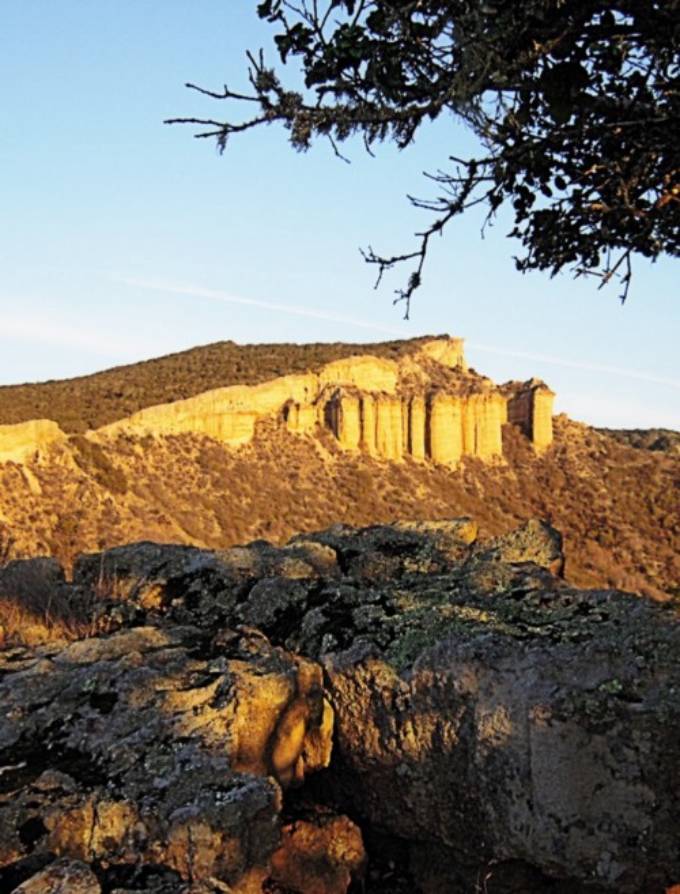

Twenty years ago I took photographs of Monterey County’s Steinbeck Country to present at the Steinbeck Centennial Conference held at Hofstra University in New York. The images, together with expanded text linking them to quotations from the writer’s work, were published as “The Settings for the Stories” in Steinbeck Review, Volume 6. Number 1, Spring 2009. In May 2021, I retraced the Salinas Valley route to see how the landscape looks two decades later. See “John Steinbeck’s Valley of the World Revisited: A Photo Essay” for images like this one, taken of a ranch in “the wilder hills” from Salinas Valley’s historic Old Stage Road.

John Steinbeck’s “Time at Discove” in England’s Camelot Country

“Bruton is the only spot in the world I have refused to see again since John died.”

