Bedside manner works both ways. When John Steinbeck was hospitalized halfway through 1968, his doctor Denton Cox wrote on his chart, “The patient has sent me to Ecclesiastes,” a biblical book with the stoical view that the ultimate antidote for suffering is surrender. The physician followed the advice and Steinbeck was sent home, where he died in December. “What do I want in a doctor?” he asked in a letter he wrote to Cox at the beginning of their relationship: “Perhaps more than anything else—a friend with special knowledge.” Explaining his disbelief in “a hereafter” in clinical terms of “experience, observation and simple tissue feeling,” he went on to defend euthanasia, insisting “that the chief protagonist should have the right to judge his exit” when the time comes to let go and die. East of Eden, like Ecclesiastes, is a quotable book, and one medical news source says physicians should be more like Cox and pay attention to its message of empathy. A February 28, 2018 editorial in Medical News Report—a proprietary publication of Healthline Media UK Ltd.—quotes East of Eden to help contemporary healthcare professionals understand how empathy differs from sympathy, and why John Steinbeck continues to require medical attention, though of a different sort, today.

Steinbeck Review Expands Scope, Issues Call for Papers

Steinbeck Review, recently honored by listing in the international database Scopus, has expanded its purpose to specify that articles submitted for publication not only delight and instruct (à la Horace), but also illuminate issues, including the themes and problems treated in John Steinbeck’s work. This policy change reflects Steinbeck’s concern for truth and enlightenment, as well as for compassion and magnanimity, in books that warned readers of moral decline—and potential demise—in the America that Steinbeck loved. The subject of America and Americans preoccupied the writing of his final decade, and The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel, acknowledged this didactic purpose: “Readers seeking to identify the fictional people and places here described would do better to inspect their own communities and search their own hearts, for this book is about a large part of America today.”

How to Submit Papers for the Spring 2018 Issue

In addition to more traditional scholarly articles, Steinbeck Review invites the submission of papers for the Spring 2018 issue that reflect John Steinbeck’s continued relevance for our time. All critical and theoretical approaches are welcome, as are essays focused on women’s and gender studies, rhetorical concerns, ecology and the environment, international appeal, and comparative studies. Poetry submitted for publication should deal with themes or places associated with Steinbeck’s life and work. Submit papers before January 15, 2018 through the journal’s automated online submission and peer review system at the Pennsylvania State University Press.

A Travel Blogger Considers American Self-Identity on a Visit to Salinas, California

The recent visit my wife Elizabeth I made to Salinas, California included a stop at John Steinbeck’s boyhood home. It brought back a flood of memories, and it made me think about self-identity. That felt right in the moment because America’s sense of itself was a major concern of Steinbeck’s writing.

America’s sense of itself was a major concern of John Steinbeck’s writing.

When I was a boy I devoured Steinbeck’s books. By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style. Years later my brother John and I produced travel films and documentaries, and one of the films we made, California: A Tribute, featured a segment on John Steinbeck and the trips to California’s Central Valley that led him to write The Grapes of Wrath. Seeing the Steinbeck House reminded me of the outrage Steinbeck felt about the thousands of dispossessed families from the American Dust Bowl who had made the long trek to California in search of agricultural jobs and a better life, only to find themselves destitute, hungry, and homeless, ready to accept work at any pay so that they could survive and feed their children.

By age 16 I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I spent hours copying passages from Steinbeck to get the hang of his style.

On a broader scale, the visit to the Steinbeck House made me think about the course of our nation’s history, about the millions of dispossessed foreigners who came to our shores and borders, fleeing persecution and homelessness and poverty, in search of a better life for themselves and their families, just like John Steinbeck’s American refugees. Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in The Grapes of Wrath—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children, sometimes entire families who have already established themselves in our country. Once upon a time we opened our doors to immigrants. Now we’re closing them.

Today we seem to be returning to the posture of the authorities in “The Grapes of Wrath”—denying rights, making arrests, and deporting men, women, and children.

Certainly rules need to be established and followed with respect to immigration. But what is happening now goes beyond rules or regulations. Too many of us are attempting to retreat into a narrow self-identity, building walls against the tide of diversity that has been our distinguishing characteristic as a culture. Who are we as a nation and a people? The comfortable categories of the past are being challenged and shattered in other countries, too, and we feel the same threat to our self-identity that they do. Like John Steinbeck, however, I am optimistic that a new inclusiveness will emerge in the end—the sense of connection and commonality that Steinbeck’s characters achieve in the closing pages of The Grapes of Wrath. The world of the truly human family.

