Steinbeck: The Untold Stories, a book of short stories by Steve Hauk based on the life of John Steinbeck, will be published by SteinbeckNow.com on July 22. The first print project undertaken by the website, it is the product of a two-year collaboration between Hauk—a playwright in Pacific Grove, California—and Caroline Kline, a Monterey artist with a flair for illustration and a feel for John Steinbeck, whose affinity for art and artists began when he was growing up in the Salinas Valley and eventually extended to Europe. Earlier versions of four of the short stories have appeared online at SteinbeckNow.com. All sixteen feature original art work by Kline inspired by Hauk’s fictional rendering of dramatic episodes—some real, others imagined—from Steinbeck’s storied life in Salinas, Pacific Grove, New York, and beyond.

The House Where Steinbeck Lived and Wrote Needs Help

John Steinbeck was born on February 27, 1902 in the front bedroom of the Victorian house at 132 Central Avenue in Salinas, California. In 1905 he was christened in the parlor of the Queen Anne-style structure—the same room where he later practiced the piano. In the living room he announced that he intended to become a writer. In the basement he regaled neighborhood friends with ghost stories and other tales. In an upstairs bedroom he wrote short stories that he sent to magazines, unsigned, as a teenager. He left for Stanford in 1919; years later he and his wife Carol returned to help care for his dying mother, a former school teacher who insisted that all four of her children go to church, learn piano, and attend college. In the same upstairs bedroom he occupied as a boy he continued to work on The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat, the book that brought him fame when it was published in 1935, the year his father died.

In the upstairs bedroom Steinbeck occupied as a boy he continued to work on The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat, the book that brought him fame when it was published in 1935, the year his father died.

The home was sold following Olive’s death, near the bottom of the Great Depression, in 1934. For the next four decades—years of war, recovery, and modernization—ownership of the aging Victorian house passed through various hands until its purchase by the newly created Valley Guild in 1973. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization created to save the house where Steinbeck was born, the Valley Guild made repairs, conducted research, and produced results that are evident today. The bed in which Steinbeck was born was returned. So were Olive’s desk and table. Steinbeck’s sisters stayed in California, and they and their children and grandchildren made generous gifts of period furnishings and family heirlooms. Thanks to the hard work of Valley Guild volunteers, the Steinbeck House was added to the National Register of Historic Places, a prestigious designation with some practical benefits.

For the next four decades—years of war, recovery, and modernization—ownership of the aging Victorian house passed through various hands until its purchase by the newly created Valley Guild in 1973.

Recognizing the need for an income stream to support ongoing maintenance and preservation, the founders put their heads together and came up with a plan that serves educational and economic goals equally. For five days each week throughout the year the House is open to the public as a lunch restaurant, gift shop, and bookstore operated by a team of 98 dedicated volunteers. The restaurant employs a professional chef and offers a changing menu. Table service is provided by Valley Guild members in period dress—docents in motion who educate diners about Steinbeck while taking orders and serving food. The annual Steinbeck festival and the National Steinbeck Center on Main Street, three blocks from the Steinbeck House, are partners in the enterprise of keeping Salinas, California at the forefront of global interest in Steinbeck’s life and work.

Time Catches Up With Every Victorian—Even Steinbeck’s

Age has its advantages, but keeping a 119-year-old Victorian house in working order is expensive. Not long ago it was discovered that the center of the Steinbeck House, supported by eight posts on brick footings, was slowly sinking. The posts run the length of the basement gift shop and bookstore and serve as the building’s legs. As they go, so goes the body. To prevent collapse, soil engineers and construction experts determined that the deteriorating posts and bases had to be replaced using concrete. Although the restaurant has remained open during the process, the project required closing the gift shop and book store, raising the central beams, and installing temporary supports while making excavations and constructing permanent posts and footings—all necessary to insure the future of John Steinbeck’s birthplace as a public resource.

Using the GoFundMe Page Makes Giving Safe and Easy

The project is well along and, once all expenses are paid, is expected to cost $35,000. The bill, along with the revenue hole caused by the gift store closing, has created an urgent need for funds to keep the Steinbeck House open and operating in the black. The people of Salinas, California are community-minded and do their part. But the Steinbeck House is a national treasure, and help is also needed from friends and fans who live elsewhere. Fortunately this group is growing: visitors from 68 countries and 50 states have enjoyed lunch and a lesson in Steinbeck history while eating at the restaurant. Please do your part to keep the Steinbeck House on its feet. Visit the new GoFundMe page and make your tax-deductible gift to the project. The Victorian house where Steinbeck first wrote fiction is getting on, but just as beautiful as the day Steinbeck was born in the front room of his family home 115 years ago.

