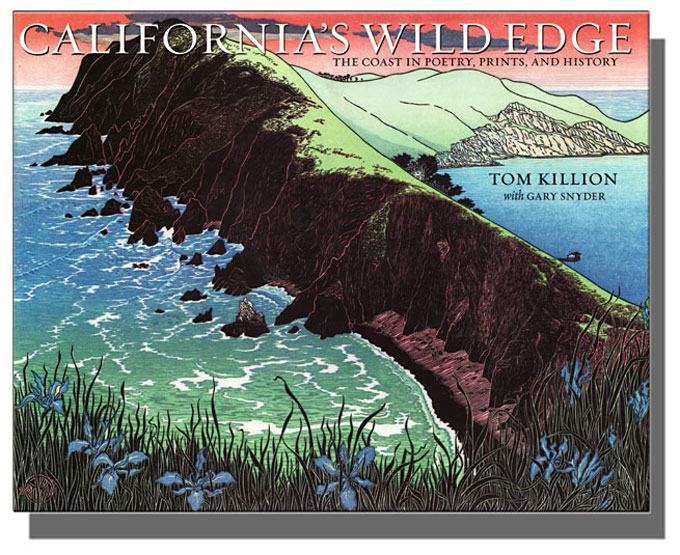

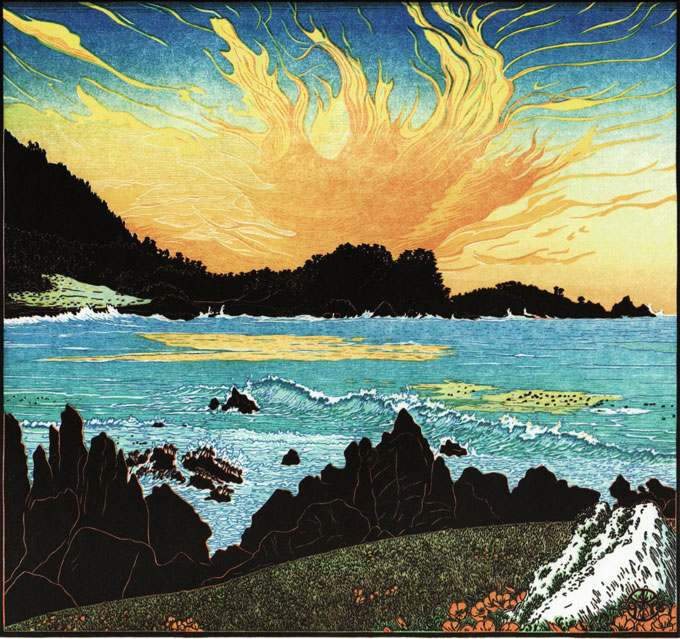

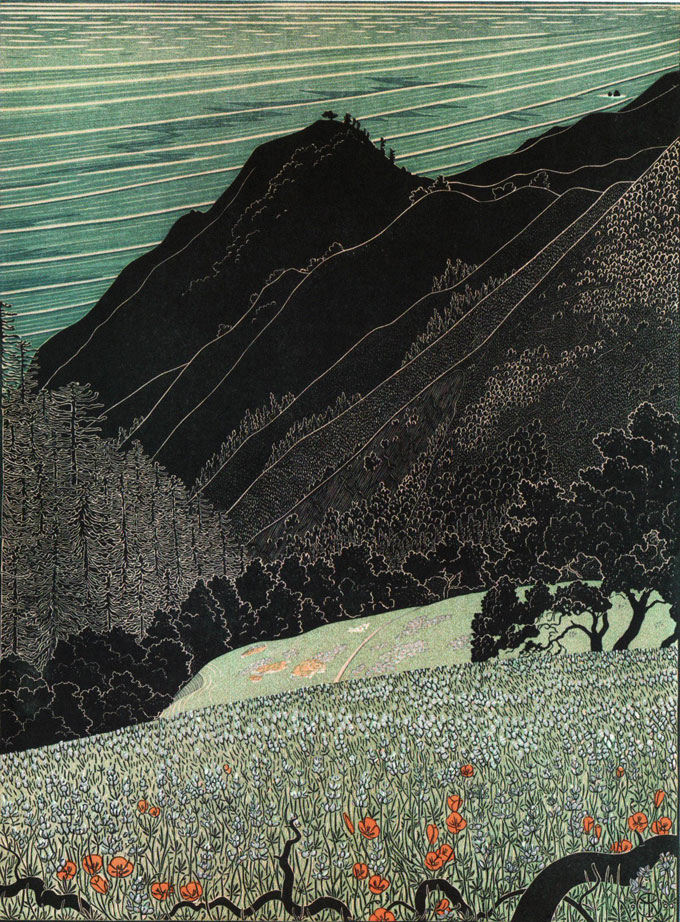

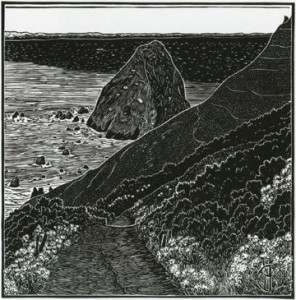

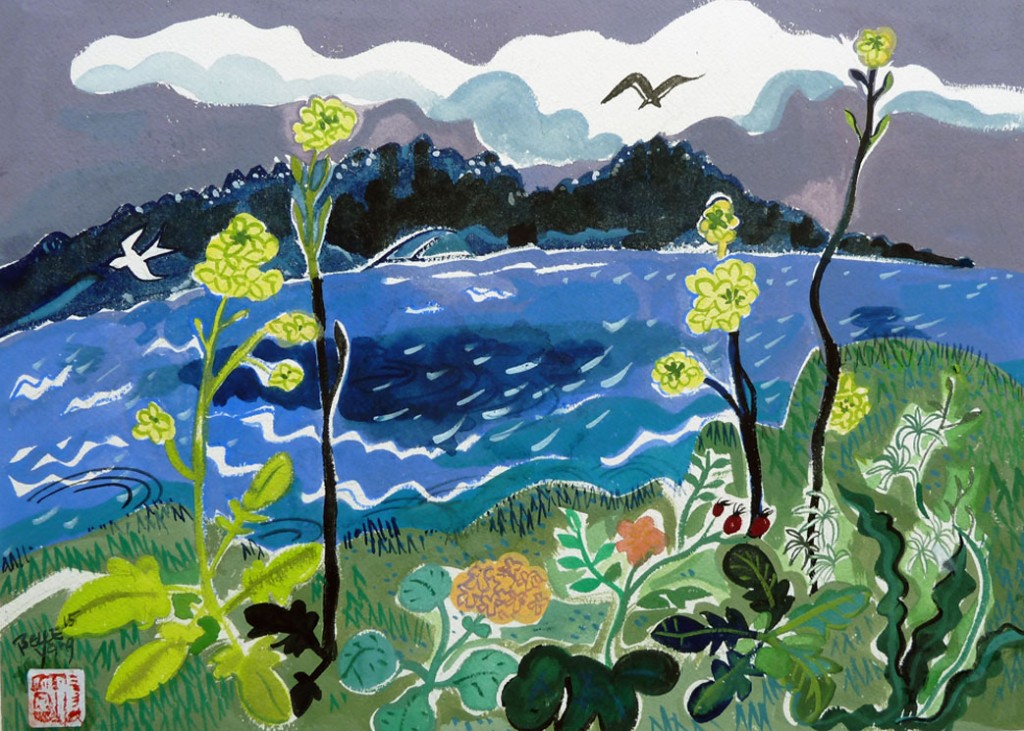

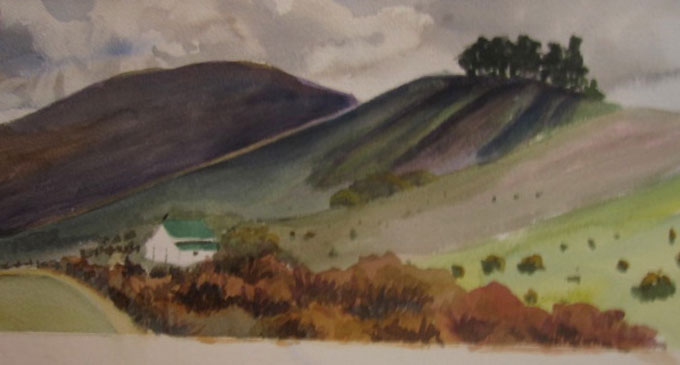

In the days before paved roads or drains or electric power lines, the hill overlooking Monterey, California was home to little more than the roaming deer and several million migrating butterflies, the latter returning each autumn to cluster on the needles of the towering pines. At the base of the trees, wild huckleberry bushes flourished. Robert Louis Stevenson knew the hill from his time when, as an impoverished Scots emigrant, he began writing Treasure Island. In his essay “The Old Capitol,” Stevenson described the 1879 Monterey, California landscape like this:

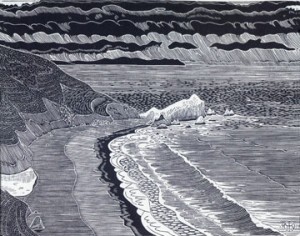

