In the fall of 1962 I was at Los Angeles City College writing for the school newspaper. In an article I predicted that a young boxer named Cassius Clay, eventually to be known as Muhammad Ali, would lose his upcoming fight to the crafty Archie Moore. I said the brash, youthful Clay would hobble across the ring at the end of the fight to congratulate the grandfatherly Moore. That led to a surreal encounter with Ali, the three-time heavyweight champion who died on June 3 after battling Parkinson Disease for three decades.

I predicted that a young boxer named Cassius Clay, eventually to be known as Muhammad Ali, would lose his upcoming fight to the crafty Archie Moore.

Los Angeles was a hotbed of prize fighting in the 1960s. The heavyweight division in particular was crowded with talented fighters, many of whose lives would end prematurely. Though Parkinson Disease had a name, chronic traumatic encephalopathy was unfamiliar. Fighters ended up suffering from CTE anyway, and Ali eventually contracted Parkinson Disease, a degenerative condition with multiple causes and no cure.

Los Angeles was a hotbed of prize fighting in the 1960s. The heavyweight division in particular was crowded with talented fighters, many of whose lives would end prematurely.

Few fighters were able to hit Ali in 1962, but head trauma was already, or was becoming, an issue for boxers such as Joey Orbillo, Jerry Quarry, and Eddie Machen. Quarry, saddled with the Great White Hope label, would eventually die of what was described at the time as dementia pugilistica. He became helpless and required round-the-clock care. Machen, a fighter of ballet-like grace, took terrible beatings toward the end of his career, spent time in a psychiatric ward, and fell to his death from an apartment window at age 40.

Few fighters were able to hit Ali in 1962, but head trauma was already, or was becoming, an issue for boxers such as Joey Orbillo, Jerry Quarry, and Eddie Machen.

Orbillo, who fought Quarry while on leave from service in Vietnam, courageously walked point during combat missions–an extremely dangerous duty which he volunteered for because, he reasoned, he was single and his comrades had families. He took such a severe beating from Quarry that he was held back from combat, and another soldier was killed taking the point in his place. Mourning the loss, Orbillo credited Quarry with saving his life.

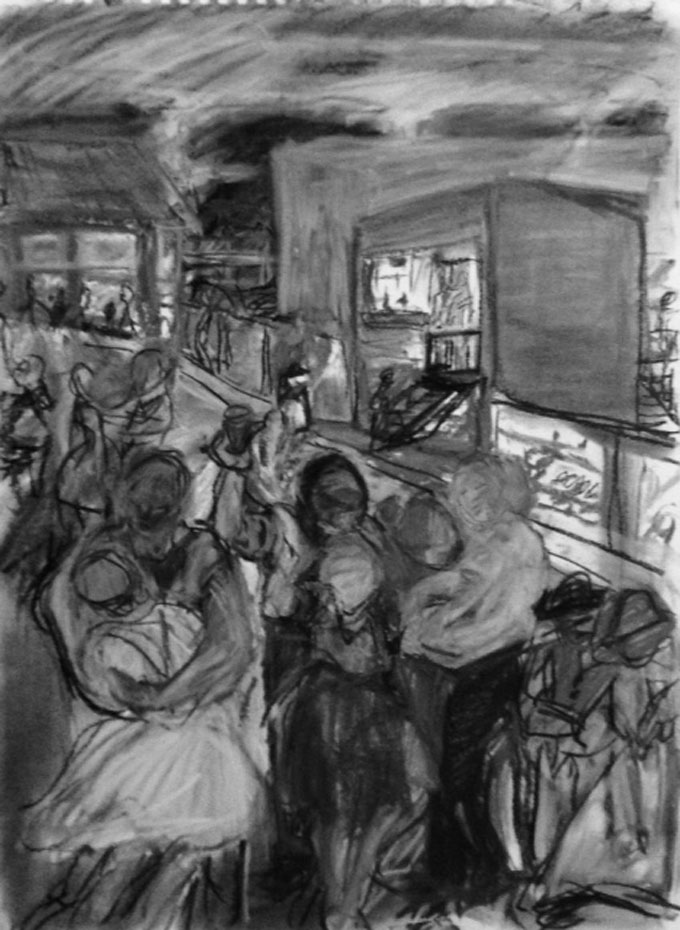

Life at Los Angeles City College in 1962

These tragic stories–and there were many in the heavyweight division–had yet to be told when I wrote about the Ali-Moore fight for the Los Angeles City College paper. Thinking back, I have no idea why I even wrote the column. Ali was of course famous, but there were few signs of his future greatness. And Los Angeles was full of celebrities, some of whom—David Jansen and James Coburn, for instance—could be seen walking across campus or sitting in coffee houses along Vermont Avenue.

