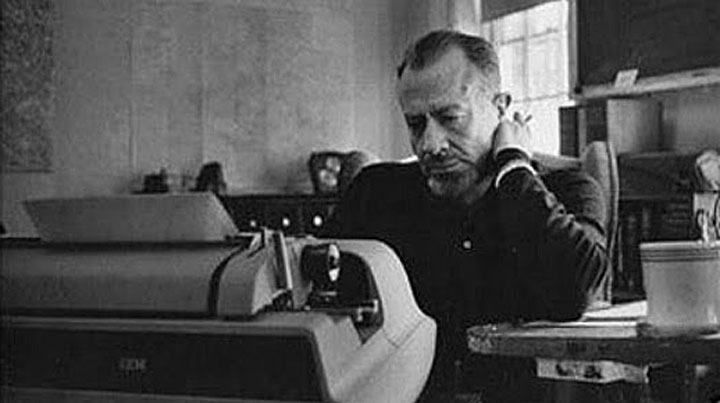

It’s doubtful either Donald Trump or the minority of Americans who just elected him ever read The Winter of Our Discontent, John Steinbeck’s prophetic fiction about public and private corruption in America 60 years ago. But for fans of the novel the parallels with our winter of discontent today are troubling. Cheating and self-dealing, inequality and incivility, anti-immigrant hatred and hysteria—is the USA less or more selfish today than it was when Steinbeck wrote his cautionary tale? For Donald Trump and his fans among America’s fraction-of-one-percent, personal profit is the golden rule and goodness can measured in tax cuts and capital gains. Add one word to the line from Richard III quoted in Steinbeck’s title—“Now is the winter of our discontent/Made glorious summer by this sun of New York”—and Shakespeare’s metaphor for an English tyrant’s mood aptly expresses the ardor felt by the Trumpettes of Mar-a-Lago, the palatial club in Palm Beach where Trump now holds winter court. I don’t know if John Steinbeck visited Mar-a-Lago. or encountered Donald Trump before he died, but I’ve had the pleasure of both and I’m pretty sure Steinbeck would take a very dim view.

John Steinbeck’s View of Donald Trump and Mar-a-Lago?

Before I moved to California and discovered Steinbeck Country I lived in West Palm Beach, where I ran a prominent nonprofit and played the organ at St. Edward’s Catholic Church, “the Kennedy church,” in Palm Beach. Once I substituted at Bethesda-by-the Sea, the Episcopal church where Trump reportedly received applause from attendees on Christmas Eve. I knew Ralph Wolfe Cowan, the artist who painted the Dorian Gray-like portrait of Trump shown in the lead photo of this post. My home in West Palm Beach wasn’t far from the bridge connecting with Palm Beach near Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump’s spacious domain, so named because it stretches from Lake Worth to the Atlantic. I passed by often on my way to church, and I was a luncheon and gala guest on those occasions when doing my job entailed hobnobbing.

It’s even possible I toured Mar-a-Lago before Donald Trump, who bought it at a discount from descendants of Post cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post in 1985. A year or so earlier a friend of mine arranged for a private look-see at the estate where Post entertained lavishly when John Steinbeck was alive. By the 1980s the mansion’s faded interior resembled Norma Desmond’s living room in Sunset Boulevard—aging, abandoned, populated by the ghosts of parties and partners past—and John Kennedy was the only ex-president with a known Palm Beach address. To fill this gap, Post willed Mar-a-Lago to the government as a presidential retreat when she died. But the property lies under the flight path of Palm Beach airport, adding to security issues, and before Trump came along the Palm Beach social scene had attracted few of Kennedy’s successors. Johnson wasn’t the Palm Beach type, Nixon and Ford and Reagan enjoyed Walter Annenberg’s hospitality in Palm Springs, and the George H.W. Bushes had close ties to the old money on Jupiter Island, a less pretentious winter enclave an hour north of Palm Beach.

It’s even possible I toured Mar-a-Lago before Donald Trump, who bought it at a discount from descendants of Post cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post in 1985. A year or so earlier a friend of mine arranged for a private look-see at the estate where Post entertained lavishly when John Steinbeck was alive. By the 1980s the mansion’s faded interior resembled Norma Desmond’s living room in Sunset Boulevard—aging, abandoned, populated by the ghosts of parties and partners past—and John Kennedy was the only ex-president with a known Palm Beach address. To fill this gap, Post willed Mar-a-Lago to the government as a presidential retreat when she died. But the property lies under the flight path of Palm Beach airport, adding to security issues, and before Trump came along the Palm Beach social scene had attracted few of Kennedy’s successors. Johnson wasn’t the Palm Beach type, Nixon and Ford and Reagan enjoyed Walter Annenberg’s hospitality in Palm Springs, and the George H.W. Bushes had close ties to the old money on Jupiter Island, a less pretentious winter enclave an hour north of Palm Beach.