You follow winding tracks that lead nowhither. You see a deer, a multitude of quail arises. But the sound of the sea still follows you as you advance, like that of wind among the trees, only harsher and stranger to the ear; and when at length you gain the summit, outbreaks on every hand and with freshened vigour that same unending, distant, whispering rumble of the ocean; for now you are on top of Monterey Peninsula, and the noise no longer only mounts to you from behind along the beach towards Santa Cruz, but from your right also, round by Chinatown and Pinos lighthouse, and from down before you to the mouth of the Carmello river. The whole woodland is begirt with thundering surges . . . [and] a great faint sound of breakers follows you high up into the inland canyons . . . go where you will, you have but to pause and listen to hear the voice of the Pacific.

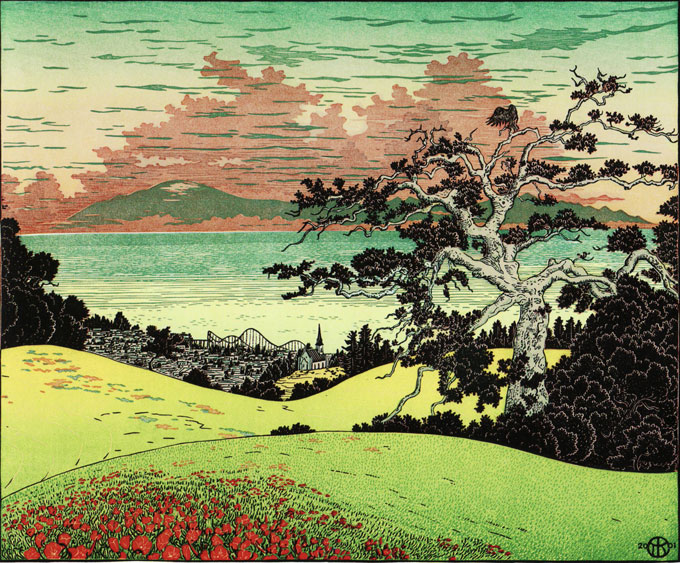

Only 30 years before Stevenson arrived, the Spanish conquistadores had abandoned their fort, the presidio built in the previous century on the hill overlooking the town that served as the center of Spanish and Mexican provincial government in California, until statehood in 1850. Even before California joined the Union, non-Spanish settlers were flocking to the Monterey Peninsula, a place of limitless beauty, abundance, and opportunity. Chinese immigrants who laid America’s railroads came and stayed to fish and raise families. Greek, Portuguese, and Italian fishermen arrived during the Gold Rush, discovering a different gold in the rich shoals of sardines that swarmed in the waters of Monterey Bay. Soon, factories that specialized in packing the fishermen’s catch into tin cans sprang up along the shore, and ever so gradually the quiet Spanish settlement of Monterey, California became an active American community. Like Robert Louis Stevenson, writers and painters were increasingly attracted to its charms, and it became a center of artistic as well as economic activity.

