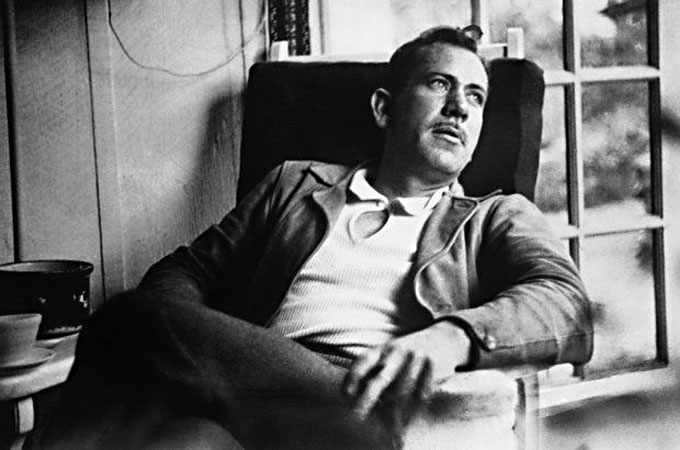

If Gavin Jones had been a professor there 100 years ago, would John Steinbeck have stayed at Stanford University long enough to finish? Probably not, according to Jones, who addressed the fraught subject of Steinbeck@Stanford at the Stanford University Library on January 30. Jones—who holds the Frederick P. Rehmus Family Chair in Humanities in the Department of English—spoke to a capacity crowd of 200 at the evening event, which was sponsored by the Stanford Historical Society and included a pop-up exhibit from the library’s collection of Steinbeck manuscripts and memorabilia. Credited with contributing to the revival of campus interest in Steinbeck, who enrolled intermittently between 1919 and 1925, Jones used examples of Steinbeck’s early writing to show how Stanford’s emphasis on creativity, collaboration, and interdisciplinary learning shaped the character, context, and content of works like To a God Unknown and Cannery Row—manuscripts of which, in Steinbeck’s hard-to-read hand, were on display at the event. Although he left without earning a diploma and refused to accept an honorary degree, “Stanford was always on his mind,” said Jones. Assuming “the mythology of a misfit” early in his career, Steinbeck was a life-long experimenter whose insights into ecology, empathy, and eugenics—all shaped by Stanford—were, Jones added, ahead of their time and set him apart from literary figures like William Faulkner, who dropped out of Old Miss, and Ernest Hemingway, who skipped college to work as a reporter.

Fall 2019 Steinbeck Review Reconsiders John Steinbeck

The Fall 2019 issue of the journal Steinbeck Review, a biannual publication of Penn State Press in cooperation with the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, is now available online and in print. Contents include essays on aspects of John Steinbeck’s life and work as a proto-ecologist and internationalist viewed from a contemporary perspective; the publishing history of Steinbeck’s books in the former Iron Curtain countries of Eastern Europe; and the challenges of teaching Steinbeck to students who may be better versed in the #MeToo movement than the progressive labor movement that preoccupied Steinbeck’s interest and writing in the 1930s. Also included in the Fall 2019 issue are book reviews, announcements, and a summary of Steinbeck news since the summer.