– Elaine Steinbeck

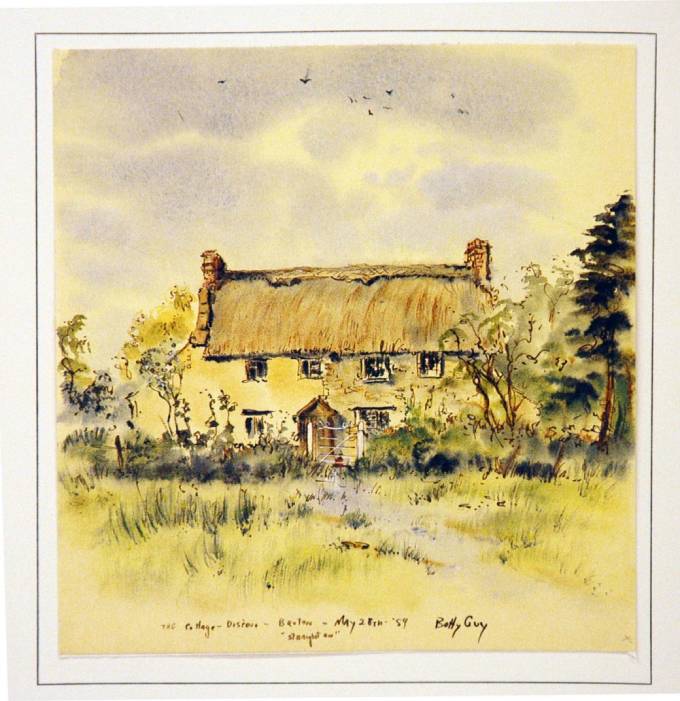

Elaine Steinbeck’s comment in a 1992 letter to the artist Betty Guy refers to the time that she and her husband John Steinbeck spent at Discove Cottage in Bruton, Somerset, England, while he worked on his “reduction of Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur to simple readable prose without adding or taking away anything.” The story behind the story of Steinbeck’s Arthurian quest started 80 years earlier, in California.

The Road from Castle Rock

Steinbeck became fascinated with the legends of King Arthur and the Round Table after his Aunt Molly Martin presented him with a child’s version of the epic tales of chivalry and knighthood on his ninth birthday. He created a secret language based on Malory’s text and, with his sister Mary, played among the exotic eroded turrets of Castle Rock in Corral de Tierra, near Salinas, as their imaginary Camelot. Arthurian themes appeared in Cup of Gold, Tortilla Flat, Of Mice and Men, and many other writings. He began working on Arthur in earnest after completing The Short Reign of King Pippin IV in 1957, work that went through numerous false starts and iterations and consumed Steinbeck for the rest of his life. As late as 1965, in a letter to the actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Steinbeck wrote: “Perhaps you will remember that for at least thirty-five years, and maybe longer, I have been submerged in research for a shot at the timeless Morte d’Arthur. Now Intimations of Mortality warn me that if I am ever going to do it, I had better start right away, like next week.”

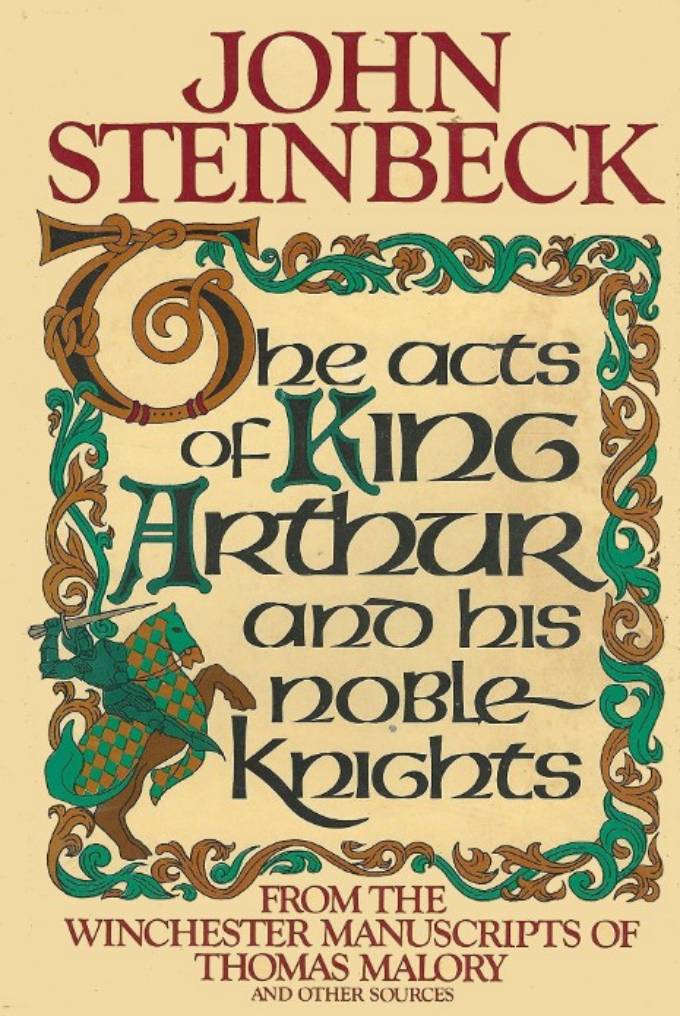

Ultimately Steinbeck failed in his quest to transpose the music of Malory’s language for modern ears. Two unfinished draft manuscripts survive, one created in Somerset, the second written some years after his return. Initially concerned that it would detract from his reputation, Elaine relented to posthumous publication when she realized that her husband had incorporated references to his love for her. Edited by Chase Horton (owner of the Washington Square Bookstore in New York and a friend of his agent Elizabeth Otis), The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knight appeared in 1976. The volume includes an extensive appendix drawn from the author’s letters and journals.