These tragic stories had yet to be told when I wrote about the Ali-Moore fight for the Los Angeles City College paper.

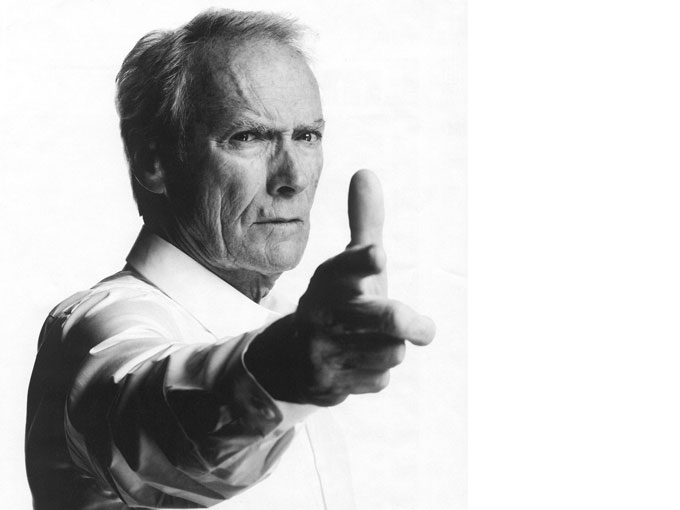

Clint Eastwood, Donna Reed, Paul Winfield–a superb Othello–and Morgan Freeman had taken classes at Los Angeles City College. So had the poet Charles Bukowski, as well as musicians Charles Mingus, John Williams, and Leonard Slatkin. While working at the newspaper I covered a lecture given in the stadium by writer Aldous Huxley. It was one of his last. During my interview with Huxley I realized how terribly ill he was.

The Day Muhammad Ali Walked through the Door

Many of the buildings at Los Angeles City College were relatively new at the time, but the newspaper office was located in a long, narrow prefab with tiny windows. The day my piece on the Ali-Moore fight appeared, I was working on another story when I heard someone chanting “I want Hauk! I want Hauk!” in the distance. The voice was familiar. I stepped outside and saw Ali approaching the building, surrounded by excited students and waving a copy of the paper.

The newspaper office was located in a long, narrow prefab with tiny windows. I heard someone chanting ‘I want Hauk!’ in the distance. The voice was familiar.

“Are you Hauk?” Ali said. “Now don’t lie to me–I can see you are! How could you write this–me lose to Archie Moore? Don’t you know I’m the greatest? Can’t you see I’m pretty? Don’t you know I’m going to give that old man Archie Moore the spanking of his life?”

‘Are you Hauk?’ Ali said. ‘Now don’t lie to me. I can see that you are!’

I replied that it was a columnist’s job to have an opinion. Ali laughed and said that was fine, but he’d prove me wrong. Then he led the students back across the campus. Later he returned to the newsroom alone, sat down, and introduced himself. He was soft-spoken, a bit shy, and quick to smile.

I replied that it was a columnist’s job to have an opinion. Ali laughed and said that was fine, but he’d prove me wrong.

He went on to beat Archie Moore in four rounds, just as he had promised. At the end of the fight I was happy to hear he walked–not hobbled–across the ring to embrace the older man. It bothered me that he shrugged off the win by saying he had beaten “an old man.” Moore deserved better. Ali in those days could be a touch cruel, a quality he wrung from himself and turned into amazing compassion.

Parkinson Disease, Gentleness, and Death

As the years passed Ali began to take the kind of punches that so damaged other fighters, some of them heavyweight champions. Those magnificent heavyweights were killing each other. Then Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson Disease, and one can’t help from feeling it had been hurried along by all of those punches.

As the years passed Ali began to take the kind of punches that had so damaged the other heavyweights, some of them champions.