Palm Beach prejudice presented another problem. Kennedy wasn’t welcome everywhere, even as president, and top-tier social clubs like the one across the road from Mar-a-Lago excluded Catholics and Jews from membership as recently as my time. To his credit, Donald Trump thumbed his nose at this tradition when he opened Mar-a-Lago Club for those with sufficient cash and cachet, regardless of race or religion, in 1995. As a marketing strategy his open-door policy was a winner, attracting socialites and business leaders and making Mar-a-Lago a popular venue for black-tie charity events. Trump’s inauguration committee may be having trouble signing talent, but name entertainers like Vic Damone loved playing Mar-a-Lago, and the evening I spent chatting with Diahann Carroll, Vic’s wife at the time, is my warmest memory of the place. Vanity Fair covered Mar-a-Lago favorably almost from the start, though the tone changed after the editor of the magazine described Trump as a “short-fingered vulgarian.” (“How Donald Trump Beat Palm Society and Won the Fight for Mar-a-Lago“ was a source of images for this post.)

Palm Beach prejudice presented another problem. Kennedy wasn’t welcome everywhere, even as president, and top-tier social clubs like the one across the road from Mar-a-Lago excluded Catholics and Jews from membership as recently as my time. To his credit, Donald Trump thumbed his nose at this tradition when he opened Mar-a-Lago Club for those with sufficient cash and cachet, regardless of race or religion, in 1995. As a marketing strategy his open-door policy was a winner, attracting socialites and business leaders and making Mar-a-Lago a popular venue for black-tie charity events. Trump’s inauguration committee may be having trouble signing talent, but name entertainers like Vic Damone loved playing Mar-a-Lago, and the evening I spent chatting with Diahann Carroll, Vic’s wife at the time, is my warmest memory of the place. Vanity Fair covered Mar-a-Lago favorably almost from the start, though the tone changed after the editor of the magazine described Trump as a “short-fingered vulgarian.” (“How Donald Trump Beat Palm Society and Won the Fight for Mar-a-Lago“ was a source of images for this post.)

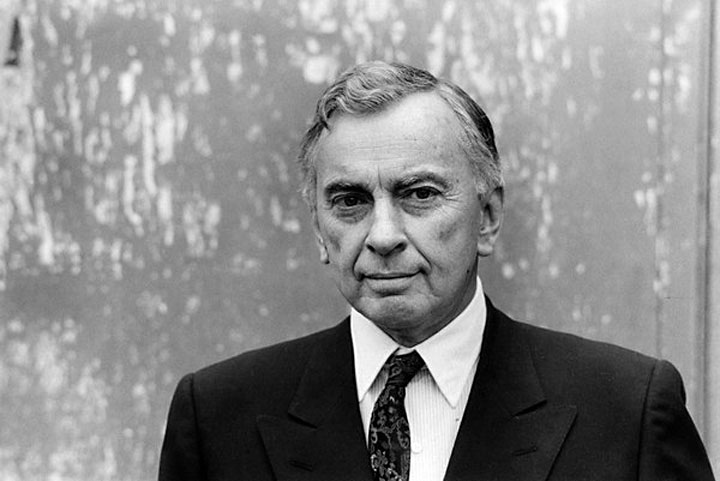

In 2003 my organization was celebrating its 25th anniversary when the publisher and a retinue from Vanity Fair flew to town in preparation for an expose of Palm Beach social mores. One of the writers in the group—the late Christopher Hitchens, a regular contributor to Vanity Fair—invited me to tag along when a Republican billionaire with a household name hosted dinner at a Palm Beach club that still banned Jews. Rather late in life Hitchens had learned that his maternal grandmother was Jewish, a topic of conversation as we waited outside the club, so I suggested that he ask for a kosher menu once we were inside and seated for dinner. The next day I got a call from the head of the Palm Beach cultural venue where my organization’s anniversary event was about to be held. It happened that his board chairman was an officer of the club—a thin-skinned millionaire who learned, almost instantly, about our quiet indiscretion the night before. I wrote the requisite letter of apology and agreed to keep my mouth shut about the incident, but Christopher seemed gratified when I reported the result to him. He said it proved our point perfectly.

In 2003 my organization was celebrating its 25th anniversary when the publisher and a retinue from Vanity Fair flew to town in preparation for an expose of Palm Beach social mores. One of the writers in the group—the late Christopher Hitchens, a regular contributor to Vanity Fair—invited me to tag along when a Republican billionaire with a household name hosted dinner at a Palm Beach club that still banned Jews. Rather late in life Hitchens had learned that his maternal grandmother was Jewish, a topic of conversation as we waited outside the club, so I suggested that he ask for a kosher menu once we were inside and seated for dinner. The next day I got a call from the head of the Palm Beach cultural venue where my organization’s anniversary event was about to be held. It happened that his board chairman was an officer of the club—a thin-skinned millionaire who learned, almost instantly, about our quiet indiscretion the night before. I wrote the requisite letter of apology and agreed to keep my mouth shut about the incident, but Christopher seemed gratified when I reported the result to him. He said it proved our point perfectly.