In his correspondence, Steinbeck describes the heights of elation and the depths of despair he experienced while pursuing his search for artistic perfection.

In this correspondence, the writer describes the heights of elation and the depths of despair he experienced while pursuing his search for artistic perfection. One unwavering theme is the sense of joy and contentment in the simple lifestyle he enjoyed during the months spent researching and writing in Discove Cottage, near Bruton in Somerset, England, in 1959. The biographies of Steinbeck by Jackson J. Benson (The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer) and Jay Parini (John Steinbeck: A Biography) recount Elaine’s recollection of a conversation with her husband during his final hours of life. He asked her, “What’s the best time we ever had together?” “The time at Discove,” they agreed. Parini quotes Elaine: “John had discovered something about himself in Discove Cottage.”’ Elaine never returned to Discove, but she remained friendly with the owner, Mrs. Kay Leslie, and she visited the Leslies several times after they sold the cottage to Mr. and Mrs. David Whigham in 1977. Perhaps recalling her husband’s disappointing return to Monterey as recounted in Travels with Charley, Elaine did not wish to disturb the memories of their idyllic sojourn in that humble rural cottage.

Exploring England’s Camelot Country

During 1957 and 1958, the Steinbecks traveled Europe in search of original material. John researched in the Vatican libraries in Rome as he believed Sir Thomas Malory had traveled to Italy as a mercenary. In England they met with Professor Eugene Vinaver, a scholar and authority on the 15th century, and toured many Arthurian locations across the country, including Glastonbury Tor in Somerset, the heart of King Arthur Country, and the medieval replica of the Round Table at Winchester Castle. Stage and screenwriter Robert Bolt (A Man for All Seasons, Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago), who taught English at the nearby Millfield school, introduced them to other ancient English traditions, including cricket and the village pub.

‘I am depending on Somerset to give me the something new which I need,’ wrote Steinbeck.

In July 1958, Steinbeck started work on the translation at his retreat in Sag Harbor, New York, but soon reached an impasse in his search for an appropriate “path or a symbol or an approach.” Believing that he could find this thread in England (“I am depending on Somerset to give me the something new which I need”), he and Elaine crossed the Atlantic again in February 1959. They landed at Plymouth, took delivery of a Hillman Minx estate car (station wagon), and drove to the ancient market town of Bruton. Here they rented Discove Cottage, located for them by Robert Bolt on the estate of Discove House. Steinbeck was so pleased with Bolt’s find that he presented him a gift of the complete thirteen-volume edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

In July 1958, Steinbeck started work on the translation at his retreat in Sag Harbor, New York, but soon reached an impasse in his search for an appropriate “path or a symbol or an approach.” Believing that he could find this thread in England (“I am depending on Somerset to give me the something new which I need”), he and Elaine crossed the Atlantic again in February 1959. They landed at Plymouth, took delivery of a Hillman Minx estate car (station wagon), and drove to the ancient market town of Bruton. Here they rented Discove Cottage, located for them by Robert Bolt on the estate of Discove House. Steinbeck was so pleased with Bolt’s find that he presented him a gift of the complete thirteen-volume edition of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Discove House is a Grade II Listed Building. The two-storey stone house features a projecting porch and a steep thatched roof between coped gables. Although it does exhibit earlier features, much of the structure dates from the 17th century. At 140 feet in length, the house is said to be the longest thatched residence in England. Steinbeck called it an “old manor house,” but Discove was more likely the dower house for the nearby Redlynch Estate of the Earls of Ilchester. A dower house is a residence reserved for the widow when an entailed estate passes on to the older son.