The Guardian Tweets Great Britain’s Love for Steinbeck

Book lovers who read The Guardian, the long-lived daily newspaper in Great Britain with an international reach and reputation, picked two distinctively American novels by John Steinbeck—Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row—as this month’s selections for the paper’s reading group. “While Steinbeck himself was a popular choice as an author to help us celebrate the human spirit, winning many nominations for other books,” explained the book editor of The Guardian in a tweet to the group, “this feels like a good result, not least because both novels have their own special kind of glow and warmth.” John and Elaine Steinbeck—avid internationalists who had their pick of pleasant places—spent their happiest year in Great Britain, and literate Brits continue to return the love. “[Steinbeck’s] books still sell in their millions,” The Guardian added. “Here in the UK, Of Mice and Men is a staple of school exams, while The Grapes of Wrath remains a favourite around the world. Almost half a century after Steinbeck’s death, his reputation seems as solid and secure as any writer of his era.” Quite so.

Praise for the Salinas Valley From The New York Times

A travel feature in the February 9 New York Times focused on food and wine in Carmel-by-the-Sea and Salinas, California also paid respects to East of Eden, John Steinbeck’s fictional account of bygone days in the Salinas Valley, where agriculture is still king. If you enjoy eating, drinking, and Steinbeck in that order, What to Find in Salinas Valley: Lush Fields, Good Wine and, Yes, Steinbeck is worth your time, whether your summer travel plans include grazing your way through Steinbeck Country or packing East of Eden with the lemonade and sandwiches for an afternoon getaway closer to home.

Photograph of the Salinas Valley by David Laws.

What The New York Times, The Charlotte Observer, and Christianity Today Had to Say About John Steinbeck

Three recent newspaper stories served as reminders that John Steinbeck remains relevant to readers, and useful to editors, experts, and leaders who make policy in his name. Of Mice and Men dominated the August 22 New York Times report on a Texas death penalty case working its way to the Supreme Court. The Grapes of Wrath appeared in the headline of a report on Syrian refugees published the same day in Christianity Today. The 1939 novel was used by a college professor with conservative ideas about government in an August 20 editorial for The Charlotte Observer. The New York Times and Christianity Today articles reflected Steinbeck’s values. The editorial in The Charlotte Observer showed why he took a dim view of academics.

The New York Times and Christianity Today articles reflected Steinbeck’s values. The editorial in The Charlotte Observer showed why he took a dim view of academics.

The New York Times piece by Adam Liptak explored the legality and ethics of the so-called Lennie standard, named for the character Lennie Small and used to decide when a person of limited intelligence should or shouldn’t be executed for murder. (Barbara A. Heavilin, who writes frequently about John Steinbeck, explains the immorality of this misreading of Steinbeck”s novel in a related blog post.) Jeremy Weber’s Christianity Today report on refugees in the Bekaa Valley—“Grapes of Wrath: Refugees Face Steinbeck Scenario in Lebanon’s Napa Valley”—compared conditions there with California during the Great Depression. In his editorial for The Charlotte Observer—“Addressing the problems of the modern-day Joads“—Professor Clark G. Ross misrepresented Steinbeck’s intentions in The Grapes of Wrath, just as those justifying the death penalty do in misreading Of Mice and Men.

Why The Charlotte Observer Got John Steinbeck Wrong

Professor Ross describes teaching The Grapes of Wrath to a group of students who are studying the Depression for the first time. His detached view of the Joads as a “fundamentally Christian, not over-educated family” dependent on government support for survival suggests that the wrong lesson was learned about the present. While faulting both Republicans and Democrats for failing workers losing their jobs to foreign labor, he claims that politicians can’t save these “modern-day Joads” anyway, because government isn’t the solution to social problems. Steinbeck thought it was and Weedpatch, the federal camp where the Joads get help, was his proof. Unconvinced by Steinbeck’s example, Ross characterizes Steinbeck’s vision as “centered on a benevolent government within a communist society, one that would provide employment and shelter, as well as self-governance.” The commie charge isn’t new.

Steinbeck thought government was the solution to social problems. Weedpatch, the federal camp where the Joads get help in The Grapes of Wrath, was his proof.

Conservative critics raised the specter of communism to discredit Steinbeck and his novel when it was published more than 75 years ago. Critics in California denied that Okies like the Joads even existed, or if they did were as numerous as Steinbeck claimed, and they failed to feel the Joads’ or Steinbeck’s pain. Professor Ross expresses sympathy, but it’s distant and distorted by doctrine. Like that of Joad Deniers at the time, his claim that Steinbeck’s version of good government can’t succeed requires a belief that government can’t be the solution because it’s the problem. “History has proven,” he says of Steinbeck’s dream, “that such public provision of goods and services really cannot work.” Arvin, the migrant camp known as Weedpatch, proved the opposite.