That he held on for three decades was a testament to Muhammad Ali’s will and resolve, which he called on for causes far beyond the parameters of boxing–and an instinctive gentleness, humor, and kindness, which I had been fortunate enough to experience.

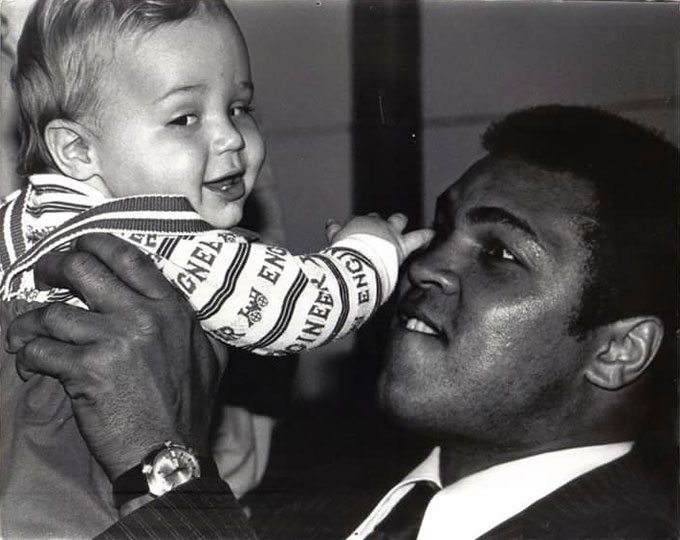

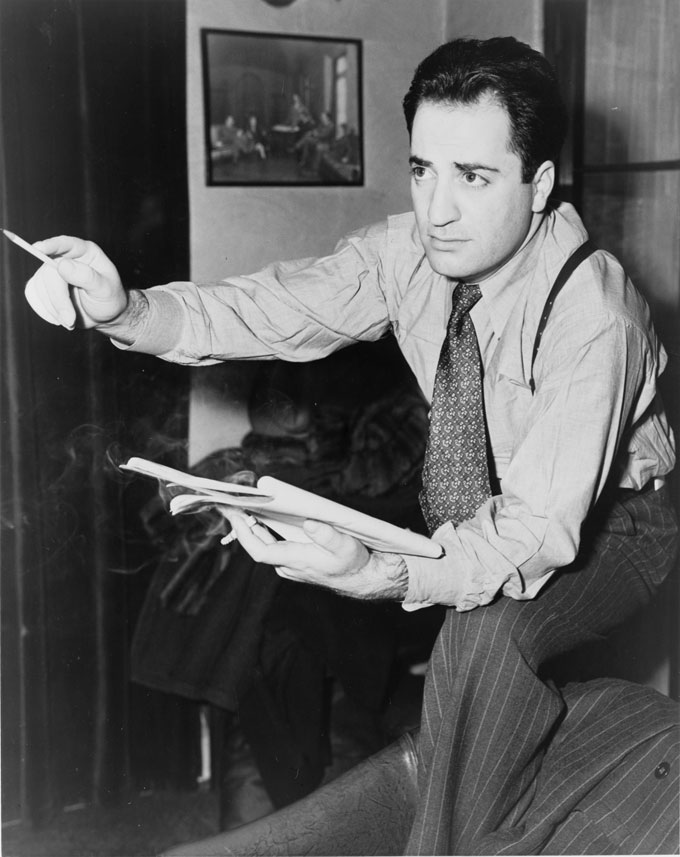

The Photography of Ralph Elliott Starkweather

In a distinguished career ranging the world, Ralph Elliott Starkweather has taken photographs for Life, National Geographic, Gourmet, Smithsonian, and many other magazines. He also had a close relationship with Muhammad Ali, traveling with the late fighter and even recording him moving into a new home.