Discove Cottage is a former farm laborer’s dwelling hidden from the road in the fields behind the main house.

Discove Cottage is a former farm laborer’s dwelling hidden from the road in the fields behind the main house. It has two bedrooms upstairs and a kitchen-dining room and a living room downstairs. According to Steinbeck, “It has stone walls three feet thick and a deep thatched roof and is very comfortable . . . . It is probable that it was the hut of a religious hermit. It’s something to live in a house that has sheltered 60 generations.”

The name Discove is believed to derive from a combination of the proper names Dycga or Diga and the Anglo-Saxon word for bedchamber or hut.

The name Discove is believed to derive from a combination of the proper names Dycga or Diga, used by monks 600-800 AD, and the Anglo-Saxon word cove, for bedchamber or hut. In the 1086 AD Doomsday Book of William the Conqueror, it is recorded as Dinescove. The surrounding area has been occupied since ancient times. A possible barrow, or Neolithic burial chamber, has been identified at Redlynch, and a tessellated pavement from the Roman era, 1,000 years before the Conqueror, was uncovered at Discove in 1711.

‘We are right smack in the middle of Arthurian Country.’ wrote Steinbeck. ‘And I feel that I belong here. I have a sense of relaxation I haven’t known for years. Hope I can keep it for a while.’

The Steinbecks settled into rural life quickly. “Elaine is seeding Somerset with a Texas accent,” wrote Steinbeck. “She’s got Mr. Windmill of Bruton saying you-all. At the moment, she is out in the gallant little Hillman calling on the vicar.” As for the task at hand, “If ever there was a place to write the Morte, this is it. Ten miles away is the Roman fort, which is the traditional Camelot. We are right smack in the middle of Arthurian Country. And I feel that I belong here. I have a sense of relaxation I haven’t known for years. Hope I can keep it for a while.”

“Yesterday I cut dandelions in the meadow and we cooked them for dinner last night—delicious,” Steinbeck reported. “And there’s cress in the springs on the hill. But mainly there’s peace—and a sense of enough time.” The praise approached mysticism. “I can’t describe the joy. In the mornings I get up early to have time to listen to the birds. It’s a busy time for them. Sometimes for over an hour I do nothing but look and listen and out of this comes a luxury of rest and peace and something I can only describe as in-ness. And then when the birds have finished and the countryside goes about its business, I come up to my little room to work. And the interval between sitting and writing grows shorter every day.” Elaine agreed: “John’s enthusiasm and excitement are authentic and wonderful to see. I have never known him to have such a perfect balance of excitement in work and contentment in living in the ten years I have known him.”

The grail of modern translation may have eluded Steinbeck, but the months at Discove had been wonderful: ‘this has been a good time—maybe the best we have ever had.’

The idyll was broken in May when Otis and Horton told Steinbeck that they were disappointed with the first section of the manuscript he had submitted to his agents in New York. “To indicate that I was not shocked would be untrue,” replied Steinbeck. “I was.” For the rest of the summer, Steinbeck struggled but failed to find his voice. In September he wrote, “Our time here is over and I feel tragic about it. . . . The subject is so much bigger than I am. It frightens me.” The grail of modern translation may have eluded Steinbeck, but the months at Discove had been wonderful: “this has been a good time—maybe the best we have ever had.”

Discovering Discove Decades After Steinbeck

While visiting friends in the west of England in 2005, my wife and I took a detour to Bruton to see if the cottage still looked as Steinbeck described it. On a cold, wet English October day, the Whighams welcomed us to morning coffee in the richly carved oak-paneled living room of Discove House, their home. The prior owner, Mrs. Leslie, had advised them of the estate’s literary connection. They told us that a crew from the BBC had filmed the cottage several years before for a Steinbeck documentary. They also recounted a bit of the house’s post-Norman history, including the addition of the “new” wing in 1750 to accommodate Lady Ilchester, who did not wish to return to Redlynch in the dark after her weekly bridge game.

