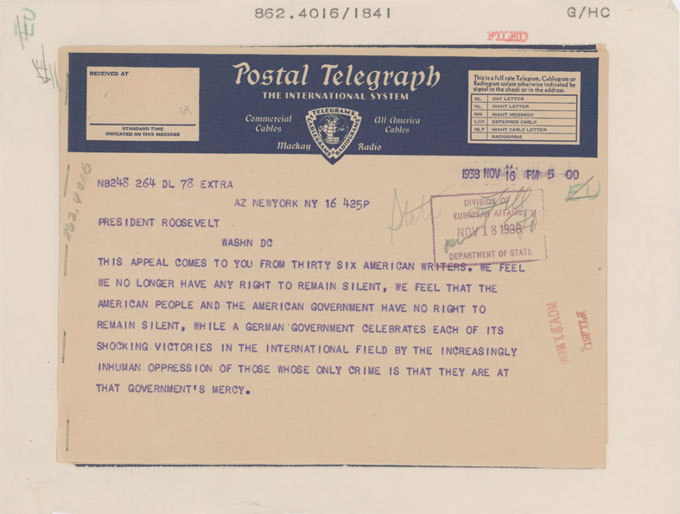

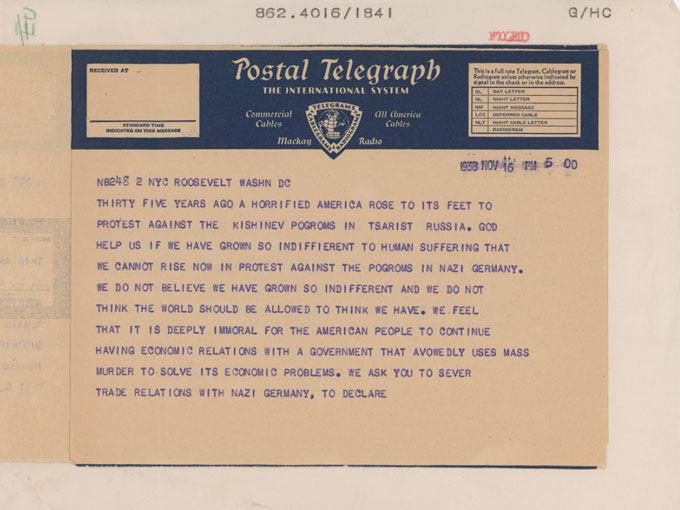

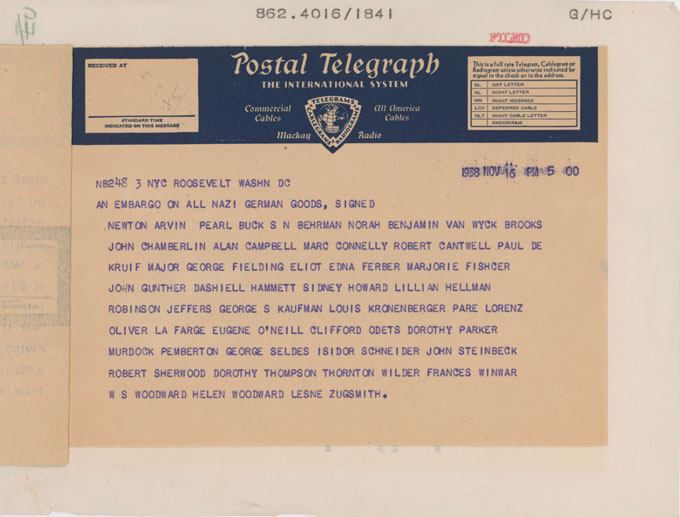

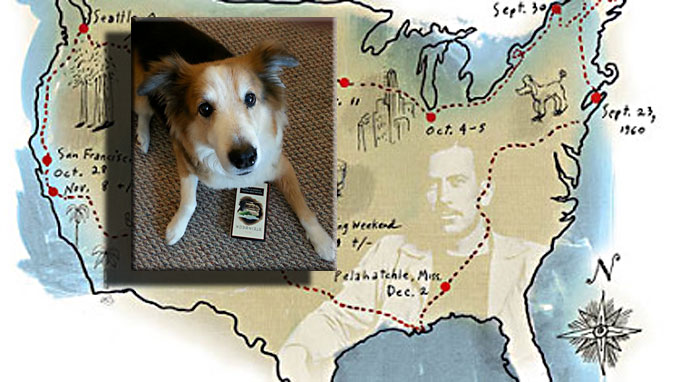

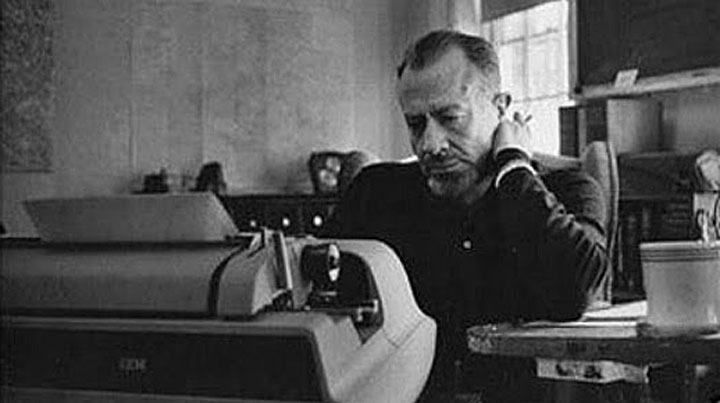

On November 16, 1938—three years before America formally entered the war against Germany—John Steinbeck joined 35 writers in urging Franklin Roosevelt to confront the Third Reich. Responding to the outrage known as Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, their telegram (shown here) recommended severing economic ties with Hitler’s regime, the equivalent of today’s sanctions against Iran. Signed by Steinbeck, George S. Kaufman, Pare Lorentz, Robinson Jeffers, and other writers known by Steinbeck, the message was one of many received by Franklin Roosevelt urging action against the Nazi regime. But this one meant more than most. The signers were all working artists at the whim of a domestic audience that, as today, was deeply divided, and powerful voices—including Charles Lindbergh, Joseph Kennedy, and the right-wing radio priest Charles Coughlin—opposed U.S. intervention on behalf of European Jews for economic, political, and racist reasons. As John Bell Smithback notes in his time-machine fantasy about the rise of the Third Reich and the telegram sent to Franklin Roosevelt, John Steinbeck and other progressives were correct in their assessment: Kristallnach was a dress rehearsal for the Holocaust. When he signed his name, Steinbeck had yet