How John Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle Helps Us Navigate Social Discord

Rarely since the Great Depression has our country been as polarized and angry as it is today. On television, in newspapers, on social media, around the office water cooler, in line at the supermarket, even at the family dinner table, there is constant clashing and creating of divisions. Warring political parties, “special interest” groups competing for social change, and an endless series of labels–liberal and conservative, Republican and Democrat, libertarian or evangelical–work to separate us from one another. More and more, Americans are being asked to take sides in this battle of interests and ideas, magnified by social media and the 24-hour news cycle. Inserting sanity into the crock pot of conflicting ideologies can be challenging. Reading John Steinbeck, one of America’s greatest writers and keenest observers, offers a way out of the insanity.

Rarely since the Great Depression has our country been as polarized and angry as it is today.

Eighty years before it was made into a mixed-review movie by the mercurial actor-director James Franco, Steinbeck’s Great Depression labor novel In Dubious Battle explored the complex relationship between the individual and the group, sometimes referred to in Steinbeck’s writing by its more malevolent moniker, “the mob.” Using a strike-torn California apple orchard as his backdrop, Steinbeck deep-dives into phalanx or “group-man” theory, grittily exposing the causes and consequences of a volatile, violent labor struggle involving pickers and organizers, growers and landowners, vigilantes and victims, and outside agitators who are never called “communists” but clearly are.

Steinbeck’s Great Depression labor novel explored the complex relationship between the individual and the group, sometimes referred to in Steinbeck’s writing as ‘the mob.’

In his introduction to the 1995 Penguin Books edition of Steinbeck’s Log from the Sea of Cortez, Richard Astro, Provost Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of English at Drexel University, writes that Steinbeck’s ideas on “group-man” thinking were influenced by the writing of the California biologist William Emerson Ritter (1856-1944). According to Astro, Ritter thought that “in all parts of nature and in nature itself as one gigantic whole, wholes are so related to their parts that not only does the existence of the whole depend upon their orderly co-operation and interdependence of the parts, but the whole exercises a measure of determinative control over its parts.” Ritter also believed that “man is capable of understanding the organismal unity of life and, as a result, can know himself more fully. This, says Ritter, is ‘man’s supreme glory’ – not only ‘that he can know the world, but he can know himself as a knower of the world.’”

Steinbeck’s ideas on ‘group-man’ thinking were influenced by the writing of the California biologist William Emerson Ritter.

Steinbeck illuminates “group-man” thinking in much of his Great Depression fiction, especially the idea that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. But this central tenet of Ritter’s theory is voiced most clearly by the character Doc Burton in the 1936 novel whose title—In Dubious Battle—Steinbeck took from John Milton’s 17th century poem Paradise Lost. Explaining his participation and fascination with the apple pickers’ strike, Burton says, “I want to watch these group-men, for they seem to be a new individual, not at all like single men. A man in a group isn’t himself at all, he’s a cell in an organism that isn’t like him anymore than the cells in your body are like you. I want to watch the group, and see what it’s like. People have said, ‘mobs are crazy, you can’t tell what they’ll do.’ Why don’t people look at mobs as men, but as mobs? A mob nearly always seems to act reasonably, for a mob.”

The central tenet of Ritter’s theory is voiced most clearly by the character Doc Burton in the 1936 novel whose title Steinbeck took from Milton.

As marches, movements, protests, and counter-protests increase in volume and virulence, Steinbeck’s insights into the behavior of “group-man,” through the words and actions of Doc Burton, can be viewed as prescient indeed, particularly by Americans who know their history. Midway through the book, in a passage worthy of one of history’s greatest thinkers–a passage I submit provides an outlook on life that, if adopted, could alleviate much of the rancor in America–Burton says this to the communist agent sent from San Francisco to organize the orchard strike: “That’s why I don’t like to talk very often. Listen to me, Mac. My senses aren’t above reproach, but they’re all I have. I want to see the whole picture–as nearly as I can. I don’t want to put on the blinders of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and limit my vision. If I use the term ‘good’ on a thing I’d lose my license to inspect it, because there might be bad in it. Don’t you see? I want to be able to look at the whole thing.”