It may be a little worse for wear, but the narrow iron gate in the boundary hedge remains. On pushing it open and strolling in the quiet of the enclosed garden, I immediately sensed the peace and contentment that fills those letters of half a century ago.

I gave David Whigham a copy of the National Steinbeck Center visitor guide that features the painting of Discove Cottage by Betty Guy. Steinbeck’s editor, Pascal Covici, had commissioned her to visit Bruton to paint the cottage as a Christmas gift for the Steinbecks in 1959. Seeing the thatched roof in the picture, the Whighams noted that it had been replaced with tiles before they acquired the building. During a pause in the rain, we walked across the lush green meadow to the cottage. The small wooden porch over the front door was gone, and the fledgling cypress tree in the 1959 painting towered over the house in 2005. It may be a little worse for wear, but the narrow iron gate in the boundary hedge remains. On pushing it open and strolling in the quiet of the enclosed garden, I immediately sensed the peace and contentment that fills those letters of half a century ago.

I was delighted to learn that this was the table upon which a literary giant crafted his evocative letters extolling the joys of ‘the time at Discove’ all those decades ago.

David mentioned that he and his wife had acquired all the furniture with the cottage. Mrs. Leslie had told him that it included a work desk and other items purchased by Steinbeck. I was most curious about a table-top draftsman’s board manufactured by Admel Drafting Equipment and supplied by Lawes Rabjohns Ltd. of Westminster. On our return to California, I found several references to the table in Steinbeck’s correspondence with Chase Horton. On April 25, 1959, he wrote, “My table-top tilt board came. Makes a draftsman’s table of a card table. My neck and shoulders don’t get so damned tired.” I contacted Betty Guy in San Francisco to ask if she had noticed a table when she was invited to the writer’s room to sketch from the window. She said she had: “When John asked me up to his room he showed me his slanted work table, so it must have been the draftsman’s table.” I was delighted to learn that this was the table upon which a literary giant crafted his evocative letters extolling the joys of “the time at Discove” all those decades ago. Steinbeck’s work table is currently on display in the Bruton Museum.

David mentioned that he and his wife had acquired all the furniture with the cottage. Mrs. Leslie had told him that it included a work desk and other items purchased by Steinbeck. I was most curious about a table-top draftsman’s board manufactured by Admel Drafting Equipment and supplied by Lawes Rabjohns Ltd. of Westminster. On our return to California, I found several references to the table in Steinbeck’s correspondence with Chase Horton. On April 25, 1959, he wrote, “My table-top tilt board came. Makes a draftsman’s table of a card table. My neck and shoulders don’t get so damned tired.” I contacted Betty Guy in San Francisco to ask if she had noticed a table when she was invited to the writer’s room to sketch from the window. She said she had: “When John asked me up to his room he showed me his slanted work table, so it must have been the draftsman’s table.” I was delighted to learn that this was the table upon which a literary giant crafted his evocative letters extolling the joys of “the time at Discove” all those decades ago. Steinbeck’s work table is currently on display in the Bruton Museum.

This article has been adapted by the author from a version originally published in the Fall 2006 issue of Steinbeck Review. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations attributed to Steinbeck are from The Acts of King Arthur and his Noble Knights, ed. Chase Horton (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), and Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (New York: Viking, 1975).

Talk on Ernest Hemingway Illuminates John Steinbeck

When Ernest Hemingway died, John Steinbeck suspected suicide and praised Hemingway’s writing, but knew Hemingway had disparaged his, viewing him as a literary competitor. Michael Katakis, the award-winning photographer and cultural critic who divides his time between Paris and Carmel, spoke recently about becoming Hemingway’s literary executor, editing Ernest Hemingway: Artifacts from a Life, and putting Hemingway and Steinbeck in comparative perspective as contrasting authors who remain popular with contemporary readers despite their differences. The recorded conversation took place on January 31, 2019 at the Carmel Public Library. Like the photography of Yousuf Karsh, the light it sheds on Ernest Hemingway also extends to John Steinbeck, whose life is the subject of a new biography by William Souder—scheduled for publication in 2020—that may comment further on the relationship of two figures with more in common than either ever acknowledged.—Ed.