to meet Franklin Roosevelt, but his work was already controversial, so his action took courage. John Bell Smithback’s imaginative account of the Kristallnach atrocity and Steinbeck’s public response is a timely reminder that Steinbeck’s instinctive sympathy for victims was profound and prophetic—and that 1938 was like 2015 in deeply disturbing ways. The Third Reich was new, The Grapes of Wrath was in manuscript, and John Steinbeck was in his thirties when the terrifying events of 1933 and 1938 transpired.—Ed.

Catching Up with Steinbeck in My Time Machine

The UPS deliver man has just dropped off one of those spiffy new portable time machines that everyone is talking about. I’ve nearly finished setting it up, but I’m not going to use it to take a trip into the future. Everyone seems to be doing that, but observing what a stinking mess the world’s in I’m going to have a look into the past to see if there are any comparisons to be made. Accordingly, I’ve set the dial for the year 1933, and lo . . . here I am in Berlin! The Reichstag building has gone up in flames and the Nazis are claiming it’s the work of foreign terrorists. Consequently, they’ve issued a Decree for the Protection of People and State that gives them sweeping new powers to deal with a so-called emergency. Déjà vu: didn’t we go through this kind of thing when a few men burned down our Twin Towers?

Déjà vu: didn’t we go through this kind of thing when a few men burned down our Twin Towers?