How John Steinbeck Did Research and Described Experts

“History has proven” is a sad tautology, and economics remains a dismal science. That’s why Steinbeck’s joyful art is useful in putting a human face on social and economic abstractions, as The New York Times and Christianity Today did last week. Steinbeck put a human face on every subject when he wrote, and the effort often hurt. He lost his first newspaper job because he got bogged down in the human side of the stories his editor assigned. He researched The Grapes of Wrath in person, by doing, reporting on Dustbowl refugees in the field for the San Francisco Examiner, staying at Arvin to learn how it worked, making mercy runs to migrants stranded by floods in the Central Valley. Of Mice and Men was similarly inspired by actual people and events; as Barbara Heavilin notes, Lennie Small was based on a real person.

Economics remains a dismal science. That’s why Steinbeck’s joyful art is useful in putting a human face on social and economic abstractions.

Years after writing these books Steinbeck had a chance meeting on a train with a boyhood friend from Salinas. By then the author was back in the journalism business, producing a syndicated newspaper column that allowed him personal privilege, which he used, to speak his mind. Tongue in cheek, he tacked the meeting onto a tall-tale column about religion, describing his old friend, now grown, as a “professor of anthropology . . . or some such vermin.” Vermin seems a strong word to describe an expert, even if the friend was in on the joke. On the other hand, the misinterpretation of Steinbeck’s meaning by authorities in Texas, and by an academic in North Carolina, suggests why he used it.

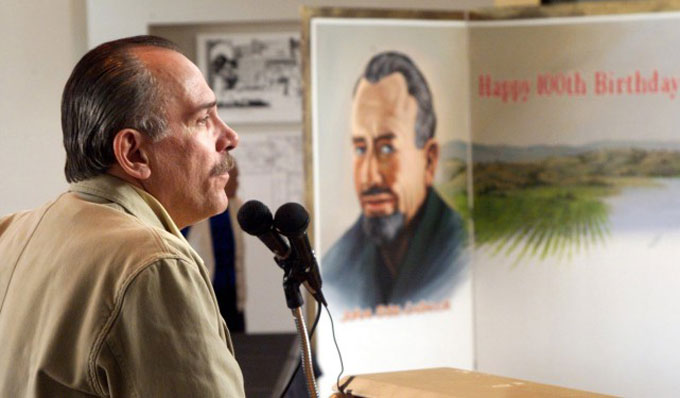

Thomas Steinbeck, John Steinbeck’s Son, Dead at 72

As reported by the New York Times, John Steinbeck’s surviving son, Thomas Steinbeck, died on August 11 in Santa Barbara, California, from cardiopulmonary disease, the condition that contributed to his father’s death at age 66 in 1968. A second Steinbeck son, John Steinbeck IV, died in 1992. Their mother was John Steinbeck’s second wife; the New York Times obituary detailed the course of legal action brought by Thomas Steinbeck and a niece against the non-blood heirs and literary agents of the author, who left the bulk of his estate to his third wife. While noting Thomas Steinbeck’s strong resemblance to his father, the New York Times story failed to mention the Steinbeckian character and literary quality of the younger Steinbeck’s writing, including novels and stories set on the Monterey Peninsula, the region celebrated in his father’s fiction. Also omitted was Thomas Steinbeck’s generosity to the Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University, which issued a statement praising his friendship and support. Robert DeMott, the John Steinbeck scholar who served as the Center’s director in the 1980s, recalled the son’s gift of his father’s typewriter and other personal items, as well as his presence at events honoring John Steinbeck over the years. Robert DeMott’s tribute to Thomas Steinbeck will be published in Steinbeck Review.

AP photograph of Thomas Steinbeck by Richard Green

John Steinbeck House in Salinas, California Receives Award from Trip Advisor Site

John Steinbeck won literary honors during his lifetime, including a Nobel Prize. Now the house where he was born and reared in Salinas, California has received a high accolade from TripAdvisor.com, one of the hospitality industry’s most heavily used consumer websites. People who visited the Steinbeck House restaurant and gift shop during the past 12 months rated their experience as “excellent” or “very good” frequently enough to earn Trip Advisor’s Certificate of Excellence for the thriving Salinas venue. John Steinbeck, who could be critical of business in his writing, would be gratified. Education and enjoyment, not money, motivated members of the Valley Guild to buy the Steinbeck home, restore it, and operate an intimate restaurant, staffed by a professional chef and volunteers servers, where answers to questions about Steinbeck come with the meal. Toni Bernardi, president of the nonprofit organization, explains: “We appreciate our guests and we all strive to honor the memory of John Steinbeck’s life and work.” Today honoring John Steinbeck turns out to be a good way to pay the bills—and garner praise from the hospitality industry—in Salinas, California.

