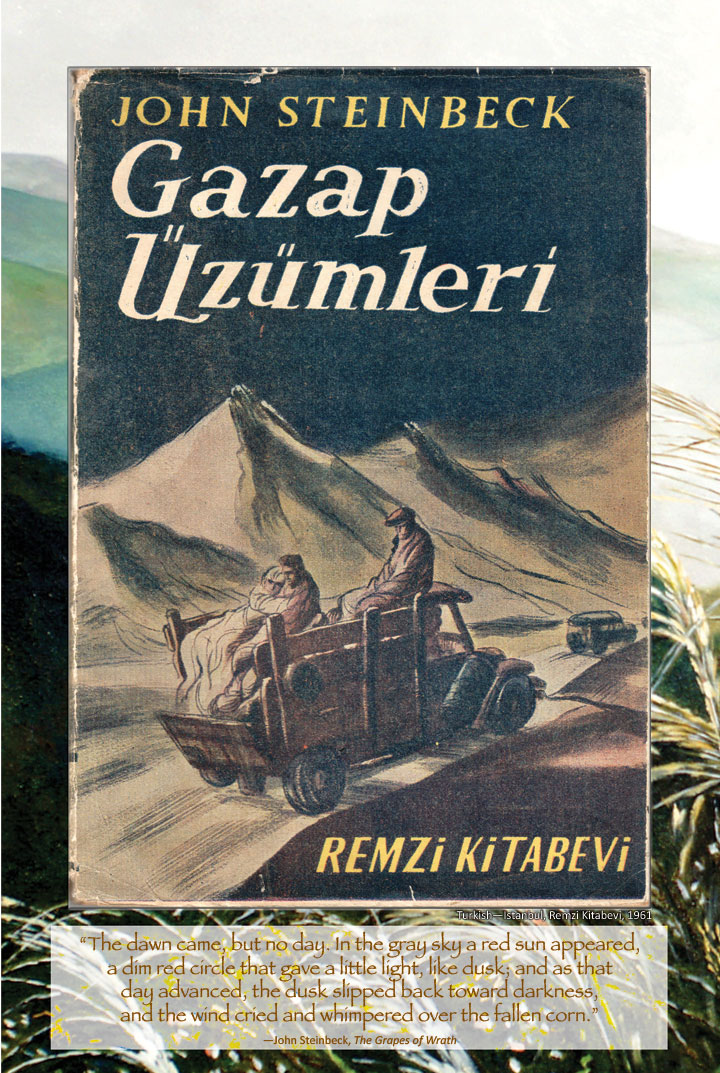

Year-end book lists may be boring, but one outlet’s pick for editor’s favorite in 2019 surprised fans familiar with John Steinbeck’s bumpy treatment by religiously-minded reviewers. Catholic News Agency, an affiliate of Eternal Word Television Network in Denver, Colorado, chose The Moon Is Down for reader attention in a December 31 round-up that includes a French priest’s commentary on the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas, A Testimonial to Grace by American Cardinal Avery Dulles, and Three to Get Married by “not-so-soon-to-be-blessed Fulton Sheen,” the photogenic philosopher-bishop who hosted the popular TV show Life Is Worth Living in the 1950s. (CAN’s deputy editor-in-chief, Michelle La Rosa, paired Steinbeck’s 1942 novella-play with a 1990 novel, The Remains of the Day, by Nobel Laureate Kazuo Ishiguro.)

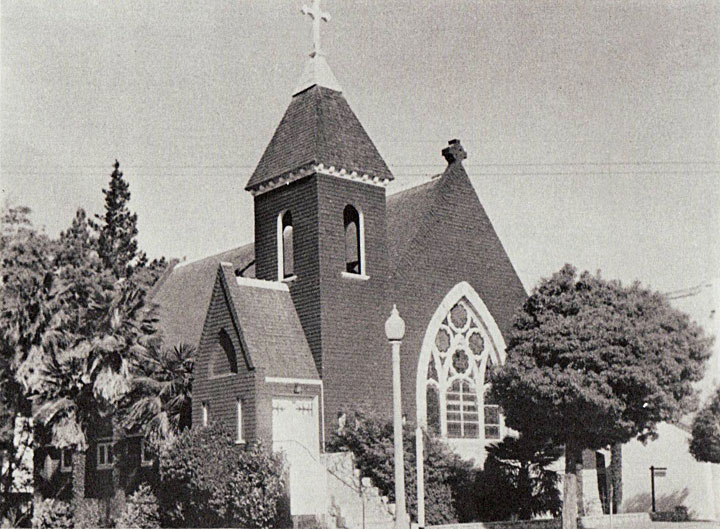

Photo courtesy Catholic Herald/Catholic News Agency.