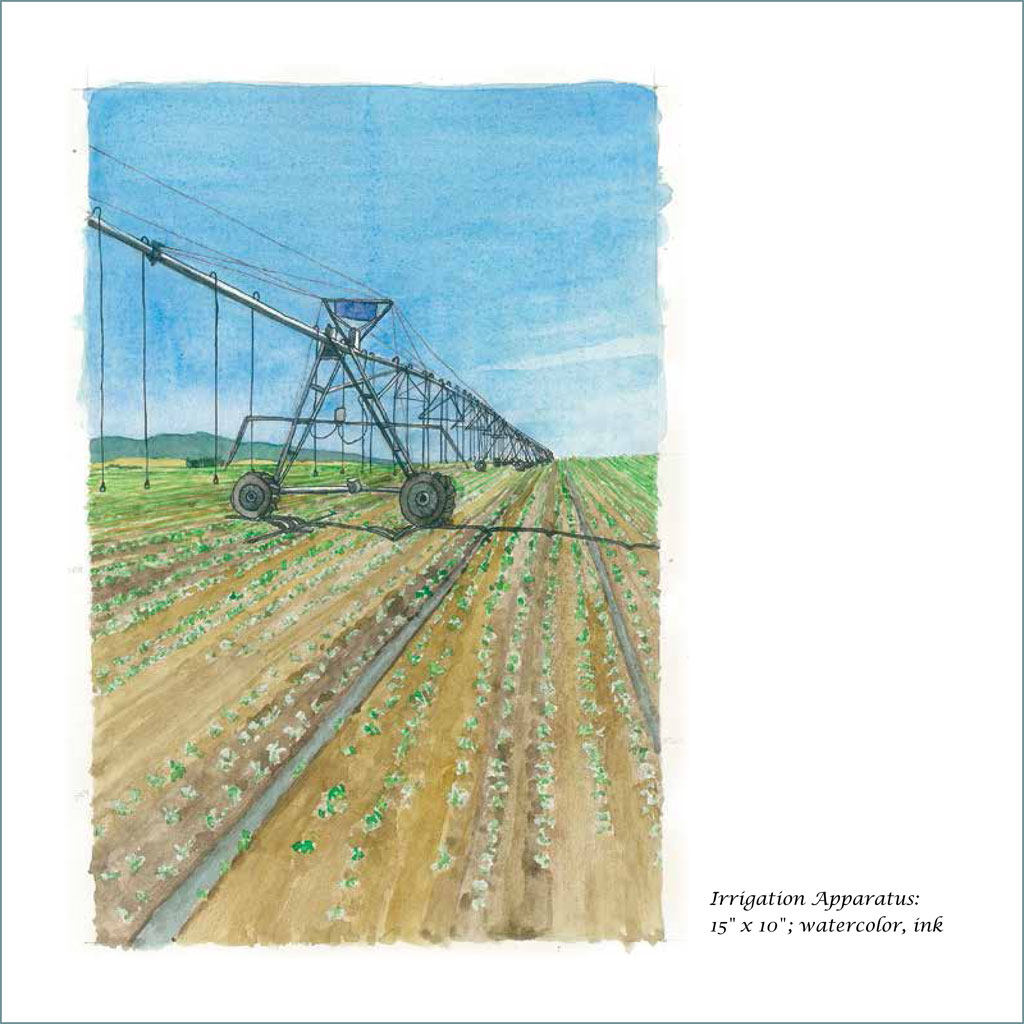

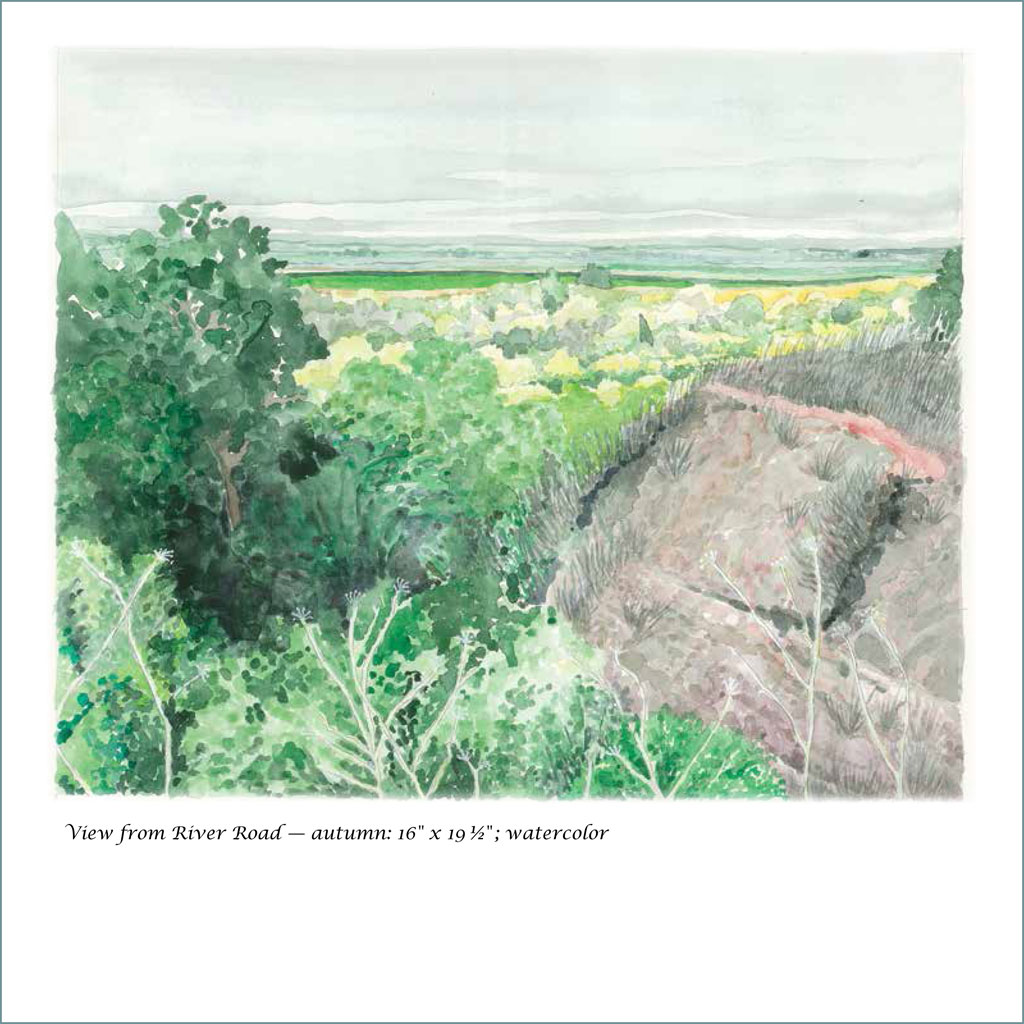

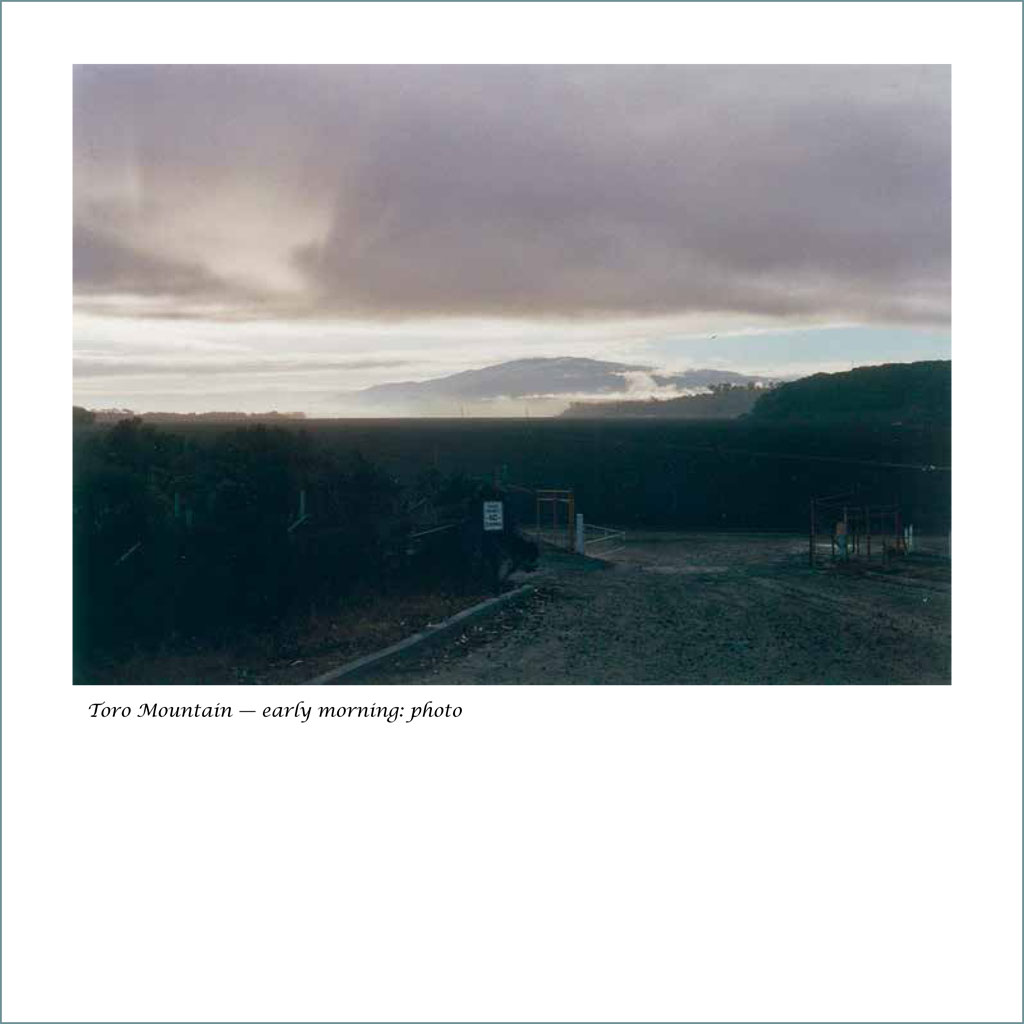

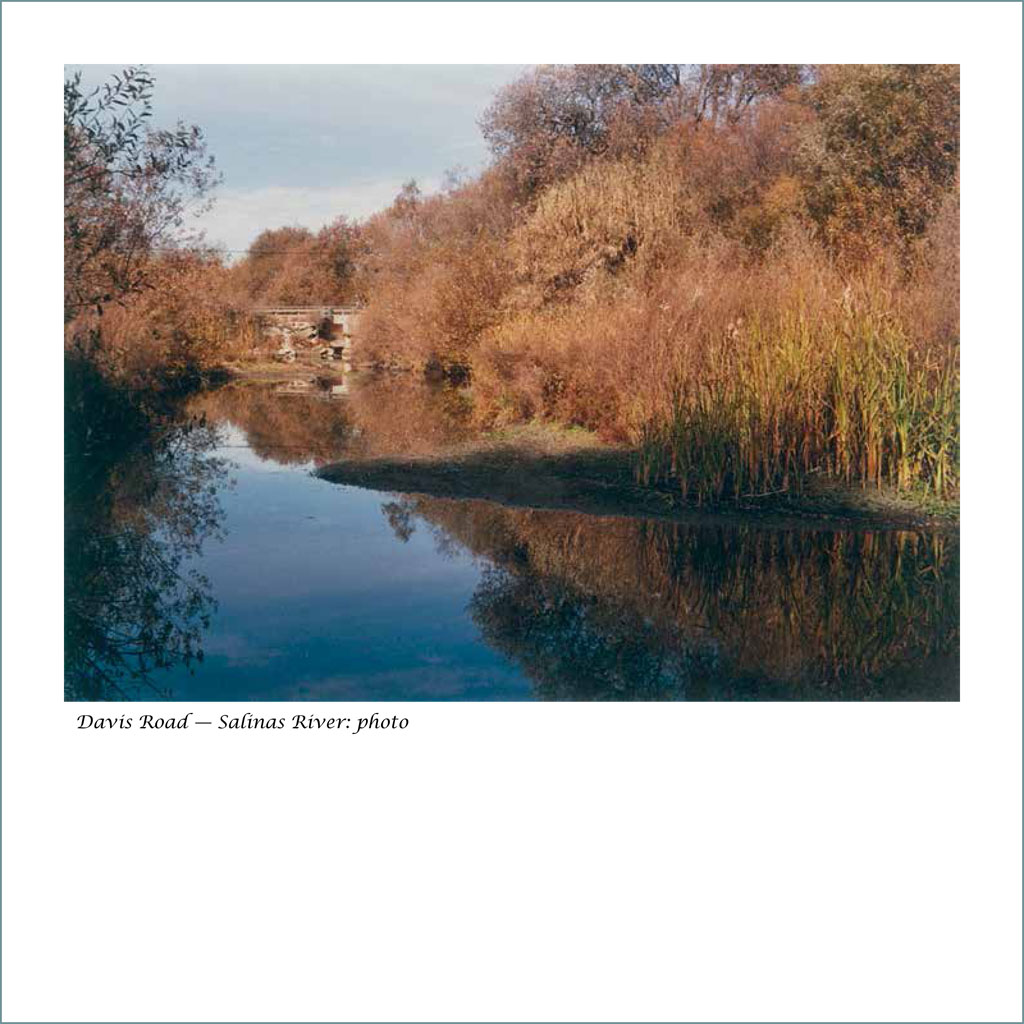

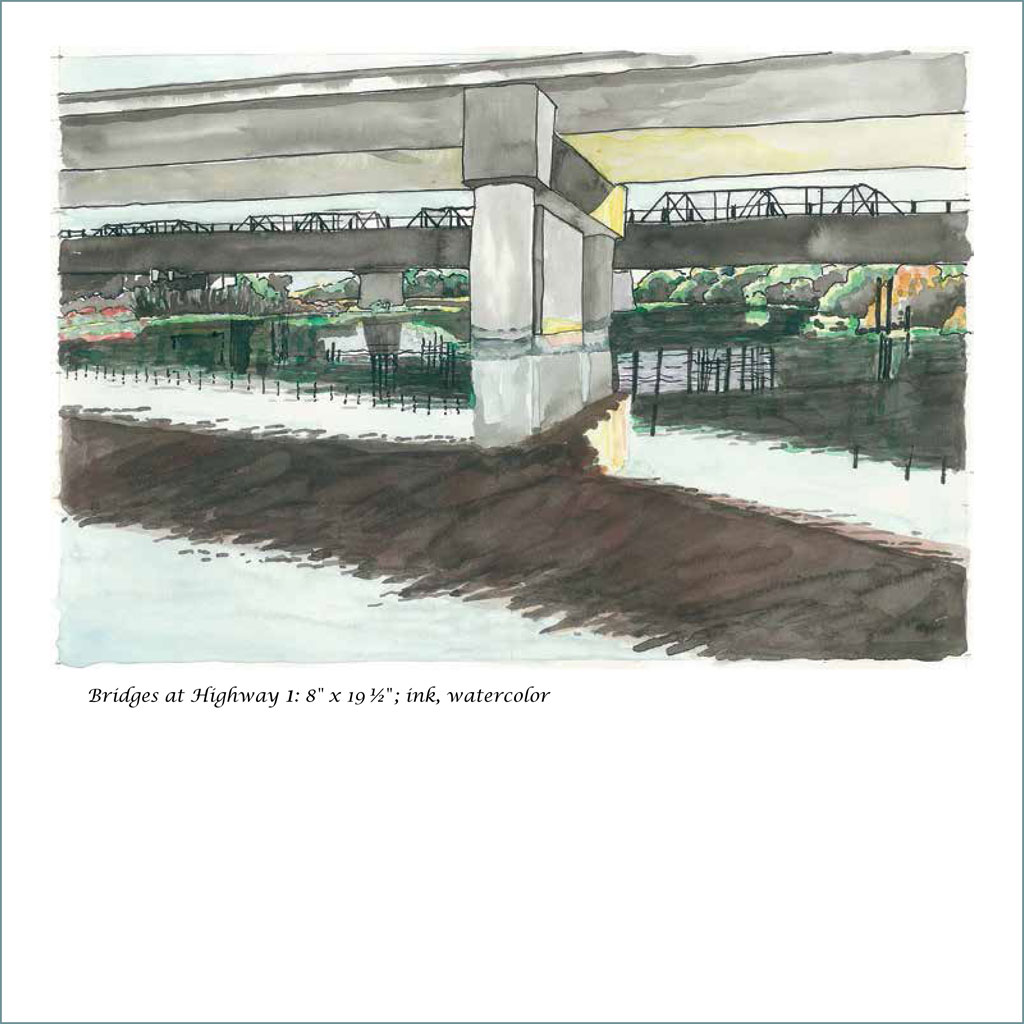

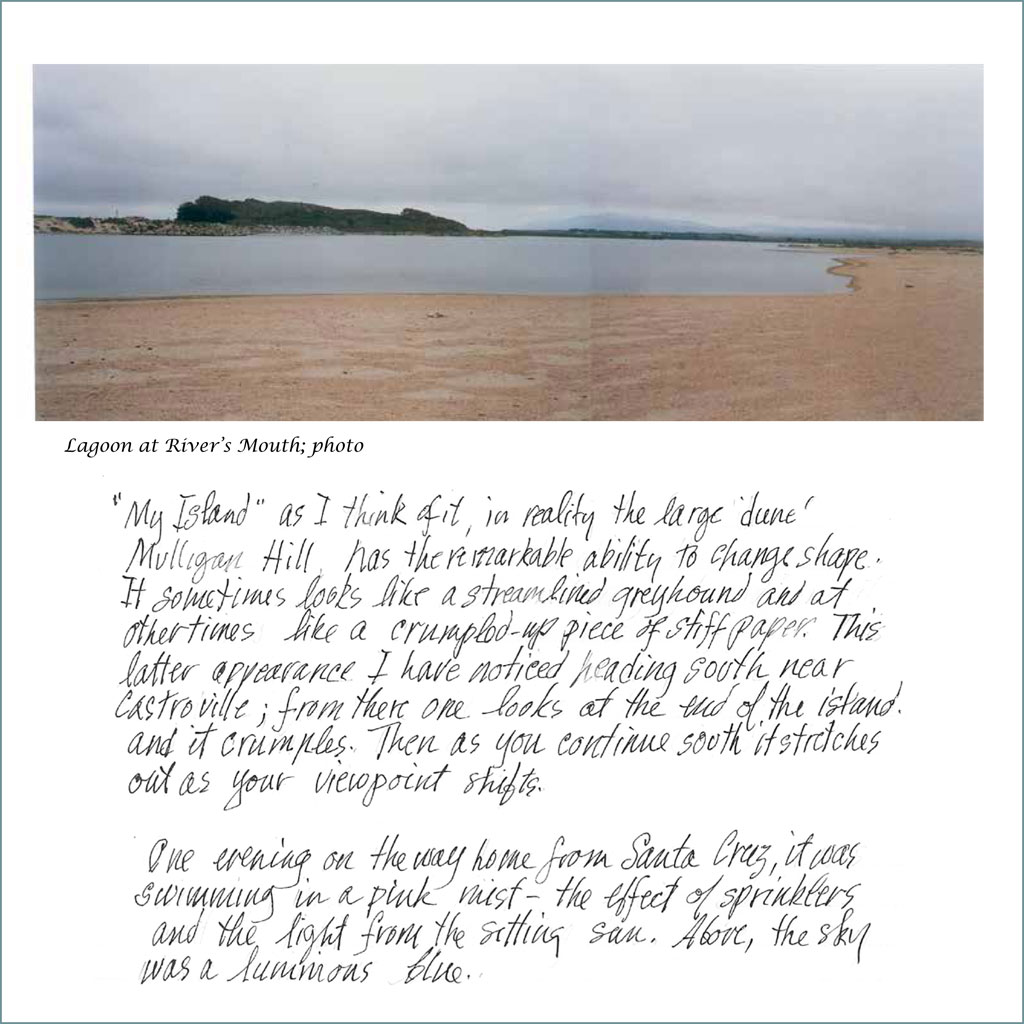

John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley and River: Image and Text in the Art of Janet Whitchurch

John Steinbeck’s imagination was occupied by the Salinas Valley and Salinas River of his California childhood. One became “the valley of the world” in East of Eden, a microcosm of nature, nurture, and culture in the turbulent unfolding of human history. The river—flowing north, like the River Nile, and underground, like the River Styx—served Steinbeck as a contrasting symbol of timelessness beyond man, like the tide pools and the stars in Sea of Cortez. Since Steinbeck wrote his books, artists in various media—watercolor painting, nature photography, narrative text—have interpreted the Salinas valley and river with a similar sense of adventure and appreciation. Janet Whitchurch combines all three—original text, nature photography, and watercolor painting—in her exploration of John Steinbeck’s valley and river, published here for the first time.—Ed.