Steinbeck’s insights into the behavior of ‘group-man’ can be viewed as prescient, particularly by Americans who know their history.

In “John Steinbeck, American Writer,” Susan Shillinglaw, Professor of English at San Jose State University, notes that “in most of his fiction Steinbeck includes a ‘Doc’ figure, a wise observer of life who epitomizes [Steinbeck’s] idealized stance of the non-teleological thinker.” Non-teleological thinking, she explains, is “‘is’ thinking” marked by “detached observation” and a “remarkable quality for acceptance.” Reinforcing Steinbeck’s obeisance to this philosophy–an open and tolerant approach to ideas and to the people who believe in them that is desperately needed today–Shillinglaw highlights a journal entry made by Steinbeck in 1938: “[T]here is a base theme. Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other. Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love.”

‘[T]here is a base theme. Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other. Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love.’

Eschewing the American impulse to classify, pigeonhole, prejudge, discount, and disparage opposing ideas and those who hold them, Doc Burton prescribes detached observation and personal experience as an alternative to blind theory and blind hatred. Looking back on the unbiased Doc-like worldview favored by his father, Thom Steinbeck told an interviewer in 2012 that Steinbeck always ended his beautifully written letters to his son with this bit of advice: “Good luck. Find out on your own.” Finding out on our own is a good way, perhaps the only way, to survive the dubious battle of ideologies raging within and around us in 2017.

Are British Newspapers Brighter? The Guardian Shines on Tortilla Flat

Word that readers of England’s Guardian newspaper chose Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row as books of the month for April pleased Steinbeck fans in and outside Great Britain. Steinbeck was an on-and-off-again journalist, and England became his temporary home twice—in 1943, when he was an American war correspondent in London, and in 1959, when he and his wife Elaine spent blissful months in a Somerset cottage that dated from Norman times. The Guardian’s current book-of-the-month blog also brings to mind Steinbeck’s critique of American war reporting from London as lazy, unintelligent, and banal. British newspapers vary in quality, but the best are brilliant in a literary way, and it’s hard to imagine an American paper giving Tortilla Flat the sustained, incisive treatment found in the Guardian blog. But American and British newspapers have one thing in common that Steinbeck, who could be cynical, would probably find unsurprising. The bad ones have caught tabloid fever, and the good ones have taken to asking for contributions to help them stay alive. Check out the Guardian newspaper’s blog on Tortilla Flat for evidence of British brilliance—and the lengths to which impecunity is driving intelligent journalism in Great Britain and the United States.

Guardian newspaper photograph of John Steinbeck from Rolls Press/Popperfoto/Getty.

John Steinbeck Saw “Fake News” Coming When Donald Trump Was Still In Diapers

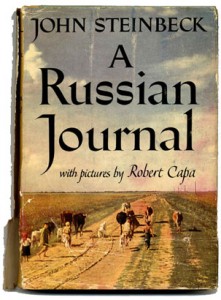

Did John Steinbeck discover “fake news” seven decades before President Donald Trump? Based on what he wrote about the mainstream media of his day in A Russian Journal, the author of The Grapes of Wrath came pretty close.

A Russian Journal is Steinbeck’s first-person journalistic account of the trip he took with photographer Robert Capa in 1947 to the war-battered Soviet Union. In Chapter 1, before he sets off for Russia, Steinbeck describes why he and Capa mistrusted the way the news in America was being gathered, edited, and disseminated by the dominant print and electronic media of their day. It has a familiar ring:

A Russian Journal is Steinbeck’s first-person journalistic account of the trip he took with photographer Robert Capa in 1947 to the war-battered Soviet Union. In Chapter 1, before he sets off for Russia, Steinbeck describes why he and Capa mistrusted the way the news in America was being gathered, edited, and disseminated by the dominant print and electronic media of their day. It has a familiar ring:

We were depressed, not so much by the news but by the handling of it. For news is no longer news, at least that part of it which draws the most attention. News has become a matter of punditry. A man sitting at a desk in Washington or New York reads the cables and rearranges them to fit his own mental pattern and his by-line. What we often read as news now is not news at all but the opinion of one of half a dozen pundits as to what that news means.