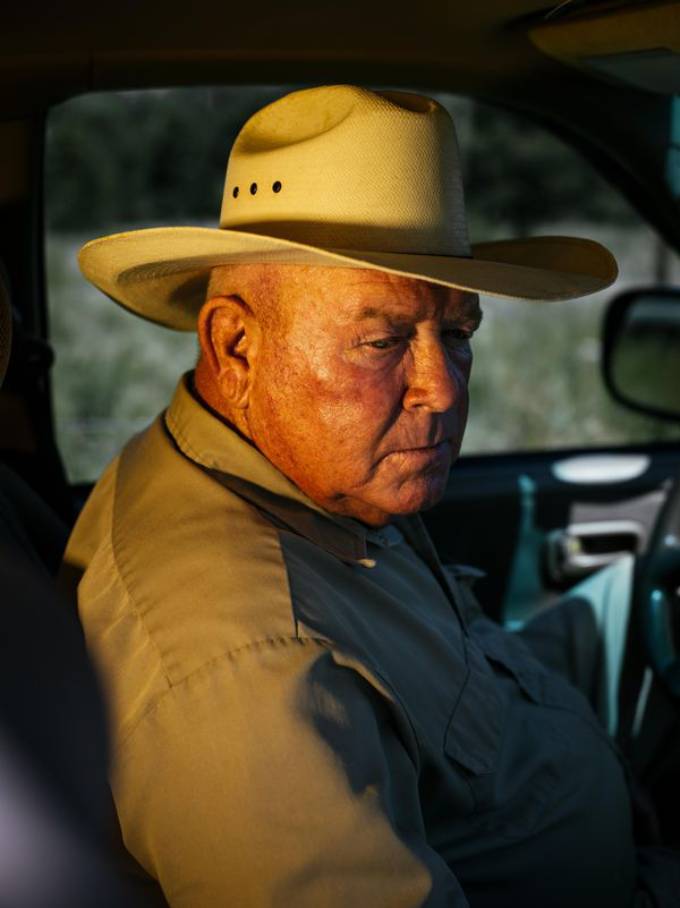

Before The Grapes of Wrath, Anger in Seminole County

Richard Grant, the British travel writer who plumbed Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez in the September 2019 issue of Smithsonian Magazine, now sheds light on The Grapes of Wrath—without mentioning Steinbeck’s name—in the October issue of the same magazine. “Rebellion in Seminole County” recounts the populist revolt that swept through parts of the rural South in the environment and aftermath of America’s entry into World War I. In 1915 there were more registered members of the Socialist Party in Oklahoma than New York, and in 1917 a group of Seminole County, Oklahoma tenant farmers who looked and sounded like Tom Joad joined something called the Green Corn Rebellion, an armed insurrection aimed at local draft boards, big-city bankers, and the interventionist Wilson administration in Washington. Among the organizers who eventually served jail time were two of the uncles of Ted Eberle, a former Seminole County commissioner who was interviewed by Grant for the article. “They thought they could overthrow the government and avoid the draft,” said Eberle, though confiscatory interest rates, plummeting land ownership, and corporate-capitalist war profiteering were also factors in the movement. Steinbeck was a curious teenager who read voraciously and thought deeply when blood was spilled in the name of social justice in Oklahoma 100 years ago. Contemporary readers may be forgiven for making a notional connection between the Oklahoma back story of The Grapes of Wrath and the nugget of Oklahoma history brought to light by Richard Grant in the October issue of Smithsonian Magazine, where a brilliant freelancer has enlightened students of Steinbeck for the second time in two months—this time without even mentioning Steinbeck’s name.

Photograph of Ted Eberle by Trevor Paulhus courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine.

Cannery Row, Sea of Cortez Still Making Waves—On Both Sides of the Ocean—in 2019

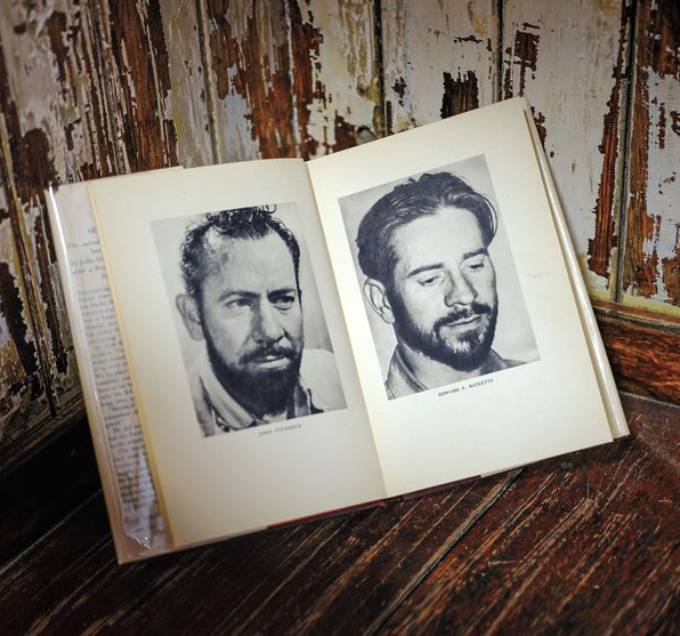

Anticipating the 80th anniversary of John Steinbeck and Edward Ricketts’s expedition to the Sea of Cortez, and the 75th anniversary of the publication of Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row, new profiles by or about a pair of writers born in England brilliantly reflect the role played by Steinbeck, Ricketts, and their free-range relationship in marrying literary imagination with marine biology to create modern ecological consciousness.

