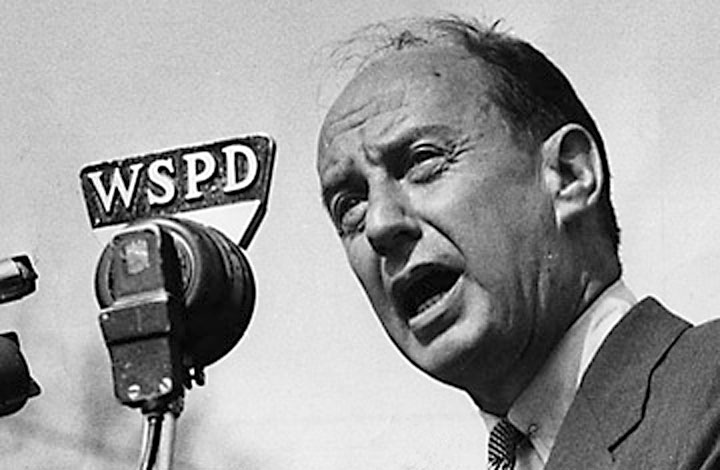

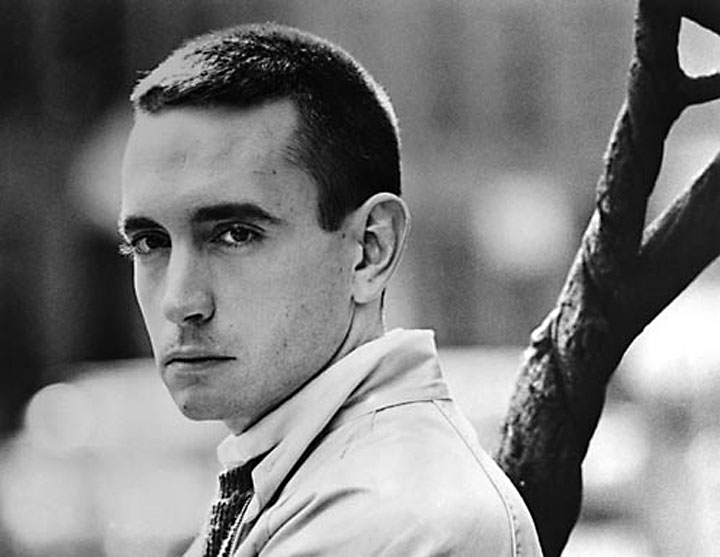

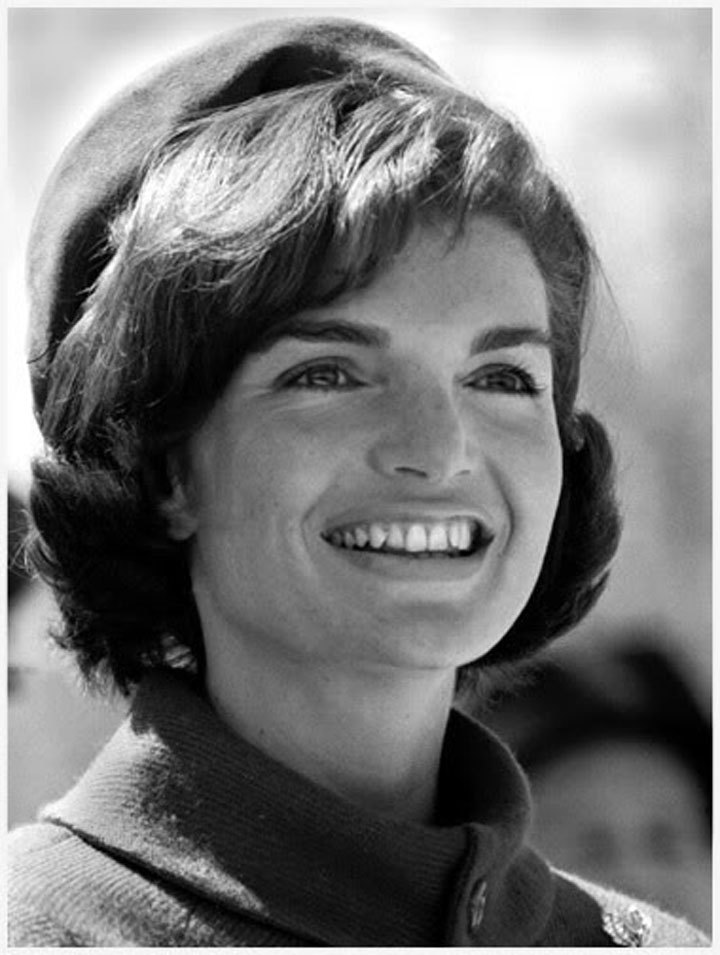

About six weeks after John Steinbeck returned to New York following his 1960 Travels With Charley road trip, he attended John F. Kennedy’s January 20 inauguration in Washington. Steinbeck, then 58, and his wife Elaine shared a limo ride that famously bitter-cold day with Kennedy adviser John Kenneth Galbraith, the celebrated economist, and Galbraith’s wife Catherine. The photo and video are from a documentary produced for an ABC Close Up TV program called Adventures on the New Frontier. In it the Steinbecks and the Galbraiths are seen praising Kennedy’s inauguration speech and making jokes. Although the Galbraiths went to the inaugural ball in Washington that night, the Steinbecks decided to stay warm and watch the affair on TV.

About six weeks after John Steinbeck returned to New York following his 1960 Travels With Charley road trip, he attended John F. Kennedy’s January 20 inauguration in Washington. Steinbeck, then 58, and his wife Elaine shared a limo ride that famously bitter-cold day with Kennedy adviser John Kenneth Galbraith, the celebrated economist, and Galbraith’s wife Catherine. The photo and video are from a documentary produced for an ABC Close Up TV program called Adventures on the New Frontier. In it the Steinbecks and the Galbraiths are seen praising Kennedy’s inauguration speech and making jokes. Although the Galbraiths went to the inaugural ball in Washington that night, the Steinbecks decided to stay warm and watch the affair on TV.

The Missing Last Chapter of Travels with Charley

John Steinbeck describes his and Elaine’s adventures in DC (although he fails to mention John Kenneth Galbraith) in “L’Envoi,” the short chapter he intended to be the ending of Travels with Charley. When the book was released, however, the last chapter—like the Steinbecks at the ball—was missing. It was finally published in 2002 by John Steinbeck’s biographer Jackson Benson and John Steinbeck scholar Susan Shillinglaw in America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction, more than 40 years after Travels with Charley.

How I Discovered the Truth about Travels with Charley

In 2012 I carefully compared Steinbeck’s travel narrative with his actual road trip in my own book, Dogging Steinbeck. Subtitled “How I went in search of John Steinbeck’s America, found my own America, and exposed the truth about Travels with Charley,” Dogging Steinbeck tells how I learned by reading Steinbeck’s own correspondence and his original “Charley” manuscript that his published account contains so many dramatizations, elaborations, and fabrications that it should no longer be considered a work of nonfiction, but fiction. For the latest edition of Travels With Charley, Penguin Group had Jay Parini amend his introduction to warn readers that the book was the work of a novelist and should not be taken literally.