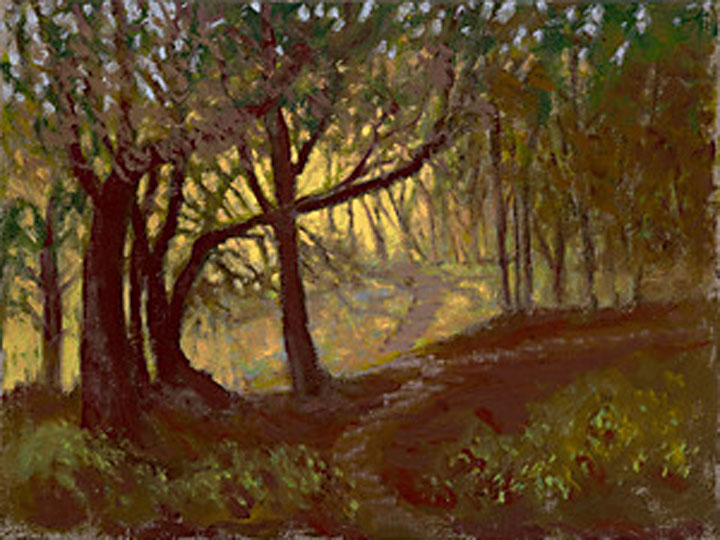

Adventurous souls who worked with charcoal and paint, those who worked with slippery hands shaping clay, others who chiseled marble and wood to make sculptures, they came together on the Peninsula seeking artistic camaraderie. There were writers and poets too, and though young John Steinbeck was not a stranger in the area—having been born in nearby Salinas—he was readily attracted to the bohemian enclave that was forming on the hill above the town. To them, the huckleberries growing beneath the pines made naming it Huckleberry Hill seem natural. Nearby, the side of the hill that looked down on Pacific Grove was, for obvious reasons, called Strawberry Flats, and the overflow of bohemian newcomers began to settle there.

Whether on the Hill or in the Flats, it was everything that Stevenson said it was, and day or night the air was clear and still: it smelled of pine and eucalyptus, and when the wind changed and came off Monterey Bay, the air would become rich with the scent of seaweed and salt. It was from there that the putt-putting sounds of the fishermen’s boats came, the cries of the gulls and the barking of the seal lions that mingled in turn with the whistles and shouts from the row of canneries now standing at the base of the Hill.

After the artists arrived, word spread that parcels of land on either side of the Hill were for sale. And they were cheap. Soon adventurous souls who were finishing their studies at Stanford or Berkeley headed south and bought 25’x60′ building lots for $25 each—though I could be wrong: they may have been 25’x100′, and the price might have been $50. The creative ones came, alone and in pairs, and houses were hastily constructed, many of them from the rough redwood boards that were harvested from the sea after barges full of redwood bound for sawmills in the south floundered in high waves, dumping their loads into the bay, where the lumber became rich pickings for those on shore.