“John Steinbeck’s Epic Ocean Voyage Rewrote the Rules of Ecology”—a thoroughly researched and well-written feature by Richard Grant in the September 2019 issue of Smithsonian Magazine—recounts the 1940 journey that resulted in Sea of Cortez, the 1941 book co-authored by Steinbeck and Ricketts, and the ambitious project to restore The Western Flyer, the boat they used for their “voyage of discovery” to the waters and shores of Baja California. The fact-filled text by Grant, a British journalist based in Mississippi, is creatively complemented by photographs (like the one above) by Ian C. Bates, who lives near Port Townsend, Washington, where work on The Western Flyer continues, with an eye toward relaunch off Cannery Row in 2020.

How Cannery Row Became California

The British literary naturalist and neurologist Oliver Sacks died from cancer in August of 2015, but the prolific polymath’s debt to Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the Steinbeck-Ricketts collaboration is detailed in a pair of books published in the first half of 2019. Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales, the “final volume” of essays on life, death, and Planet Earth by Sacks (who published 15 books, including Musicophilia and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) contains this paragraph about coming to Steinbeck country from Canada in 1960:

I was twenty-seven. I had arrived in North America a few months before and started out by hitchhiking across Canada, then down to California, which I had been in love with since I was a fifteen-year-old schoolboy in postwar London. California stood for John Muir, Muir Woods, Death Valley, Yosemite, the soaring landscapes of Ansel Adams, the lyrical paintings of Albert Bierstadt. It meant marine biology, Monterey, and “Doc,” the romantic marine biologist figure in Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

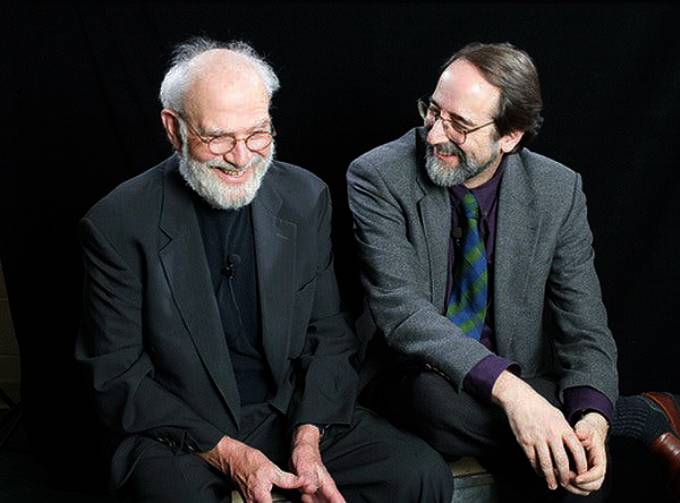

How Melville and Steinbeck Became Bookends

By 1982 Sacks had achieved fame as a medical renegade with literary genius for his book Awakenings, a suspenseful history of the set of post-encephalitic parkinsonian patients temporarily unfrozen by experimental L-dopa at the Bronx psychiatric hospital where Sacks worked, not without controversy, after he moved to New York. In 1982 Sacks was accompanied by the American journalist Lawrence Wechsler (at right in photo with Sacks) on a trip home to England for a New Yorker magazine profile of Sacks that never appeared. And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?—Wechsler’s memoir of the 35-year friendship that developed between the two men—records the following exchange, about influences, after a visit with Sacks’s 90-year-old father, a genial general practitioner in London who introduced his four precocious sons early (three became doctors) to the pleasures of science and reading:

Later, conversation with Oliver reverts to his childhood and school years. I ask him what sorts of books captivated him as a youth.

“Moby-Dick,” he replies, without a moment’s hesitation. “What can you say about Moby-Dick? There’s Shakespeare and there’s Moby-Dick and that’s that.

“We liked Cannery Row and Sea of Cortez, for the marine biology.” (Funny that, as bookends go: Moby-Dick and Cannery Row.)

Shakespeare, Melville, and marine biology also fired John Steinbeck’s mind. As bookends go, Oliver Sacks and Smithsonian Magazine make splendid specimens of the exultation expected in 2020 around Sea of Cortez, Cannery Row, and the marriage of marine biology and literary imagination—on both sides of the Atlantic.

