In The Grapes of Wrath John Steinbeck explores social ecology—how individuals interact with each other within their natural, adopted, and built environments—in the crisis created by the Great Depression Dust Bowl. Social ecology recognizes the holistic connection of all elements and influences and how each affects the other in a social complex. Reading The Moon Is Down, Cannery Row, and The Grapes of Wrath helped me discover how the principles of social ecology can be applied in practice.

In The Grapes of Wrath John Steinbeck explores social ecology—how individuals interact with each other within their natural, adopted, and built environments—in the crisis created by the Great Depression Dust Bowl. Social ecology recognizes the holistic connection of all elements and influences and how each affects the other in a social complex. Reading The Moon Is Down, Cannery Row, and The Grapes of Wrath helped me discover how the principles of social ecology can be applied in practice.

Steinbeck’s depiction of the Dust Bowl and its impact in The Grapes of Wrath clearly demonstrates his familiarity with the ecological disaster resulting from the failure to shift to dry land farming methods before drought conditions overtook large areas of America’s heartland in the 1930s. What is less apparent is the other side of the story, the social ecology disaster that occurred when Dust Bowl migrants tried to find paying work and a new home in California. In The Grapes of Wrath the author adroitly brings together both kinds of environment, social and physical.

The Phalanx in The Moon Is Down and on Cannery Row

My first exposure to John Steinbeck’s understanding of social ecology occurred when I read The Moon Is Down, the play-novelette he wrote for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in 1942. This work—which Steinbeck is believed to have based on the Nazi occupation of Norway—exerted significant influence on the development of my thinking about social ecology. Steinbeck’s story concerns the resistance by the residents of an unnamed coastal village in northern Europe to foreign-army occupiers who invade the town in order to seize its harbor and coal mine.

Their resistance through non-compliance rests on the concept of the informal network, an element of the broader idea behind Steinbeck’s phalanx theory. The phalanx encompasses the entire environment and includes driving forces, unconscious influences, and factors that are physical, social, and cultural; informal networks are the means by which information is disseminated, issues are resolved, and environments are managed in a particular community without using formal systems.

The phalanx encompasses the entire environment and includes driving forces, unconscious influences, and factors that are physical, social, and cultural.

A later example of the function of an informal network within a specific group occurs in Steinbeck’s Cannery Row reprise Sweet Thursday, where Doc’s Western Biological Laboratories, Lee Chong’s Heavenly Flower Grocery, and Ida’s Bear Flag bordello are “bound by gossamer threads of steel to all the others—hurt one, and you aroused vengeance in all. Let sadness come to one, and all wept.” Here Steinbeck’s dramatization of human interconnectedness represents much more than the dynamics between these network nodes or the individuals who comprise them. Rather, it depicts a powerful unconscious influence on the life of the community that functions as its own entity—the phalanx.

(Interestingly, the writer Malcolm Gladwell alludes to the same concept in his 2008 book about super-achievers titled Outliers: The Story of Success. In his introductory chapter Gladwell discusses the people of Roseto, Pennsylvania, a community settled in the late 19th century by immigrants from the town of Roseto Valfortore in Italy. Noting a study 50 years earlier of the low incidence of illness in Roseto—where residents had fewer heart problems than those in towns nearby, no suicides, no alcoholism or drug addiction, little crime, and no one on welfare—Gladwell notes that ”these people were dying of old age, that is it.” When Dr. Stewart Wolfe, the author of this research, studied the health of the people of Roseto, he concluded that the “secret of Roseto was not diet or exercise or genes or location. It was Roseto itself.”)

How Owning The Moon Is Down Became a Capital Crime

In The Moon Is Down John Steinbeck describes his fictional town’s informal network system, the characters in that system and the roles they play, and the bewilderment and frustration of the invaders with the villagers, who don’t behave as expected. The following passage reflects the dramatic difference between a top-down authoritarian type in a position of power, Colonel Lanser, and the informal horizontal system represented by Mayor Orden, a community that is supposedly powerless:

Lanser: “Please co-operate with us for the good of all.” When Mayor Orden made no reply, “For the good of all,” Lanser repeated. “Will you?”

Orden: “This is a little town. I don’t know. The people are confused and so am I.”

Lanser: “But will you try to co-operate?”

Orden shook his head. “I don’t know. When the town makes up its mind what it wants to do, I’ll probably do that.”

Lanser: “But you are the authority.”

Orden smiled. “You won’t believe this, but it is true: authority is in the town. I don’t know how or why, but it is so. This means we cannot act as quickly as you can, but when a direction is set, we all act together. I am confused. I don’t know yet.”

Lanser said wearily, “I hope we can get along together. It will be so much easier for everyone. I hope we can trust you. I don’t like to think of the means the military will take to keep order.”

Orden was silent.

“I hope we can trust you,” Lanser repeated.

Orden put his finger in his ear and wiggled his hand. “I don’t know,” he said.

Steinbeck’s statement about the “authority being in the town” is profound. To Lanser’s amazement, power resides not in a person but in the phalanx. Without analyzing its nature or origin, Orden articulates the insight that something beyond himself exists in the community that would make the silent decision to resist rather than capitulate. Steinbeck’s fictional representation of the power of the phalanx had political consequences. European translations of The Moon Is Down ultimately became operational handbooks for French, Italian, Norwegian, and other resistance movements during World War II. The Germans understood the book’s power. Possessing a copy was punishable by death.