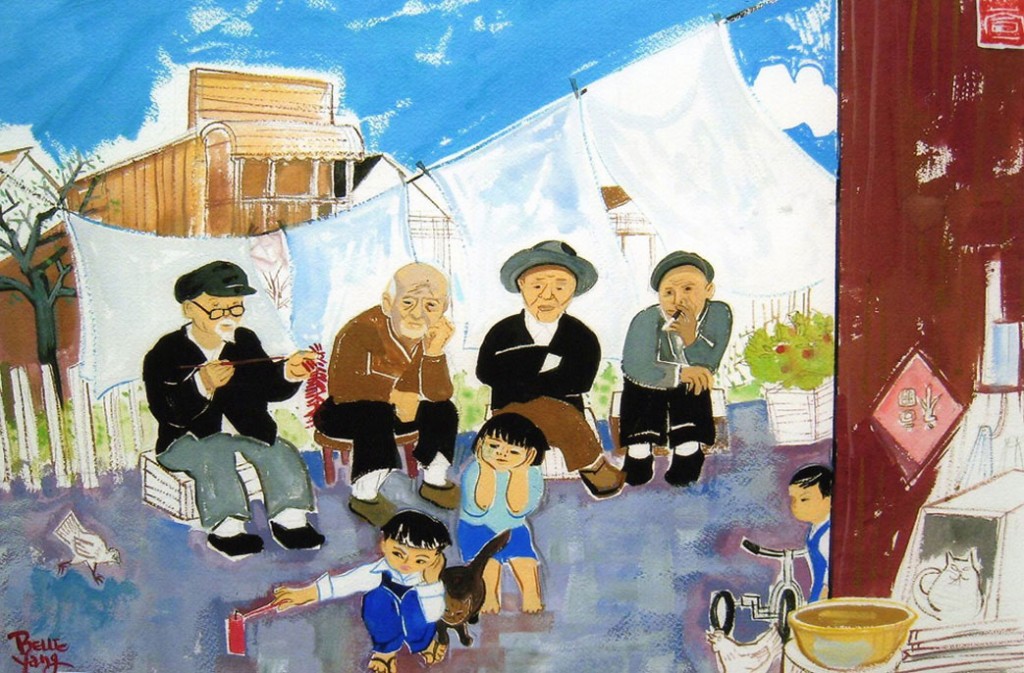

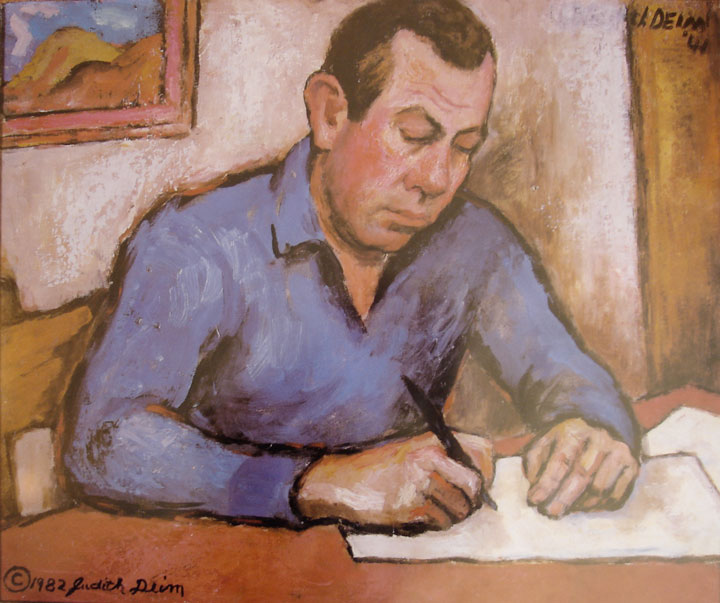

A dozen years later, the roads were covered with asphalt, drains were laid underground, and electricity poles became evident. With natural beauty at every turn, and with near-perfect weather and excellent companionship, all seemed to be going well in that best-of-all-possible-worlds, until the economic situation beyond those pine and eucalyptus groves turned bad in the 1930s and the entire country went into a long depression. The odd jobs and cannery work that helped keep the artists and artisans in bread and wine quickly vanished. However, thanks to progressive measures like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), government-funded employment eventually became available. Artists were hired to paint murals on buildings and inside the post office in Salinas, and writers were given jobs writing recipe books, travel guides, and pamphlets explaining how to can and preserve fruits and vegetables. John Steinbeck did that kind of writing, and his friend Bruce Ariss painted murals.