Steinbeck didn’t call it “fake news.” And he was complaining about bias in the media from a partisan New York liberal Democrat’s point of view. But anyone whose politics are not located in the dead center of the political spectrum today can feel his pain.

Claims of political bias or slanted news coverage from the left and right were nothing new when A Russian Journal was published in 1948, and they’ve been with us ever since. Conservatives have complained about the liberal East Coast media for half a century. In the babble of our Talk Radio/Cable News/Digital Age the mainstream media is criticized 24/7 from a thousand sane and insane places. No faction is happy with the spin of the news. In 2016 a Bernie supporter or a lifelong Nation magazine subscriber was just as likely to be unhappy with CNN’s coverage of the election as a member of the Tea Party.

The Mainstream Media’s Loss was Literature’s Gain

Though the young John Steinbeck was sacked as a New York City newspaper reporter because he couldn’t stop using his literary skills to improve on the facts, he was basically a journalist. A literary journalist. He had a love-hate for the journalism profession and its practitioners. He envied the ability of reporters to parachute into a strange place and quickly come up with the basic facts for a news story. But he also knew from experience that no journalist or writer—no matter how great—ever gets the whole story or captures more than just a glint of what really happened in a bank robbery, a presidential campaign, or a world war. He wrote this in A Russian Journal:

Capa came back with about four thousand negatives, and I with several hundred pages of notes. We have wondered how to set this trip down and, after much discussion, have decided to write it as it happened, day by day, experience by experience, and sight by sight, without departmentalizing. We shall write what we saw and heard. I know that this is contrary to a large part of modern journalism, but for that very reason it might be a relief. . . . This is just what happened to us. It is not the Russian story, but simply a Russian story.

Steinbeck’s journalism was super-subjective–sometimes to a fault. Russian Journal was his story about the backward, unfree, monstrous USSR he glimpsed in 1947, just as Travels with Charley was his subjective story about the 1960 America he saw on his iconic 10,000-mile road trip. Both books started out as works of nonfiction–as ambitious acts of serious, albeit personal, journalism. In Charley the many fictions Steinbeck slipped into his story about America overwhelmed the “true” facts, and after 50 years its publishers had to admit that it was so fictionalized Charley could not be considered a credible account of how he traveled or whom he really met.

Steinbeck’s journalism was super-subjective–sometimes to a fault. Russian Journal was his story about the backward, unfree, monstrous USSR he glimpsed in 1947, just as Travels with Charley was his subjective story about the 1960 America he saw on his iconic 10,000-mile road trip. Both books started out as works of nonfiction–as ambitious acts of serious, albeit personal, journalism. In Charley the many fictions Steinbeck slipped into his story about America overwhelmed the “true” facts, and after 50 years its publishers had to admit that it was so fictionalized Charley could not be considered a credible account of how he traveled or whom he really met.

A Russian Journal has suffered no such loss of credibility. It’s a great work of subjective journalism—a rare glimpse into a dark and alien world by a keen observer. Anyone teaching college students how to report and write in a precise, interesting, and powerful way would be smart to have them study how well Steinbeck did it—his way, and under trying circumstances .