$4.8 Million Gift to John Steinbeck Center Reported By San Jose Mercury News

The April 20, 2016 San Jose Mercury News reports a record-breaking gift to San Jose State University by Martha Heasley Cox, a retired English professor with a love for John Steinbeck. In 1955—the year East of Eden became a movie—Cox arrived in San Jose from Arkansas with a new PhD to work at San Jose State, where she taught courses and organized conferences devoted to Steinbeck, wrote best-selling college textbooks, and invested the proceeds to support her passion for Steinbeck and her university. Her collection of books by and about Steinbeck became the core of the school’s Steinbeck Studies Center, the oldest academic enterprise devoted to the author in America, and she provided start-up funding for the organization, which was named in her honor. According to the San Jose Mercury News story, $3.1 million of Cox’s posthumous gift will fund the center’s Steinbeck Fellows program for young writers, and $1 million will augment the endowment of a lecture series, also bearing her name, that brings major authors—including Norman Mailer, Toni Morrison, and Andre Dubus III—to the San Jose State University campus each year. The balance of Cox’s bequest will support an online database of Steinbeck materials. As noted by the Mercury News, her gift is the largest made by a faculty member in the school’s history.

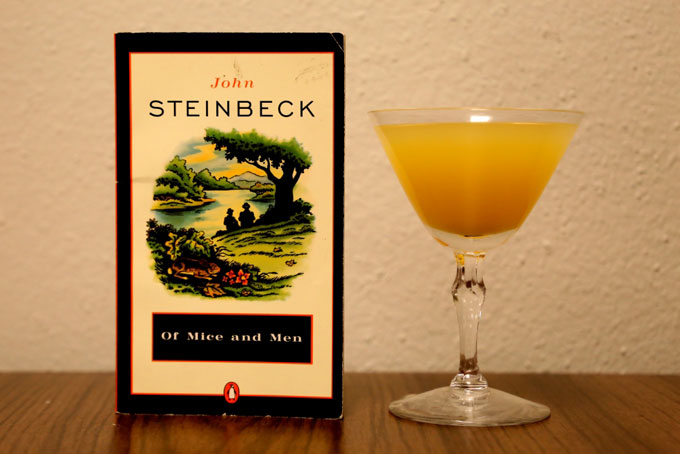

Phoenix, Arizona Toasts Of Mice and Men with a Ward 8

The new production of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men by the Arizona Theatre Company got more than a 10-out-of-10 review from The State Press, the Tempe and Phoenix, Arizona newspaper published by students at Arizona State University. “Books & Booze: ‘Of Mice and Men’ by John Steinbeck,” this week’s column by Carson Abernathy, pairs Steinbeck’s Depression-era work with a Gilded Age cocktail called Ward 8, composed of whiskey, lemon juice, orange juice, and grenadine. Abernathy’s novel concept for making modern fiction palatable to college readers is appealing: he ties the book in question to a drink from the past and rates the writing for style, characterization, cohesiveness, and relevance. (Lolita and The Sun Also Rises were similarly paired and reviewed in recent columns.) We think Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Nabokov would drink to Abernathy’s bright idea.

Photo for The State Press by Johanna Huckeba.

A John Steinbeck Waterfront Park in Sag Harbor’s Future?

John Steinbeck liked Sag Harbor, the Long Island fishing village where he lived and wrote The Winter of Our Discontent, his last novel. He even set the story in Sag Harbor, which in Steinbeck’s time was still the kind of place—like Salinas, his home town—where neighbors stayed on speaking terms and the day’s news could be heard at the downtown coffee shop Steinbeck frequented when he finished his morning writing. Last week the East End Beacon, a Sag Harbor area paper, reported on plans to build a waterfront park named for the writer on property the town is considering condemning. Ed Hollander, the landscape architect hired to propose public use for the land when acquired, “envisions a literary trail, perhaps in collaboration with Sag Harbor’s John Jermain Memorial Library, which would include references to Steinbeck’s work.” In his writing Steinbeck worried aloud about over-development and ecology. So does Sag Harbor’s mayor, Sandra Schroeder. “The village does not need or want more condominiums,” she said. “What we want and need is a transformative park plan that will build on our maritime heritage and protect it for our children, their children, and their children’s children into the future.” Letters of support are welcome.