“Threads of Steel” in Cannery Row and Grapes of Wrath

The use of such informal networks—“the gossamer threads of steel”—as a means of empowerment and survival occurs in other works by Steinbeck as well. As noted, Mack and the Boys in Cannery Row provide a good example. So do Danny and his paisanos in Tortilla Flat. In The Grapes of Wrath the power of informal networks is described by Tom Joad’s speech about injustice in the work camps and the need to build a movement—a phalanx—that is as invisible to the formal powers that control the field workers as that of the occupied villagers in The Moon Is Down. Tom expresses this promise to his mother:

“Then it don’ matter. Then I’ll be all aroun’ in the dark. I’ll be ever’where – wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. If Casy knowed, why, I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an’ – I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build – why, I’ll be there.”

Here Steinbeck defines what we now call a community organizer, a person using informal networks to mobilize people in the worlds of social welfare, social justice, political empowerment, and institutional change. But Tom is also referring to a power beyond himself. Even when he could no longer “be around,” his influence would continue in the power of the phalanx of which he had become a part.

Migrant Camp and Cannery Row “Gathering Places”

As far as I am concerned, John Steinbeck was our first social ecologist. In addition to understanding the power of informal networks, the writer realized that an informal network needs somewhere to call home—and that home is found in “gathering places” like Danny’s house in Tortilla Flat and Doc’s lab in Cannery Row, where Mack and the Boys drop in and out at will, reinforcing the importance of having a place where everyone is equal, humor presides, information changes hands, and issues are discussed and resolved in a safe setting. Steinbeck’s relationship with the real-life marine biologist Ed Ricketts, with whom the writer learned to view the world through the lens of ecology, provided the inspiration for Mack and the vocabulary for the writer to translate the principles of marine ecology into the framework of social ecology—but that is a story for another time.

For now it is important to remember that in writing The Grapes of Wrath Steinbeck knew he had to learn through observation and experience about the challenges faced by Dust Bowl migrants, how they dealt with these issues, and how they related to the new environment in which found themselves. In other words, Steinbeck needed a “discovery process”—yet another aspect of social ecology.

In addition to understanding the power of informal networks, the writer realized that an informal network needs somewhere to call home.

The writer’s mentor and guide in this process was Tom Collins, the administrator of Weedpatch, the model migrant camp built by the Farm Security Administration to which Steinbeck gained access. Here and in other outposts where migrants clustered, Steinbeck was seeking more than setting and background for his story; he became intimately involved in understanding the social organization of the people he was writing about. In the process he discovered their survival mechanisms: how they communicated, took care of one other, and managed conflicts internally, even as they appeared powerless to the outside world—like the townspeople in The Moon Is Down.

Steinbeck transforms this knowledge into a fictional migrant labor camp managed by the non-fictional Federal Resettlement Administration. This imaginary camp provides readers of The Grapes of Wrath with an opportunity to observe the migrants’ progression from the social-ecological chaos perpetrated by the Associated Farmers to the creation of social harmony, however fleeting, for families like the Joads. The camp becomes a haven where the Joads and their fellow migrants can predict, participate in, and control their environment in a way that offers stability and protection, however temporary.

Visiting Cannery Row and Applying Social Ecology

In classic “us-versus-them” tradition, Steinbeck uses the camp boundary as a way to illustrate the concept of internal control versus external threat. Inside the camp the migrants are empowered to make decisions about how it is operated. As demonstrated when outside goons try to create a disturbance at a dance, the camp’s residents understand the importance of maintaining and protecting the camp’s boundary. Outside the perimeter they are threatened, exploited, and without power. Inside they exercise control. Preventing or absorbing boundary intrusion is essential to maintaining predictability and control of one’s environment.

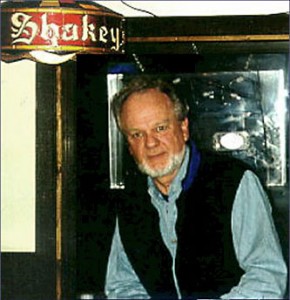

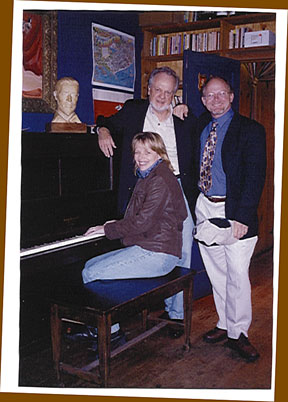

As with The Moon Is Down, reading The Grapes of Wrath nudged me down the path of social ecology, leading me to discover the role of “gathering places” and the importance of creating human geographic boundaries. Both concepts reflect the human need to feel secure; the recognition of how boundaries function, where they are placed, and what they mean in everyday life has become a key element of my writing about social ecology and my work as a consultant. The connection has also occasioned several visits to the current Cannery Row. (On one trip, shown here, I was photographed standing between Joan Resnick and Kevin Preister, director of the Center for Ecology and Public Policy.)

As with The Moon Is Down, reading The Grapes of Wrath nudged me down the path of social ecology, leading me to discover the role of “gathering places” and the importance of creating human geographic boundaries. Both concepts reflect the human need to feel secure; the recognition of how boundaries function, where they are placed, and what they mean in everyday life has become a key element of my writing about social ecology and my work as a consultant. The connection has also occasioned several visits to the current Cannery Row. (On one trip, shown here, I was photographed standing between Joan Resnick and Kevin Preister, director of the Center for Ecology and Public Policy.)

As noted, Steinbeck used the concepts of phalanx, “gathering place,” and boundaries—physical, social, and psychological—in books from Tortilla Flat to Sweet Thursday, a space of 20 years. In each he examines and employs the most basic elements of the human condition to make great stories from which I built the framework of a social ecology theory of my own: the human desire to gather together, to communicate, to feel safe, to care for one another, and to be empowered by using one’s environment creatively. This alone is sufficient cause for me to celebrate the 75th anniversary of The Grapes of Wrath.