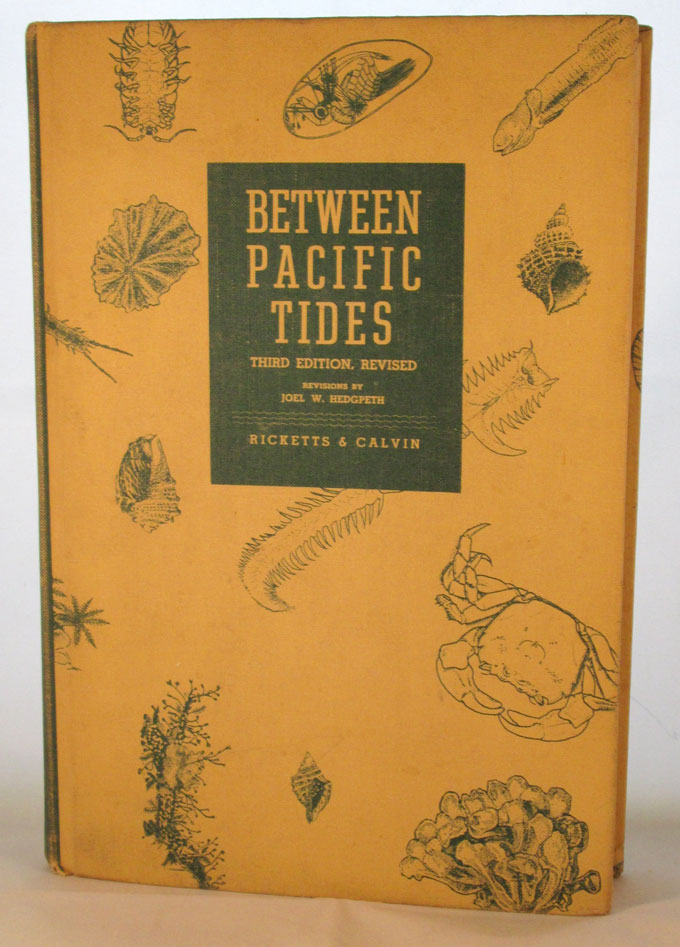

Why Stanford University Delayed Ed Ricketts’s Book

Sea of Cortez, the record of John Steinbeck’s 1940 exploration of Baja California with Edward F. Ricketts, has become a familiar source for fans of both men, and for students of marine biology. Less well known is the story behind Between Pacific Tides, the pioneering marine biology text by Ricketts and Jack Calvin, another Steinbeck friend, published by Stanford University in 1939, the year The Grapes of Wrath appeared. My research on the history of the Hopkins Seaside Laboratory and Hopkins Marine Station, and the Chautauqua nature study movement in Pacific Grove, touches on a formative phase in the life of Steinbeck, who took a summer biology course while a Stanford University student that helped set the stage for his introduction to Ricketts when Steinbeck, who left college in 1925, moved to Pacific Grove.

My research addresses intriguing questions about Ed Ricketts and his book raised by biographers, critics, and historians. The proposal for Between Pacific Tides was presented to Stanford University Press in 1930, the year Ricketts and Steinbeck met. Was the book’s publication slowed by the Director of Hopkins Marine Station Walter K. Fisher’s critical review of the manuscript? Did Stanford University Press dislike the ecological approach taken by Ricketts, whose holistic science and philosophy profoundly influenced Steinbeck’s thought and writing? Was Ricketts completely isolated from the scientific community of Hopkins Marine Station, as has often been suggested? The discovery of numerous letters between Ricketts, Stanford University Press, and invertebrate specialists around the world provides answers to these and other questions, chapter by chapter, in the book that I am writing about the delayed publication of Between Pacific Tides.

My research addresses intriguing questions about Ed Ricketts and his book raised by biographers, critics, and historians. The proposal for Between Pacific Tides was presented to Stanford University Press in 1930, the year Ricketts and Steinbeck met. Was the book’s publication slowed by the Director of Hopkins Marine Station Walter K. Fisher’s critical review of the manuscript? Did Stanford University Press dislike the ecological approach taken by Ricketts, whose holistic science and philosophy profoundly influenced Steinbeck’s thought and writing? Was Ricketts completely isolated from the scientific community of Hopkins Marine Station, as has often been suggested? The discovery of numerous letters between Ricketts, Stanford University Press, and invertebrate specialists around the world provides answers to these and other questions, chapter by chapter, in the book that I am writing about the delayed publication of Between Pacific Tides.

Rousing Post Recalls Cold War, Citing John Steinbeck

“Revisiting John Steinbeck’s A Russian Journal from 1948”—an impassioned website post dated March 21, 2017—reminds readers that John Steinbeck and Robert Capa overcame opposition from left and right in reporting firsthand on daily life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin following World War II. A publication of the International Committee of the Fourth International, the World Socialist site revives Cold War rhetoric in attacking the forces of fascism, Stalinism, and reactionary capitalism that combined to make the lives of ordinary Russians as miserable as possible before, during, and after the war. The language of the post sounds outdated, but the author’s idea accords with the view of John Steinbeck, whom she credits for accuracy and bravery in the face of threats at home and in Russia. “While the Soviet Union was destroyed more than 25 years ago by the Stalinist bureaucracy,” she writes, “the experiences of the Second World War continue to shape the consciousness of millions in the former USSR. Despite certain limitations, this work by Steinbeck and Capa provides valuable insight into the historical experiences of the working class and peasantry of the former USSR.” Timely praise.