Fine-tuning my time machine, I see thousands of people being arrested and sent to a camp where guards are being taught terror tactics to dehumanize prisoners. I thought it might be Abu Ghraib or maybe Guantanamo, but no, this place is called Dachau. Back in Berlin, though the democratically elected president of the country is a man named Paul von Hindenburg, the Nazis have gone around him to pass the Enabling Act allowing Hitler to issue laws without the Reichstag’s approval. Déjà vu again as I’m reminded of the House and Senate going around our president to manipulate U.S. foreign policy by inviting foreign politicians to speak in Washington and by addressing threatening, perhaps treasonous letters to foreign governments warning them not to declare peace.

Déjà vu again as I’m reminded of the House and Senate going around our president to manipulate U.S. foreign policy by inviting foreign politicians to speak in Washington and by addressing threatening, perhaps treasonous letters to foreign governments warning them not to declare peace.

I take a moment to catch my breath, and as I inhale I detect the scent of burning books and see 40,000 people in the square at the State Opera to hear Joseph Goebbels deliver a fiery address: “No to decadence and moral corruption! Yes to decency and morality in family and state! I consign to the flames the writings of . . . .” Hitler’s Karl Rove stands on a platform gripping a microphone, his voice rising ever higher as he screams the names of writers banned by the Third Reich: “Heinrich Mann, Walter Benjamin, Bertholt Brecht, Max Brod, Heinrich Heine, Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque . . . .”

Hitler’s Karl Rove stands on a platform gripping a microphone, his voice rising ever higher as he screams the names of writers banned by the Third Reich.

Sigmund Freud is on the list; so are Gorki, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Victor Hugo, Andre Gidé, Karl Marx, Emile Zola, and Marcel Proust—”Und auch die amerikanische Schriftstellern, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, Jack London, John Dos Passos, John Steinbeck . . . .” A pillar of smoke rises over the square and sparks from books by hundreds of internationally acclaimed authors and poets, philosophers and rationalists, drift skyward. Ashes falling on my shoulders to remind me of Senator Joseph McCarthy, of the House Un-American Activities Committee, and of the American Library Association asserting that each year it receives hundreds of challenges to remove dangerous works from the shelves of American libraries. At the top of the current list are books about the imaginary childhood of a British boy named Harry Potter.

Sigmund Freud is on the list; so are Gorki, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Victor Hugo, Andre Gidé, Karl Marx, Emile Zola, Marcel Proust, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, Jack London, John Dos Passos, and John Steinbeck.

It is late, but the crowd seems reluctant to disperse. PR people put away their motion picture cameras and groups of tough-looking men and boys in brown-shirted uniforms slink off to beer cellars. Newsmen rush to their offices, and then there is a hush. I press a button and inch my time machine forward, eager to see how the events of the evening are received overseas. Thinking that a pyre this big would sound warning bells around the world, I anticipate outrage. But what is this? Except for the living writers who learned that their books had just gone up in smoke, there are few outside Germany expressing concern about what’s happened. Within Germany, it seems to be a case of “Who needs books when we have Joseph Goebbels?” I pause to ponder this failure of reason. Is it really so different today? “Who needs factual information when we have Roger Ailes?”

Except for the living writers who learned that their books had just gone up in smoke, there are few outside Germany expressing concern about what’s happened.

At this point everything becomes a blur of red, white and black, of symbols and banners and uniforms and parades. Martial music blasts from lampposts, and at dawn I stop at a boulevard café to have a look at the newspapers. The only one at hand is Völkischer Beobachter, Hitler’s paper. He owns the whole thing, lock, stock and barrel, much, I suppose, as Rupert Murdoch owns and controls media throughout the English-speaking world today. There are fear stories on every page, and if it’s not one crazy group accused of threatening the nation it’s another; raving anarchists, murderous communists, and stealthy homosexuals are around every corner. Judging from what I read, there are unseen forces everywhere conspiring to rip out the German soul. That’s the reason given for the new Law for Removing the Distress of the People and the Reich. In an instant, German Jews are stripped of their civil rights, and I note that the man behind the decree, the one who will provide the balm, is none other than the Leader himself.

