The January 24, 2022 New Yorker magazine puts John Steinbeck in the friendliest possible light—twice in one issue—by exploiting his popularity as an enduring cultural meme for purposes both serious and silly. The pop-music department profile of John Mellenkamp, by Amanda Petrusich, opens with a sober account of the John Steinbeck “in the souls of the people” humanitarian award, which was conferred in 2012 on the Indiana-born singer-songwriter known, like the award’s namesake, for employing art to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Elsewhere in the magazine, the weekly humor column by David Kamp satirizes such Steinbeckian over-seriousness by ascribing qualities to the “Established Creative” type of COVID-era dating partner that Steinbeck might have recognized in himself: “The hetero package comes with a Jaguar E-Type, attractively shelved first editions of John Steinbeck, and a meticulously catalogued collection of rare jazz ’78s.” Fair warning, however. “Extremely successful creative can be more susceptible to messiah complexes, infidelity, [and] using Jessica Chastain as a communications proxy.”

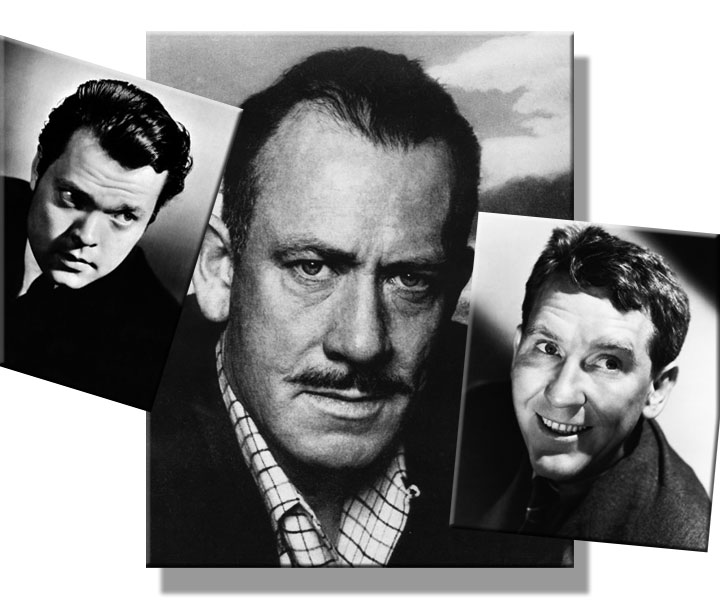

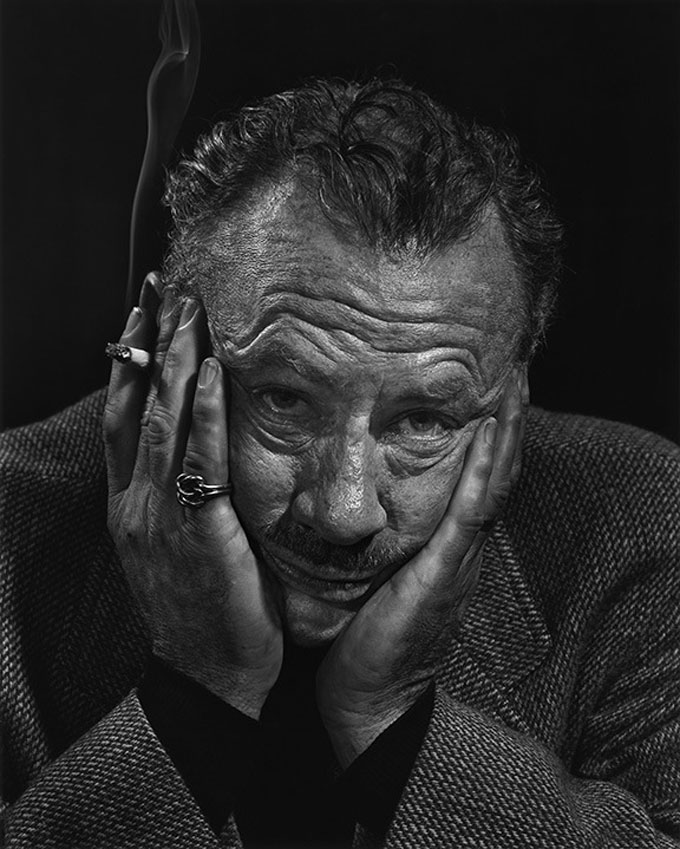

Photo collage: John Steinbeck flanked by serio-comic “Established Creative” co-types, Orson Welles (left) and Burgess Meredith. Not shown: Fred Allen, the comic writer and occasional New Yorker contributor who remained Steinbeck’s close friend until Allen’s death in 1956.