“Revisiting John Steinbeck’s A Russian Journal from 1948”—an impassioned website post dated March 21, 2017—reminds readers that John Steinbeck and Robert Capa overcame opposition from left and right in reporting firsthand on daily life in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin following World War II. A publication of the International Committee of the Fourth International, the World Socialist site revives Cold War rhetoric in attacking the forces of fascism, Stalinism, and reactionary capitalism that combined to make the lives of ordinary Russians as miserable as possible before, during, and after the war. The language of the post sounds outdated, but the author’s idea accords with the view of John Steinbeck, whom she credits for accuracy and bravery in the face of threats at home and in Russia. “While the Soviet Union was destroyed more than 25 years ago by the Stalinist bureaucracy,” she writes, “the experiences of the Second World War continue to shape the consciousness of millions in the former USSR. Despite certain limitations, this work by Steinbeck and Capa provides valuable insight into the historical experiences of the working class and peasantry of the former USSR.” Timely praise.

Cracker Barrel Wisdom on John Steinbeck’s Birthday

Craig Nagel, author of the biweekly “Cracker Barrel” column in the Echo Journal, a community newspaper near Brainerd, Minnesota, celebrated John Steinbeck’s birthday with a memorable March 3 column written (as Nagel says of Steinbeck) “so simply and cleanly that his sentences seem effortless.” A Midwestern mensch in the style of Garrison Keillor, Nagel praises Steinbeck for displaying personal bravery in the face of public criticism, and for having a Twain-like sense of humor that “often masked the depth of his outrage, gentling the hatred he felt toward those who used and manipulated others.” Pequot Lakes, the Minnesota town where Nagel lives and writes his “Cracker Barrel” column, has a population of 2,200—about the size of Salinas, California when Steinbeck was born there 115 years ago. Like Salinas, it’s a small place harboring a big heart.

John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Stephen King’s Alternate History of America

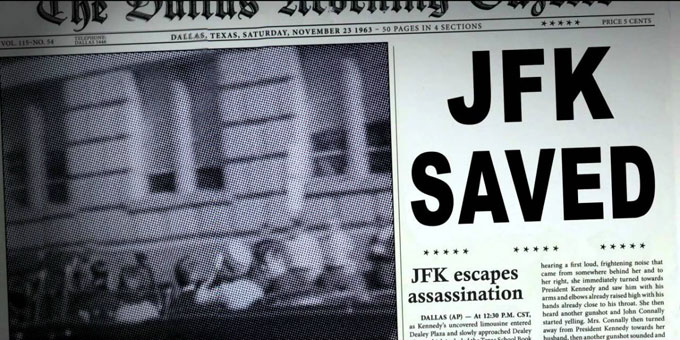

John Steinbeck wasn’t a fan of science fiction, but Stephen King, the reigning master of the form, is a fan of Steinbeck and his books, including Of Mice and Men. Steinbeck’s 1937 novella about George and Lennie plays a particularly important role in 11/22/63, King’s alternate history of America, published on November 8, 2011, five years to the day before Americans elect their 45th president. The TV adaptation of King’s novel downplayed Of Mice and Men but mentioned Steinbeck and starred James Franco, who played George on Broadway and Mac in the 2016 movie adaptation of In Dubious Battle. Like Steinbeck’s 1936 novel about the conflict between modern labor and capital, King’s horror-history of America after 1963 is powerful projection of a political divide that Steinbeck regretted but understood.

Of Mice and Men aside, the major alteration made in Hulu TV’s version of 11/22/63 is in the chain of events set in motion by Franco’s character, a high school English teacher from Maine who time-travels to Dallas to stop Lee Harvey Oswald from assassinating John Kennedy. While underscoring the danger of messing with the past, which like Texas resists interference, King’s story also deals with complexities of cause, effect, and unintended consequences around issues that preoccupy Americans from both political camps today—terrorism, race relations, and climate change, whether acknowledged (Hillary Clinton) or denied (Donald Trump).

In King’s alternate history of America, Kennedy lives to serve two terms but fails to enact civil rights legislation, end the escalating war in Southeast Asia, or prevent the election of George Wallace in 1968. President Wallace—a proto-Trump figure with a trigger-happy VP—firebombs Chicago, goes nuclear in Vietnam, and leaves an apocalyptic mess for a series of feckless, one-term successors that includes Humphrey, Reagan, and Clinton (Hillary, not Bill). Skipping this intervening narrative, the Hulu miniseries fast-forwards to a post-apocalyptic America populated by alien “Kennedy camps” and terrorist street gangs with dirty bombs—a version of alternate history certain to offend people who revere Kennedy while fulfilling the worst fears of those who revile Donald Trump.