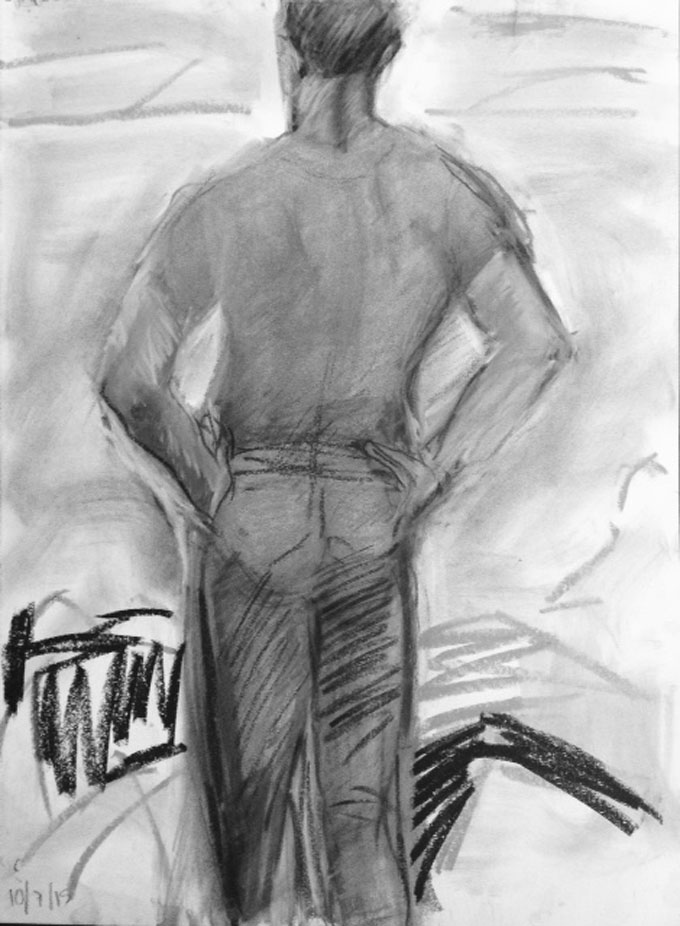

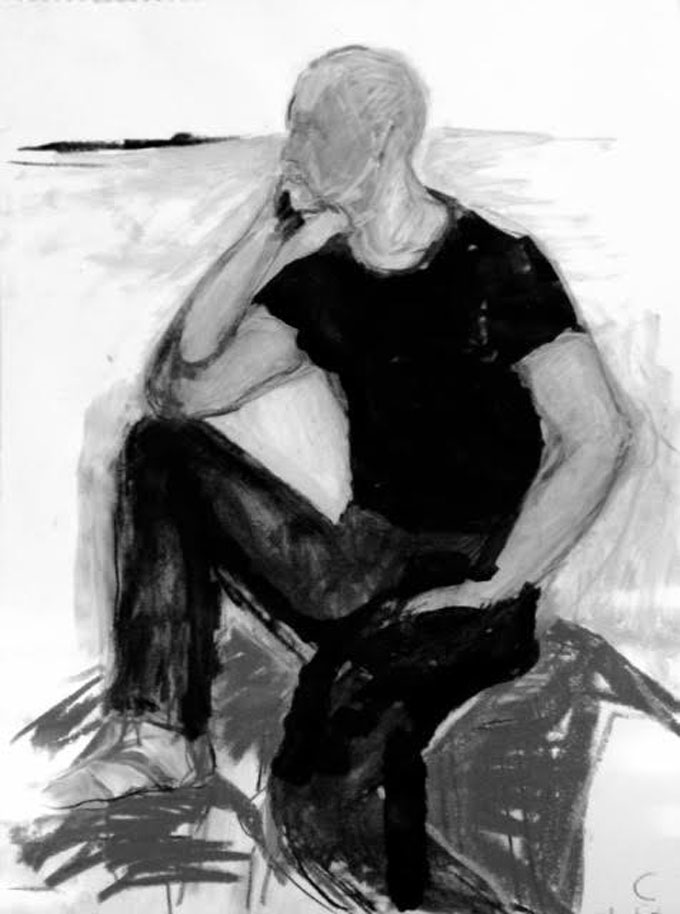

Ralph explains how the lead photo, published here for the first time, was taken: “I went to his home to document his moving into a place called Rossmore in Los Angeles. It was exclusive at the time–guard-gated. My favorite photo because for 10 minutes he was on his own left to his thoughts. In a way like a Black Buddha deep in meditation.”

The other photo is of Ali hoisting Starkweather’s nephew, Chris English, 37 years ago at Los Angeles International Airport. Ali would have been about 37 or 38 at the time, halfway through his life.