In an instant, German Jews are stripped of their civil rights, and I note that the man behind the decree, the one who will provide the balm, is none other than the Leader himself.

A group of youths march by the café in wrinkled uniforms. I turn to the editorial page and am astonished. Beneath the screaming headline—“We Need A Fascist Government In This Country”—I read this: “We need a fascist government in this country to save the nation from the communists who want to tear it down and wreck all that we have built. The only men who have the patriotism to do it are the soldiers, and Smedley Butler is the ideal leader. He could organize a million men overnight.”

Smedley Butler? What in the hell is this? He’s not even German: he’s an American general in command of an army of 500,000 war veterans back in the United States.

The Nazi editorial explains the American connection: “We have got the newspapers. We will start a campaign that President Franklin Roosevelt’s health is failing. Everyone can tell that by looking at him, and the dumb American people will fall for it in a second . . . .” So says Gerald MacGuire, a Wall Street bond salesman and one of the financiers of a group known as the American Liberty League, a corporate cabal that includes the heads of General Electric, Goodyear Tire, Bethlehem Steel, DuPont, J.P. Morgan, and Ford. Praising the prescience of these America First! patriots, the Völkischer Beobachter refers with approval to the racist ravings of Father Coughlin, the popular radio commentator from Henry Ford’s hometown. It seems Germany had highly placed friends in the United States. Why am I so shocked, I ask, as I think of today’s EIB Network and Fox News, of Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Lars Larson, Bill O’Reilly, and the America First! Tea Party?

It seems Germany had highly placed friends in the United States. Why am I so shocked, I ask, as I think of today’s EIB Network and Fox News, of Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity, Lars Larson, Bill O’Reilly, and the America First! Tea Party?

On the streets of Berlin people have lifted their arms in the Sieg heil salute, and I hear voices, thousands upon thousands, singing: “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles!“ I watch transfixed as German troops march into Vienna, and I hear the world’s silence. Three months later I see Nazi soldiers marching into Prague . . . and hear the world’s silence. Then, on the night of November 10, this message is posted from SS-Grupenführer Reihnard Heydrich to all German State Police Main Offices and Field Offices:

DATE: 10 November 1938

RE: Measures Against Jews Tonight

(a) Only such measures may be taken which do not jeopardize German life or property (for instance, burning of synagogues only if there is no danger of fires for the neighborhoods).

(b) Business establishments and homes of Jews may be destroyed but not looted. The police have been instructed to supervise the execution of these directives and to arrest looters.

(c) In business streets special care is to be taken that non-Jewish establishments will be safeguarded at all cost against damage.

As soon as the events of this night permit the use of the designated officers, as many Jews (particularly wealthy ones) as the local jails will hold are to be arrested in all districts—initially only healthy male Jews, not too old. After the arrests have been carried out the appropriate concentration camp is to be contacted immediately with a view to a quick transfer of the Jews to the camps.

What follows is a night of absolute destruction, later labeled Kristallnacht, the Night of Smashed Glass. Hitler Youth and the brown-shirted S.A. have destroyed 167 synagogues and shattered the windows of an estimated 7,500 Jewish-owned shops and businesses. Throughout all of Germany, Austria, and Nazi-occupied Sudetenland, mobs are roaming the streets attacking Jewish residents in their homes. Although murder did not figure in the official directive, Kristallnacht will claim the lives of at least 91 Jews. Police records of the period document a high number of rapes and of suicides in the aftermath of the violence: a fine of one billion marks is to be levied, not upon the criminals, but upon the victims.

Although murder did not figure in the official directive, Kristallnacht will claim the lives of at least 91 Jews. Police records of the period document a high number of rapes and of suicides in the aftermath of the violence: a fine of one billion marks is to be levied, not upon the criminals, but upon the victims.

Outraged, a group of writers in the United States, John Steinbeck among them, sends a telegram to President Franklin Roosevelt asking him to sever economic ties with Nazi Germany. Unfortunately for history, no action will be taken by the administration in time to help the Jews. But I don’t need a time machine to tell me that.