It was one of those things easily passed off. It’s something that happened, you found it absurd, then you forgot about it. Years and years later, something occurs and you think of it again, but this time your recollection of the incident verges on the ludicrous.

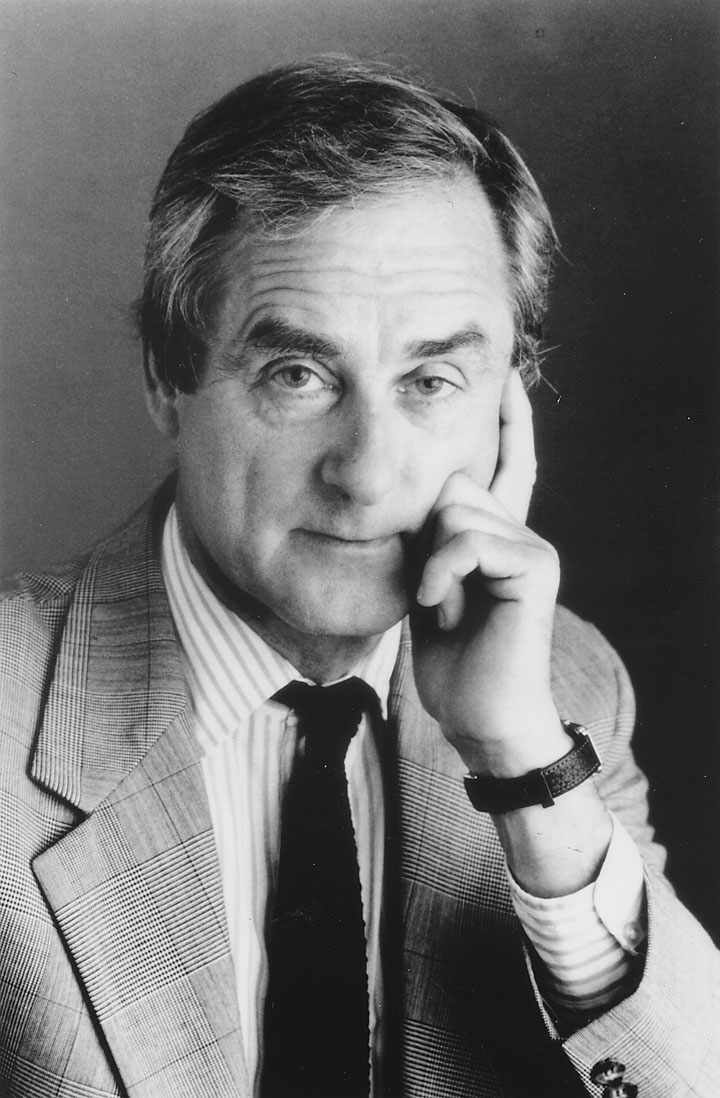

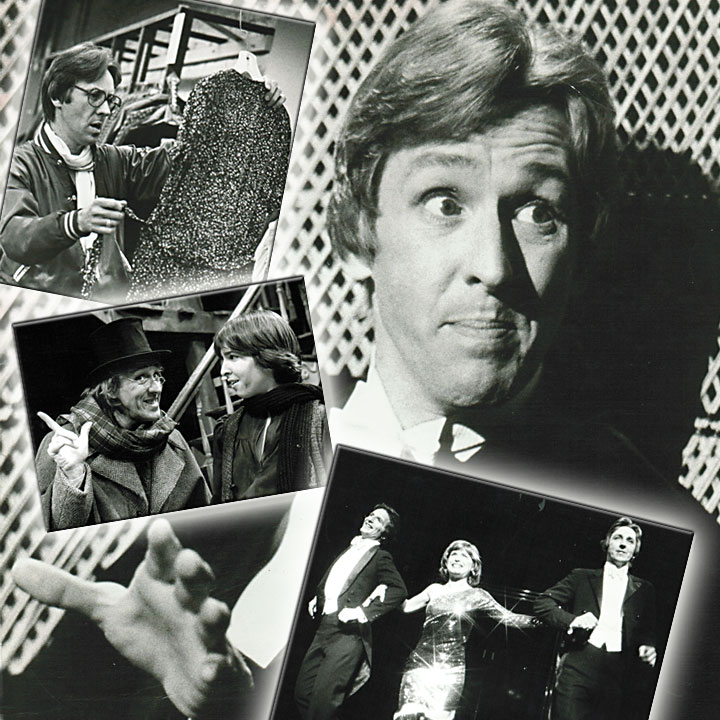

There he was, his hair dishevelled and silver, his posture less straight, his voice a little weak and somewhat shaky: that tall, tough guy, that icon of yesteryear, holding forth before an audience to whom the American Way and Family Values means everything, speaking to an empty chair. It was at the Convention of the Haves, and Clint Eastwood was enjoying his evening dance with the zillionaires.

That’s not how I remember Clint. My memory of him goes back to a time when he was a television cowboy, an actor with dusty boots and clipped speech. It was a summer night at a pub called the Palace on Monterey’s Cannery Row, and he and a couple of his friends were out on the prowl. Muscles showing, smug in their suntanned hides, if there was anything they disliked it was the sight of a bearded, long-haired hippie, and as the Palace invariably had its fair share of them on any given night, Clint and his pals were drawn there as bees to a flower, cats to catnip, or dogs to a hydrant. It was almost a ritual: when Clint Eastwood wasn’t shooting a film in Los Angeles he’d hightail it home to Monterey to gather together his friends and go to Palace to beat up a few hippies.

I was there on one of those nights, sitting in a far corner drinking my Coors and talking to a couple of friends. Looking beyond our table I saw the door open and in they came, Clint and his two sidekicks. They went to the bar, stood there for several minutes, and then, unprovoked, knocked someone with long hair to the floor. No one had said anything, and no one fought back: after all, this was during the Age of Aquarius, and those experiencing the attack by the Eastwood Gang were mellow yellow flower children.

Tables were being overturned, chairs began to fly. No one was resisting. How could they? A frightened young woman sitting opposite me began shaking violently. “Don’t move and we should be all right,” I said, hoping to calm her, and just as I said that I was being lifted bodily from my chair by that same man I saw on television tonight–ironically, as it turns out—speaking to an empty chair.

“What did you say?” he yelled in my face, clutching me by my shirt with one hand and showing me a large fist with the other.

I repeated my words and he loosened the grip on my shirt, dropping me into my chair. He turned away to find someone else to terrorize.

We now jump ahead two or three years, and Clint Eastwood is back in town. But there is no more Palace on Cannery Row. Instead, there is my pub, the Bull’s Eye Tavern in downtown Monterey. All the Palace regulars and more have swarmed to my doors for I offer a great atmosphere and live music and dancing most nights of the week, hard rock sounds and hard rock bands from the area, from San Francisco, and from beyond. Still showing his suntanned beach boy muscles, Clint appears at my door with two or three of his chums. I’m the doorman, standing at the entrance checking IDs and collecting an admission fee for the band. I take one look at Clint and shake my head no. He gives me one of those Dirty Harry looks, and I again shake my head no. Clint moves near.

“John,” he says in a low voice, putting his face down close so I can hear him above the music of the band, “you’re a writer. I respect that. I would never bust up your place.” I let the gang in and he didn’t, but I spent the rest of the evening keeping a wary eye on him. And all the while thinking about the pub this guy went out of his way to help put out of business.

Listening today to Eastwood’s stumbling right-wing blather, it’s pretty obvious that little has changed. Once a bully always a bully, and if it’s not the Palace, it’s the President of the United States he wants to put out of business.

Unless, of course, he decides to show a little respect for Barack Obama as a writer.