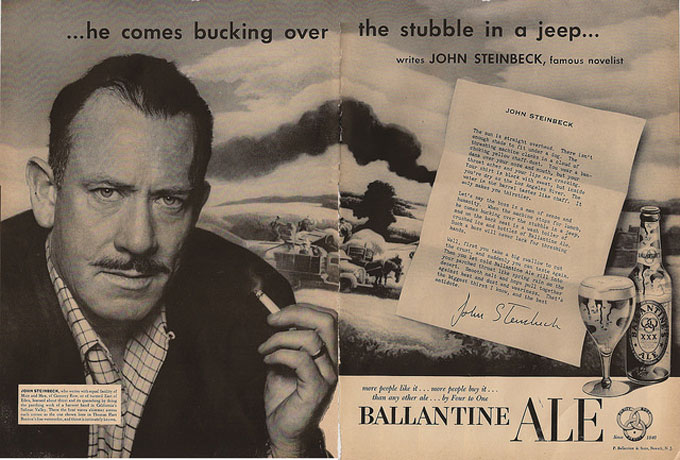

In May of 1942, three years after writing The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck wanted to arm himself with a Colt automatic for “self-protection.’’ He was living in New York, and the State of New York said he must get a license—something the recent 18-year old elementary shooter in Uvalde, Texas didn’t have to do.

New York said Steinbeck needed four character witnesses to get his license. It didn’t matter that The Grapes of Wrath had won the Pulitzer Prize, or that its author was famous. And no making things up: each character reference, the state demanded, “must be personally signed.” The actor Burgess Meredith and the artist Henry Varnum Poor added their names to John Steinbeck’s New York application. A veterinarian named Morris Segal and actress Sally Bates Lorentz also signed. Doing so took some courage. Steinbeck wasn’t politically popular, and his character witnesses had their own public careers. Could the Uvalde, Texas killer have found four witnesses to vouch for his 18-year old character?

But New York wasn’t satisfied with willing or even well-known character witnesses. It had another question for John Steinbeck: “Have you ever had a pistol license?” Steinbeck replied that he had, in 1938. Presumably he obtained that license in California. And, came another query, had he ever had a license application disapproved? Steinbeck replied, “No.” Well then, the state continued, had he ever had a gun license revoked or cancelled? “No” again. Steinbeck was then “sworn” that all his statements were true and that “the photo attached hereto was taken within thirty days prior to the date of his application.”

In short, the State of New York in 1942 wanted to know just who in the hell they were allowing to carry a firearm within its borders. Now, 80 years later, should Texas and other states think seriously about doing what New York did then, particularly when it comes to military-style weapons like the ones used to kill 19 schoolchildren and two teachers?

The Winchester Rifle John Steinbeck Gave His First Wife

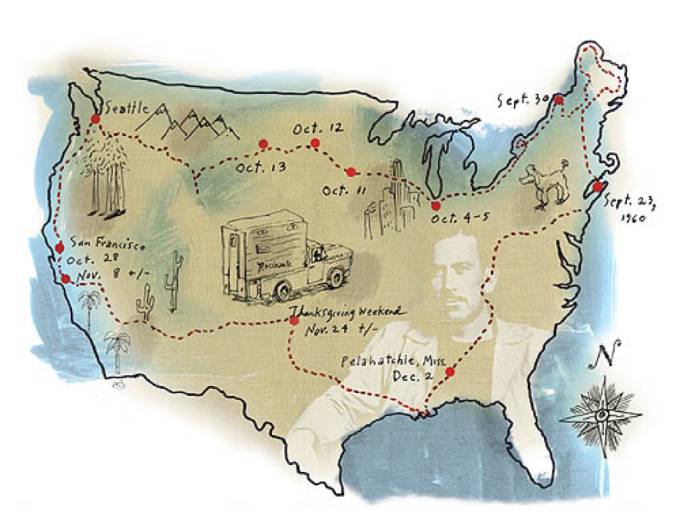

I bring this up now because of the Uvalde, Texas massacre and the renewed debate about gun control in America, but also because I am looking at a rifle that John Steinbeck and his wife Carol owned and handled—another indicator that guns were a part of Steinbeck’s life from the 1930s to his death in 1968. The rifle is a Winchester Model 60-22, and Steinbeck gave it to Carol when they were married. Eventually it descended to Carol’s stepdaughter, Sharon Brown Bacon.

“I inherited the Steinbeck rifle from my father, William B. Brown, who was married to Carol Henning (Steinbeck) Brown for many years,” Bacon explains. “Carol, my stepmother, was John Steinbeck’s first wife and predeceased my father,” she continued. “I have always known the rifle to belong to Carol and that she was given it by John after they were married in 1930. At that time they were living in Los Gatos . . . . She used it, in her words, ‘for protection’ while alone there, and later at her home in Carmel Valley.”

Why did Steinbeck feel the need for a gun at all? A woman in Salinas told me years ago that she witnessed a man threatening Steinbeck with a gun in a Salinas park for what he was writing about their town in the run up to The Grapes of Wrath. The woman said she felt traumatized and thought Steinbeck probably did, too. This could be the origin story of the gun license Steinbeck obtained in 1938.

In 1946 and living in New York, Steinbeck wrote to a California friend, a motorcycle cop named George Dovolis, in care of the Monterey Police Department. He asked if Dovolis could ship him a “little thirty-eight,’’ which Steinbeck said he needed “for house protection.” We know Steinbeck had guns stowed away in Monterey or Pacific Grove because he wrote Dovolis, “I am very grateful to you for taking care of my guns while I have been away.” By 1948 Dovolis had transitioned to real estate, and Steinbeck wrote that he wanted to make him a gift of a gun in gratitude for past help.

In 1949 Dovolis, who would go on to found the still-flourishing Boys and Girls Club of Monterey County, returned the favor and shipped “1 box guns’’ to Steinbeck via Railway Express. So until May of that year, at least, guns were still on John Steinbeck’s mind—and about to arrive on his doorstep.

Thankfully, at least as far as we know, they were never used in self-defense. If one of them had been, it’s safe to assume it would have been properly licensed, including the signatures of character witnesses willing to testify that Steinbeck was a person who could be trusted to do the right thing. Perhaps it’s time for character witnesses to be brought back into America’s ongoing gun debate, post-Uvalde.