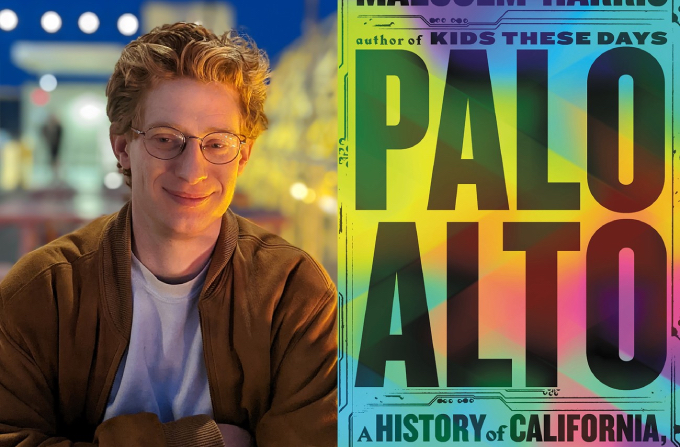

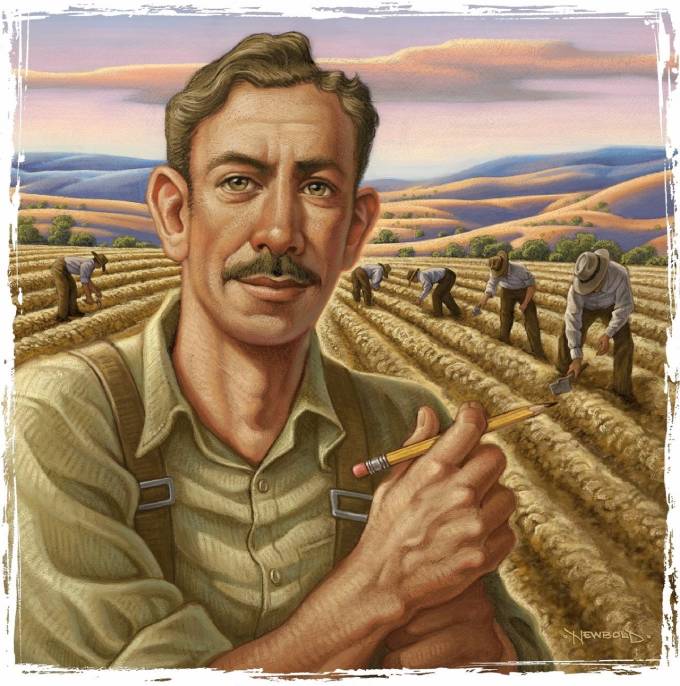

John Steinbeck shadows the world of Palo Alto like a superannuated ghost. The subtitle of Malcolm Harris’s new nonfiction bestseller—A History of California, Capitalism, and the World—offers the first hint of the haunting, followed by references to the Joads in Harris’s text and criticism of Steinbeck’s support for the Vietnam war in a testy footnote. Although Steinbeck rejected Marxist thinking, Harris doesn’t, and Harris’s critique of what Leland Stanford wrought in starting Steinbeck’s alma mater builds on Steinbeck’s version of the school’s spirit in East of Eden, where Aron, restless and unhappy, drops out of Stanford as Steinbeck did in real life.

Harris’s note on Steinbeck’s non-pacifism about Vietnam is worth quoting, particularly in the context of Ukraine, where pacifism and progressives have parted ways:

Harris’s note on Steinbeck’s non-pacifism about Vietnam is worth quoting, particularly in the context of Ukraine, where pacifism and progressives have parted ways:

Also presumed progressive based on his earlier work, Steinbeck was rabidly pro-war, and he turned himself into a military pundit. He even sent the White House a letter suggesting the Defense Department develop napalm grenades—American boys were already being trained to throw baseballs. He proposed to name the weapon the “Steinbeck super ball.” His letter was forwarded to the Department of Defense.

Malcolm Harris is young. So was John Steinbeck IV when he was presented by his father at the White House before being shipped out to Vietnam 60 years ago. Later the son slammed the father’s hypocrisy about drugs, on display during a 1966 visit, along with the hankering for high-tech weaponry cited by Harris. Unfair to Palo Alto’s superannuated ghost? When Steinbeck was young he might have made the same observation about the man he became.