Like John Steinbeck, a writer he admired, Christopher Hitchens was politically astute, egalitarian, and courageous under fire from bullies, Left or Right. Like Steinbeck, he supported America’s pursuit of an unpopular war (in Hitchens’s case, Iraq; in Steinbeck’s, Vietnam) and bravely paid the price. Like Steinbeck, he distrusted power, disliked braggadocio, and detested xenophobia, insult, and incitement to mob violence of the kind seen more than once during Donald Trump’s campaign for president. Roy Cohn, the McCarthy-era lawyer who taught Trump how to play New York hardball, was anathema to Hitchens, as he’d been to Steinbeck when The Winter of Our Discontent was written. The odious combination of compulsive mendacity, obsessive opportunism, and pathological aggression that repelled Steinbeck advanced Cohn’s career and attracted clients. One of them was Donald Trump, the billionaire developer described by Hitchens in 1997 as a “bankrupt real-estate monarch [who] can treat the skyline as his own without any hint of a nasty creditors’ meeting at any of his numerous and lenient banks.” Trump’s Palm Beach ascendancy might have amused Hitchens. But I think it would offend Steinbeck, who ridiculed small-town ambition and conspicuous consumption in The Winter of Our Discontent.

Like John Steinbeck, a writer he admired, Christopher Hitchens was politically astute, egalitarian, and courageous under fire from bullies, Left or Right. Like Steinbeck, he supported America’s pursuit of an unpopular war (in Hitchens’s case, Iraq; in Steinbeck’s, Vietnam) and bravely paid the price. Like Steinbeck, he distrusted power, disliked braggadocio, and detested xenophobia, insult, and incitement to mob violence of the kind seen more than once during Donald Trump’s campaign for president. Roy Cohn, the McCarthy-era lawyer who taught Trump how to play New York hardball, was anathema to Hitchens, as he’d been to Steinbeck when The Winter of Our Discontent was written. The odious combination of compulsive mendacity, obsessive opportunism, and pathological aggression that repelled Steinbeck advanced Cohn’s career and attracted clients. One of them was Donald Trump, the billionaire developer described by Hitchens in 1997 as a “bankrupt real-estate monarch [who] can treat the skyline as his own without any hint of a nasty creditors’ meeting at any of his numerous and lenient banks.” Trump’s Palm Beach ascendancy might have amused Hitchens. But I think it would offend Steinbeck, who ridiculed small-town ambition and conspicuous consumption in The Winter of Our Discontent.

Steinbeck’s California Dreads What Palm Beach Celebrates

I am unacquainted with the four Trumpettes who posed for Vanity Fair in front of Ralph Cowan’s painting of Donald Trump. But I recognized names from the past when I read reports about holiday festivities at Mar-a-Lago. An outspoken Trumpette quoted by national media outlets once worked for the Democratic county commissioner from West Palm Beach. On New Year’s Day the Palm Beach daily newspaper published an admonishing letter to readers in which she promised that “President-elect Trump will make us financially secure again” and described “the days of massive government waste and corruption” as a thing of the past caused (presumably) by Democrats. Today, more than 30 years after I first met this woman and a decade after leaving Florida for California, I feel about Donald Trump’s Palm Beach as John Steinbeck felt about Salinas, his home town. I’m grateful for the memories but sad for the “dear little town” I used to know. As Mar-a-Lago celebrates and Washington gets ready, the winter of our discontent grows darker by the day here in his home state.

I am unacquainted with the four Trumpettes who posed for Vanity Fair in front of Ralph Cowan’s painting of Donald Trump. But I recognized names from the past when I read reports about holiday festivities at Mar-a-Lago. An outspoken Trumpette quoted by national media outlets once worked for the Democratic county commissioner from West Palm Beach. On New Year’s Day the Palm Beach daily newspaper published an admonishing letter to readers in which she promised that “President-elect Trump will make us financially secure again” and described “the days of massive government waste and corruption” as a thing of the past caused (presumably) by Democrats. Today, more than 30 years after I first met this woman and a decade after leaving Florida for California, I feel about Donald Trump’s Palm Beach as John Steinbeck felt about Salinas, his home town. I’m grateful for the memories but sad for the “dear little town” I used to know. As Mar-a-Lago celebrates and Washington gets ready, the winter of our discontent grows darker by the day here in his home state.