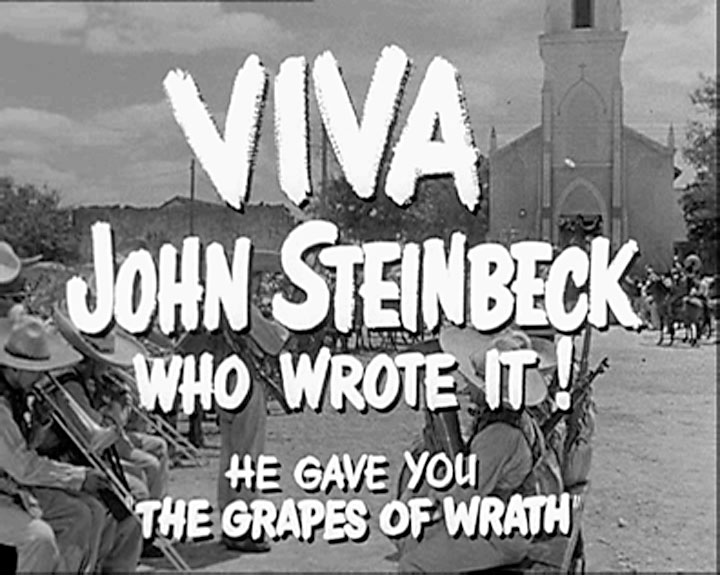

John Steinbeck returned repeatedly to his family roots in Northern Ireland, both in his writing and in his travels. His 1952 novel East of Eden is a paean to his grandfather Sam Hamilton, the Scots-Irish immigrant who settled in California’s Salinas Valley in the 19th century. “I Visit Ireland,” a piece for Collier’s magazine in 1953, describes the writer’s feelings about Sam’s country, and the pilgrimage he made there with his wife Elaine, who took the photo of Steinbeck at the Hamilton family grave site that accompanied the article. “Letters to Alicia,” travel dispatches Steinbeck wrote for syndicated publication in 1965-66, details his final journey, which included Galway, Kerry, and Christmas at John Huston’s Irish castle. John Steinbeck loved the idea of Ireland, and the people of Ireland honored him in return, most recently in a TV series being produced for BBC Two about Northern Ireland and America.

John Steinbeck returned repeatedly to his family roots in Northern Ireland. The people of Ireland honored him in return, most recently in a TV series about Northern Ireland and America.

Carol Robles, the Steinbeck historian who was interviewed for the series by the BBC Two broadcaster William Crawley, convinced Jane MacGowan, the series director, that Steinbeck’s family home in Salinas was the perfect place to shoot the segment on Sam Hamilton, John Steinbeck, and the contribution made by Northern Ireland to the character and culture of California. Before coming to Salinas, Crawley and MacGowan’s crew also visited the site of the labor camp near Bakersfield used by Steinbeck as a model in The Grapes of Wrath. Later, B-roll footage was shot at the Hamilton ranch in King City, the setting for much of the action in East of Eden. Other stops along the Northern Irish trail in America filmed for the new BBC Two series, entitled Brave New World—America, include Massachusetts and Florida—states that are also significant in Steinbeck family history—and the Blue Ridge mountains, where the Scots-Irish spirit celebrated in The Grapes of Wrath lives on in speech and song.

Coming Soon to BBC Two: Brave New World—America

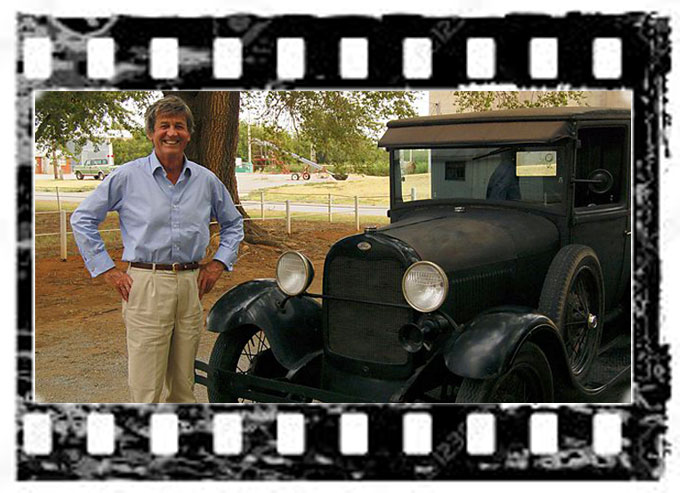

Robles was impressed by the knowledge about John Steinbeck displayed by Crawley and MacGowan when she was interviewed in the intimate reception room of the Steinbeck House on August 11. Afterwards the crew shot background footage in other parts of the home, and Crawley—an ex-minister and break dancer from Belfast with a PhD in philosophy—stopped by the gift shop to chat with volunteers, photograph furniture, and purchase a Steinbeck biography and a first edition of East of Eden. Robles was also impressed by the BBC Two team’s preparation, efficiency, and ability to adapt to change. When MacGowan first contacted Robles on July 25, two weeks before the shoot, the director readily accepted the suggestion to film at the Steinbeck House rather than at the Hamilton ranch as originally planned. Range fires near Salinas prevented filming on Fremont’s Peak, which Steinbeck climbed as a boy and where he contemplates the Salinas Valley in Travels with Charley. Instead, the time was spent shooting footage of the rich farm land around Salinas that created wealth for the town and conflict for the characters in East of Eden.

Carol Robles was impressed by the knowledge about John Steinbeck displayed by William Crawley and Jane MacGowan when she was interviewed, and by their preparation, efficiency, and ability to adapt to change.

“It’s fortunate I didn’t know how famous William Crawley was until they left,” Robles adds. “If I had I would have been more nervous.” With good reason. Crawley has star power, and his broadcast credits are extensive. They include a variety of weighty subjects that also interested John Steinbeck: Blueprint NI, a series on Northern Ireland’s natural history; William Crawley Meets . . . , a current-affairs talk show; Hearts and Minds, a program about politics in Northern Ireland; More Than Meets the Eye, a BBC Two special about Irish folklore; and An Independent People, a program about Ireland’s Presbyterians, the Hamilton family religion. Brave New World—New Zealand, a four-part BBC Two Northern Ireland series that aired in 2014, became the prototype for the series about America. The 2014 series celebrated the contribution made by Northern Ireland to a British colony that, like the United States, benefited from the presence of Scots-Irish immigrants such Sam Hamilton, the Salinas Valley farmer whose grandson won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Photo at Steinbeck House courtesy of Carol Robles