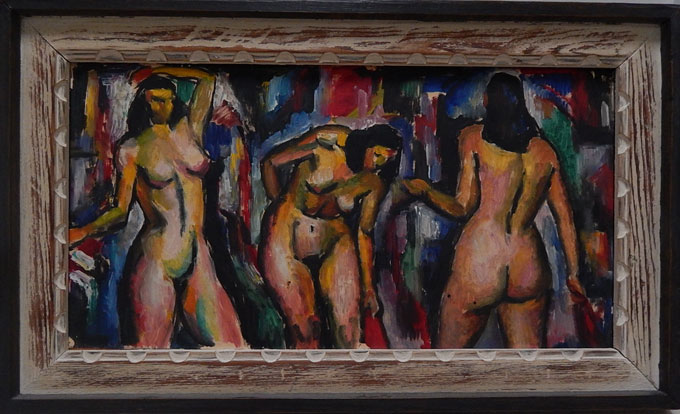

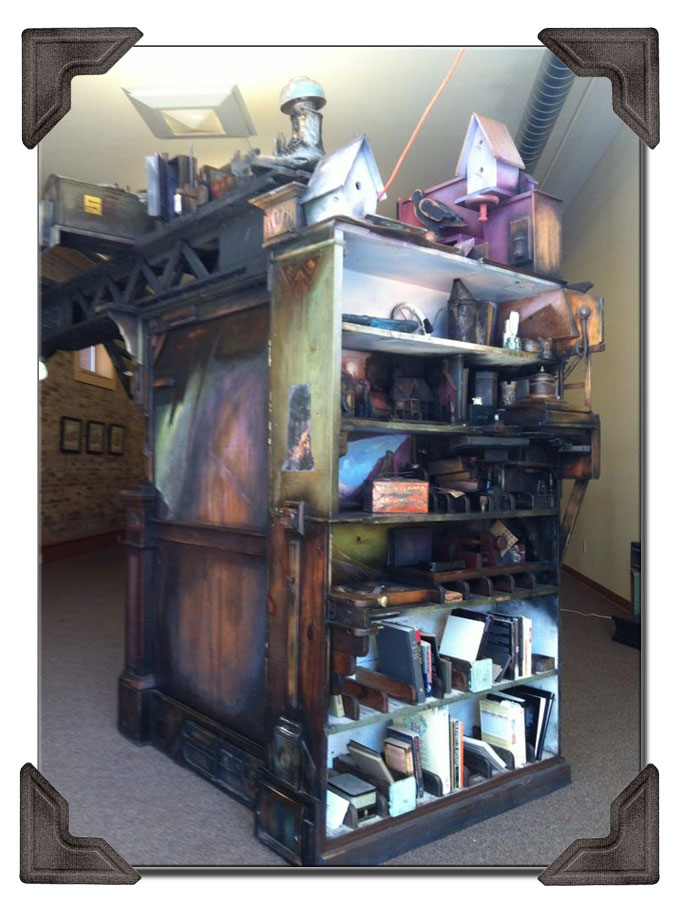

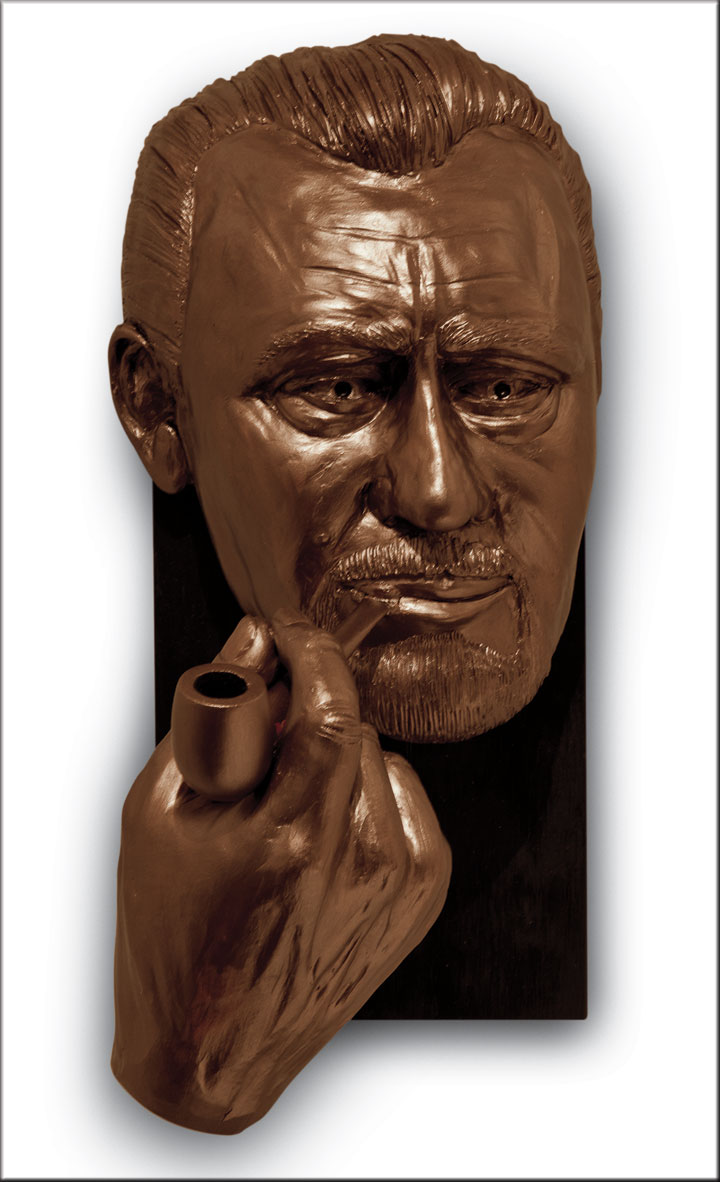

I mention Bruce Ariss because, as a latecomer to Huckleberry Hill, I lived in the house next to his, and he was the neighbor I knew best. Like many artists in the 1930s, his paintings depicted the lives of the people in the streets, on the farms, and in the factories of Pacific Grove, Salinas, and Monterey, California. A university graduate and champion collegiate boxer, he was a jack of all trades: painting, writing, editing, acting, directing, and more. Also, he was a passionate builder. He’d purchased three lots on the Hill, and he indicated that his plan was to eventually cover every available inch with a single house. The home be built was one of the first on Huckleberry Hill, and as his family grew, so did his house. Created more or less as he went along, it was not a straightforward house. John Steinbeck was to say to him one day, “Yours is an achievement over modern architecture.”

There were any number of potters living on Huckleberry Hill, and on those occasions when their creations met with disaster in the kiln, Bruce was there to collect the broken bits. From them he constructed colorful mosaics. And having an abundance of the shards on hand, he conjured up the idea of putting a soaking-pool in the middle of his front room. He began by digging a circular hole about eight feet in diameter and close to three feet deep, placing it just in front of his large stone fireplace. During the cementing process, he carefully added the potters’ bits and pieces to create a colorful mosaic tub, making sure there were no sharp edges. When it was finished he filled it with water from a garden hose. It tested well. “Never warm, but always invigorating”—that was how Bruce described the pool to me.