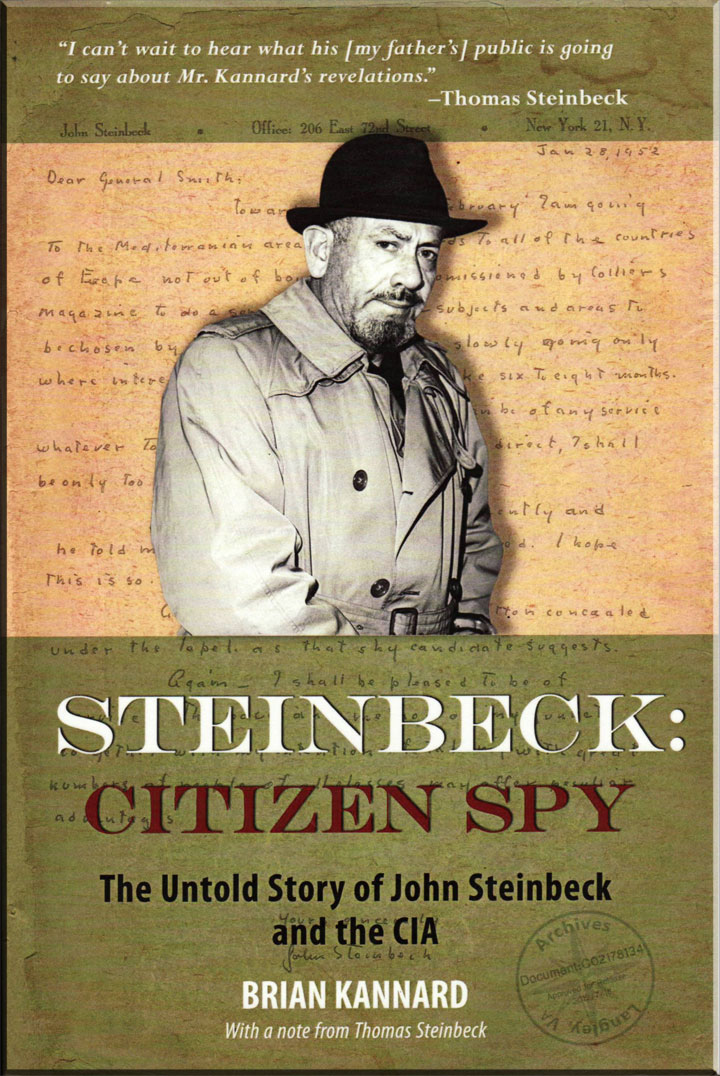

Christopher Dickey Asks: Was John Steinbeck a CIA Informant in Paris in 1954?

Was John Steinbeck acting as a CIA informant in Paris the summer he wrote the satirical short story for Le Figaro, published in English for the first time in the current issue of The Strand, about a haughty French chef and his hyper-finicky cat? That’s the question raised in a provocative Daily Beast piece by Christopher Dickey, the Daily Beast’s Paris-based world-news editor. Working his way to a firm maybe, Dickey quotes John Steinbeck’s contemporaneous correspondence with his New York agent, Elizabeth Otis, and Thom Steinbeck’s eye witness account—first cited by Brian Kannard in his 2013 book Steinbeck: Citizen Spy—of daily visits to the Steinbeck’s residence at 1 Avenue de Marigny by a man from the U.S. embassy with an attaché case. The son of a famous father, like Thom Steinbeck, Christopher Dickey is a frequent contributor to Foreign Affairs, Vanity Fair, The New York Times, MSNBC, CNN, France 24, BBC TV, and Al Jazeera.

The Music of John Steinbeck

I was recently asked to consider writing an essay about Steinbeck’s short novel The Pearl to be included in a text series for secondary and undergraduate English education. Frankly The Pearl wasn’t one of my favorite Steinbeck books, and I couldn’t imagine I would be able to come up with 20 pages on the short novel. But the more I reread it, the more the subject of the Song of the Pearl kept nudging my interest. I became curious about Steinbeck’s specifying a “song” as opposed to a musical note, chord, or phrase. I knew he was interested in classical music, and I believed his choice of the word “song” was important to the story. But the publisher’s formatting specifications were overwhelming and I couldn’t decide how to reduce the content to fit within the length requirements, so I decided to publish it elsewhere. I believe doing so is important to my personal mission to support the practical and scientific psychology of Carl Jung and William James as it was deftly applied by John Steinbeck in his fiction and non-fiction. The Song of the Pearl is about personal styles, levels of maturity, attitudes, and how such things influence individual perception, judgment, decision-making, problem-solving, and social bodies like the small indigenous coastal village of the central character in the novel.