An Evening’s Conversation: Ernest Hemingway and Traveling the World from Harrison Memorial Library on Vimeo.

New Light on John Steinbeck

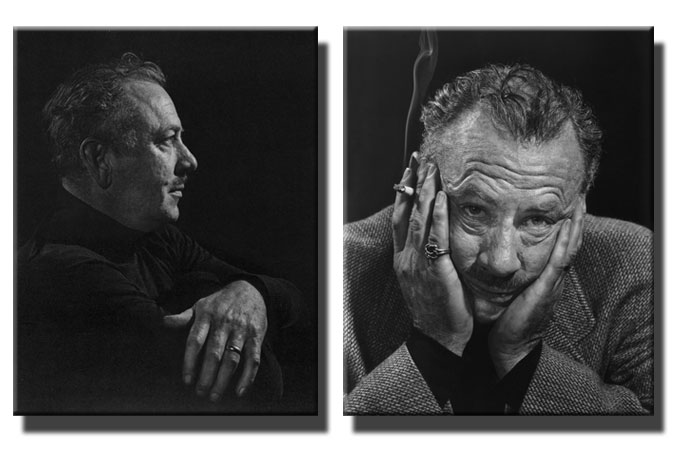

According to Yousuf Karsh it was Art Buchwald who made the introduction that led to John Steinbeck’s June 15, 1954 sitting in Paris with the 40-something photographer from Ottawa. An amateur film maker who disliked having his photo taken but liked pictures and people with panache, Steinbeck warmed to Karsh, a Boston-trained Canadian immigrant whose black and white portraits of Winston Churchill and other public figures had already made him famous. Karsh’s European elegance and wit won over the author of East of Eden, distracted and depressed by events following the publication of the novel into which he’d folded the story of his mother’s family, the Scotch-Irish Hamilton clan. But it was his father’s family history that connected him to Karsh, an Armenian of Arab descent whose parents escaped Turkey through Syria during the 1914 Armenian genocide that signaled the final end of the Ottoman Empire. A half-century earlier, in the 1850s, Steinbeck’s Prussian-English grandparents made a similar escape following an attack on their missionary compound by Arab marauders in Ottoman-controlled Palestine. The ancestral sagas of both men included flight from the Holy Land, haven in New England, and secular self-reinvention against a background of 19th century marriage, migration, and religious mania. Recent detective work has unearthed new details about Steinbeck’s 19th century roots and 20th century connections, including the true story of his family’s religious conversion and the facts behind the fictions regarding his time at Stanford. Starting in 2019, these and other topics will be explored in a new series of essay posts at Steinbeck Now that put new light on John Steinbeck, like a portrait by Yousuf Karsh.

Steinbeck Made 1968 Stick

This AP image from John Steinbeck’s December 23, 1968 funeral, at St. James Episcopal Church in New York, appears in a recent Ravalli Republic photo essay that attempts the question, “What was it about 1968 that shook the foundations of American life, defining the end of one generation and the beginning of another?” Given the competition and the source—a county paper in Hamilton, Montana—it’s remarkable that Steinbeck’s death made the cut for a year characterized by assassination, war, and the election of a president who later resigned in disgrace. Located on the Wyoming border, Hamilton, Montana wasn’t named for the Irish grandfather immortalized in East of Eden. But, like Salinas, it’s the county seat, and it’s about the size Salinas was when Sam Hamilton died and Steinbeck was born. Steinbeck celebrated the beauty of Montana in Travels with Charley, and the life of towns like Hamilton in America and Americans. If his death still sticks in the minds of Ravalli Republic readers in this momentous year, gratitude rather than surprise would be the right response.