One day, Bruce and his “bride”—as he always referred to his wife Jean— were trying out the pool with Carol and John Steinbeck and a couple of other Huckleberry Hill people. Some were in the water and some were stretched out on blankets around it, enjoying the afternoon, when there was a weak knock at the Ariss door. That was very odd, for nobody knocked on the Ariss door: anyone and everyone simply walked in.

“Come in,” someone hollered, and a man entered. He was a small man, a gentle-looking fellow with wire-rim glasses, very properly dressed in a suit and tie. He politely removed his hat. Most of those lounging around the pool immediately recognized him as the overseer of their WPA work in Salinas. He was their boss, and he’d driven his rickety old Ford to Monterey to find out why no one from the Hill had shown up for work that day.

Stepping through the door, the man drew up short noticing that, apart from himself, there wasn’t a single soul in the room with so much as a stitch of clothing on. He looked down at his hat in his hands and began mumbling—something about the work that had to be done in Salinas, about his duty as supervisor, about his just checking to see . . . .

“Well, look, I’m sorry, I didn’t know . . . ah, we’ll talk about that when I see you in Salinas tomorrow,” he said, directing his words at no one in particular and preparing to make a hasty departure.

“We can talk now if you like,” Bruce replied. “I know you’ve had a warm, dusty drive over. You might as well take off what you’re wearing and get in and cool yourself off. And here,” he said, holding up a gallon jug. “There’s plenty of this, help yourself.”

The quiet little man lifted his head, looked around the room at the glistening bodies, then smiled. “Yeah, sure,” he said, and in a flash he was out of his attire, dangling his feet in the water and reaching for the jug of wine.