Vote Early and Vote Often for The Grapes of Wrath in 2018

The Grapes of Wrath, the book John Steinbeck finished writing in time to vote for Culbert Olson as Governor of California in 1938, is still running strong with readers, despite naysayers like the Los Gatos Republican who wrote a counter-novel, now forgotten, in 1940. This year The Grapes of Wrath has competition in the race for Great American Read—a project of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with support from the Anne Ray Foundation, to encourage reading by allowing anyone over 12 to vote early and vote often for his or her favorite from a list of 100 novels, all in English, that polled well with viewers. The contest would probably appall Steinbeck, a one-man, one-vote Democrat who thought popularity pageants were stupid, especially where writers were concerned. Among the books we know he read was Two Years Before the Mast, a seagoing Grapes of Wrath written in 1840 by Richard Henry Dana, the Massachusetts lawyer and reformer who coined the phrase “vote early and vote often” in a letter about election rigging in his day. Great American Read rules permit repeat voting by the same person and reward social networking to spread the word about books, 21st-century style. So get with the program. Vote early and vote often for The Grapes of Wrath.

Test Drive John Steinbeck’s America and Leave Feedback

Early in 1938, as Steinbeck began writing The Grapes of Wrath at his home in the mountains, he was nervous about doing justice to an American tragedy unfolding in real time: the flight of desperate farm families from the Dust Bowl states of Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas to the Promised Land of California. “I’m trying to write history while it is happening,” he explained in a letter to his agent Elizabeth Otis, “and I don’t want to be wrong.” In the spring semester of 2017 I taught a course on John Steinbeck’s America that showed how right he was. It resulted in a new author website devoted to the world that John Steinbeck critiqued and created.

Twenty-three upperclassmen and two graduate students (one from Poland) enrolled for the course, offered in the University of Oklahoma’s College of Arts and Sciences. They came from Biology and Psychology and Letters as well as English and History, the departments in which it was cross-listed for credit. They read a variety of John Steinbeck’s works and discussed them within the context of American history and current events. They wrote papers on Steinbeck’s travels and wartime writing, works on stage and screen, Oklahoma, and East of Eden. They created the website introduced here for the first time for your comment.

The effort had excellent support. Mette Flynt, a PhD candidate in History, helped tighten prose, ensure accuracy in citations, and achieve consistency of language and layout. Paul Vieth, an MA student in History of Science, assisted with the Resources and Research page. Sarah Clayton—the University of Oklahoma Libraries staff member who won a national award for her innovative work with digital humanities course initiatives like this one—provided the class training in website construction using Omega, an open-source publishing platform. You can help by test driving the site and making suggestions.

Go to John Steinbeck’s America and give us your feedback in the comment box below.

Lifelong Learning Through Travels with Charley

Like most of the middle age-plus pupils in the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute classes I teach at the University of Richmond, I first read John Steinbeck’s fiction as a young adult. But I chose a work of nonfiction written by Steinbeck in middle age—Travels with Charley In Search of America—to open the course I teach in American literary classics. Before we begin, I advise those who read Travels with Charley when they were young, as I did, to disregard first impressions and read it again with fresh eyes. As Steinbeck observes at the outset of the journey, what we see is determined by how we view: So much there is to see, but our morning eyes describe a different world than do our afternoon eyes, and surely our wearied evening eyes can report only a weary evening world. You don’t even know where I’m going. I don’t care. I’d like to go anywhere. I set this matter down not to instruct others but to inform myself.

As Steinbeck observes at the outset of the journey, what we see is determined by how we view.

Later, discussing the book’s significance in middle age, we recall how we explored Steinbeck’s America in our teens and twenties—driving, and riding trains, buses, and planes; experimenting with ideas; testing the patience of people who were our parents’ and Steinbeck’s age during the turbulent decade of the sixties. For many of us, the need to experience our parents’ world through the “morning eyes of youth” was the reason we read Travels with Charley the first time around. Even in middle age, Steinbeck understood the impulse to escape: When I was very young, and the urge to be someplace else was on me, I was assured by mature people that maturity would cure this itch. When years described me as mature, the remedy prescribed was middle age. In middle age, I was assured greater age would calm my fever and now that I am fifty-eight perhaps senility will do the job . . . I fear this disease incurable.

Even in middle age, Steinbeck understood the impulse to escape.

Reading Travels with Charley in maturity gives my students renewed respect for Steinbeck’s courage in answering the call of the road by driving a fitted-up camper solo from one coast to the other, with his wife’s poodle as companion and a deep understanding that “after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.” Steinbeck’s itinerary in 1960 included destinations he visited on book tours years before—places he visited without fully experiencing them—and avoided high-speed super-highways, which were spreading like cancer across the map of post-war America. Steinbeck’s recognition that “When we get these thruways across the whole country . . . it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing” resonates with us as we recall the places we passed through along the way and reflect on the influence Travels with Charley continues to exert on how Americans think America is or was or ought to be.