Both groups include fans who will be disappointed in the diminished attention paid to John Steinbeck in the TV version of 11/22/63, where Of Mice and Men is basically limited to a favorite-book comment made by Franco’s character to the librarian who becomes his love interest. In the novel, long but not too long at 850 pages, Of Mice and Men provides dramatic depth, character development, and thematic amplification absent from the eight-part miniseries. Early in the book Franco’s character ponders the challenge of “exposing sixteen-year-olds to the wonders of Shakespeare, Steinbeck, and Shirley Jackson.” Later, while teaching in Texas, he directs Of Mice and Men in a high school production that provides a dimension of joy sadly missing from the miniseries: “At that moment I cared more about Of Mice and Men than I did about Lee Harvey Oswald . . . . I thought that Vince looked like Henry Fonda In The Grapes of Wrath.”

Of Mice and Men Helps 11/22/63 Connect with America

Stephen King, who co-wrote and produced the Hulu series, must share the blame—if that’s the word—for shortchanging John Steinbeck in the interest of narrative compression. The loss is regrettable, and in light of another change unnecessary as well. The first incidence of time travel in the novel takes place in the fictional town of Derry, Maine, a nightmare venue familiar to Stephen King fans from his other books. This episode is important, and it includes a character named Bill Turcotte, a slow-moving, middle-aged loser who threatens Franco’s character and gets left behind in Derry. In the TV version, the Derry action takes place in Kentucky and Turcotte—a wound-up ingénue—stays in the story as a sidekick, all the way to Dallas and the confrontation with Oswald. Unlike Derry and its scary clowns, Turcotte’s Kentucky feels tame. And the time devoted to his character, played by a 23-year-old English actor with a lousy Southern accent, would have been better invested in keeping Of Mice and Men, an essential piece of Americana, in the picture.

Stephen King, who co-wrote and produced the Hulu series, must share the blame—if that’s the word—for shortchanging John Steinbeck in the interest of narrative compression. The loss is regrettable, and in light of another change unnecessary as well. The first incidence of time travel in the novel takes place in the fictional town of Derry, Maine, a nightmare venue familiar to Stephen King fans from his other books. This episode is important, and it includes a character named Bill Turcotte, a slow-moving, middle-aged loser who threatens Franco’s character and gets left behind in Derry. In the TV version, the Derry action takes place in Kentucky and Turcotte—a wound-up ingénue—stays in the story as a sidekick, all the way to Dallas and the confrontation with Oswald. Unlike Derry and its scary clowns, Turcotte’s Kentucky feels tame. And the time devoted to his character, played by a 23-year-old English actor with a lousy Southern accent, would have been better invested in keeping Of Mice and Men, an essential piece of Americana, in the picture.

John Steinbeck, Donald Trump, and the King of Horror

But that’s a quibble. More important is the attention drawn to the phenomenon described years ago by the historian Richard Hofstadter as the paranoid style in American politics. During a recent interview with the book editor of The Washington Post, Stephen King confessed that “a Trump presidency scares me more than anything else.” Exercising and exorcising paranoia is what King does in his writing, of course, so whatever the outcome of this week’s election, it’s safe to assume that a scary-Trump novel will be making us scream soon. Maybe an alternate history of America since 2011? With John Steinbeck as a modern-day time traveler on a mission, like James Franco’s character in 11/22/63, to rewrite the record and save us from ourselves?

But that’s a quibble. More important is the attention drawn to the phenomenon described years ago by the historian Richard Hofstadter as the paranoid style in American politics. During a recent interview with the book editor of The Washington Post, Stephen King confessed that “a Trump presidency scares me more than anything else.” Exercising and exorcising paranoia is what King does in his writing, of course, so whatever the outcome of this week’s election, it’s safe to assume that a scary-Trump novel will be making us scream soon. Maybe an alternate history of America since 2011? With John Steinbeck as a modern-day time traveler on a mission, like James Franco’s character in 11/22/63, to rewrite the record and save us from ourselves?