We reflect on the influence Steinbeck continues to exert on how Americans think America is or was or ought to be.

All of us are amazed that Steinbeck could travel cross-country incognito until he came to Salinas, the home town he abandoned in 1925, and some identify with the sense of rejection he felt from family members and friends who failed to understand the values and ideas he expressed in the books he wrote in the 1930s. Like Thomas Wolfe, he became a stranger among his own people, though he knew better than to blame them. “Through my own efforts,” he notes, “I am lost most of the time without any help from anyone,” and he recognizes lost-ness in the people and places he encounters in Travels with Charley. A waitress has “vacant eyes” which could “drain the energy and excitement” from a room. “Some American cities are like badger holes, ringed with trash . . . surrounded by piles of wrecked and rusting automobiles [and] smothered in rubbish.” Observed firsthand, the anger of housewives protesting school desegregation in New Orleans seems inhuman and insane. “I’ve seen a look in dogs’ eyes,” he concludes, “a quick and vanishing look of amazed contempt, and I am convinced that basically, dogs think humans are nuts.”

Like Thomas Wolfe, he became a stranger among his own people, though he knew better than to blame them.

We try to avoid issues of race in class (though everyone recognizes that they still exist). As Steinbeck notes, “A dog is a bond between strangers,” and because many of us are empty-nesters, we focus instead on Steinbeck’s feelings for his dog Charley, who “loved deeply and tried dogfully,” and on the improved status of pets in his writing after Of Mice and Men. Reading or rereading Travels with Charley opens middle-aged eyes to the need for connection and companionship Steinbeck felt at a time of life when sudden loss or change—in a family or a country or a culture—can lead to alienation, loneliness, and depression. Those who think and feel after 50 will recognize the danger of despair. John Steinbeck, who made lifelong learning a creative enterprise, responded by creating an adventure for himself and us that makes Travels with Charley rewarding reading at any age.

Photo of Osher Institute for Lifelong Learning class courtesy University of Richmond.

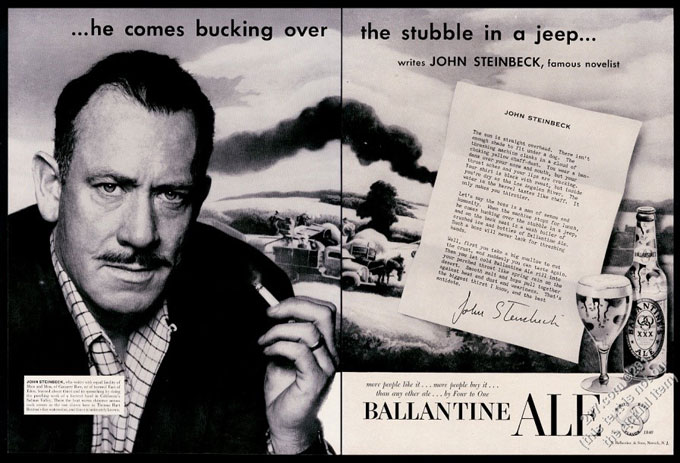

Why Cultural Appropriation Is Much Worse than Alcohol

Identity politics aside, quoting John Steinbeck out of context is an act of cultural appropriation calling for correction when the interest being served is one Steinbeck criticized in his writing. Ballantine Ale benefited from his endorsement in this 1953 advertisement, true, but the author of The Grapes of Wrath distrusted big business and condemned consumerism in Travels with Charley and The Winter of Our Discontent. “If I wanted to destroy a nation,” he confided to Adlai Stevenson in 1959, “I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy and sick.” Forbes magazine had been defending corporate power and prestige for decades when Steinbeck wrote his letter to Stevenson, and our so-called business president began his career as a serial liar by gaming his score on the magazine’s annual wealthiest-list in the 1980s. Reason enough to object to today’s cultural appropriation of John Steinbeck’s advice to budding writers by the expert who posted “How to Use Targeted Content Marketing to Gain More Customers” at the magazine’s online edition for budding entrepreneurs: “Remember that great outreach is an act of storytelling. As author John Steinbeck wrote, “Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theater, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader.” If you wanted to destroy a nation in 2018, having Donald Trump for president and Forbes magazine for literary light would be a sobering way to start.