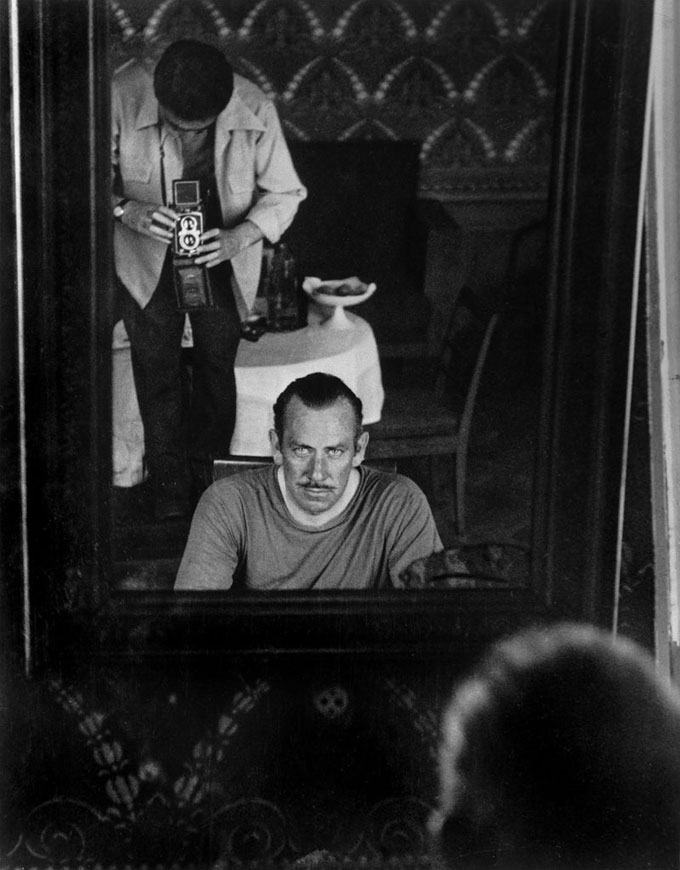

New Republic Updates John Steinbeck and Robert Capa’s Russian Journal in Pictures

Like John Steinbeck’s 1940 expedition to Baja, California with the marine biologist Ed Ricketts, his 1947 trip to Russia with the war photographer Robert Capa yielded a book that reveals as much about the relationship of the co-authors as it does about the subject. Like Ricketts, Steinbeck’s collaborator in writing Sea of Cortez, Capa was Steinbeck’s boon companion and opposite, equally accomplished and adventurous but lighter on his feet and better with women and strangers. A photo essay published this week in New Republic, 70 years after the publication of A Russian Journal, displays a selection of Capa’s black-and-white images next to color photos taken by Thomas Dworzak when he and Julius Strauss recapped the trip recorded in A Russian Journal to show how Russia has changed since 1947. Steinbeck enjoyed the company of everyday Russians, who weren’t that different from Americans when encountered face-to-face. He also enjoyed Robert Capa, as shown in Capa’s photo of Steinbeck looking at their reflection, a mirror of the relationship revealed in A Russian Journal.

Photograph by Robert Capa courtesy International Center of Photography/Magnum.

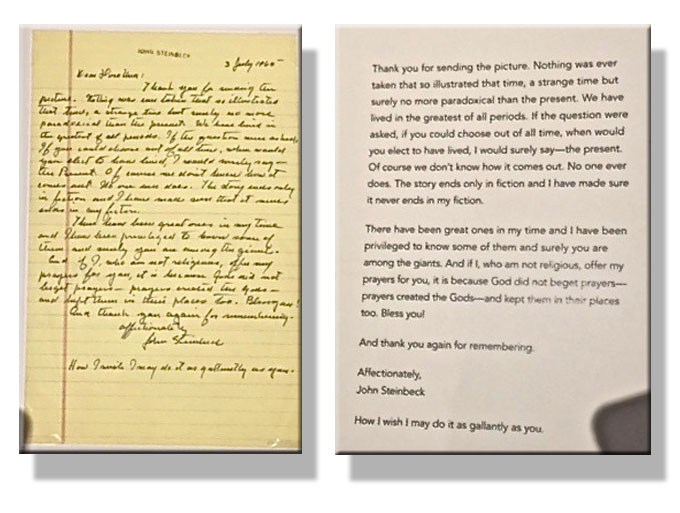

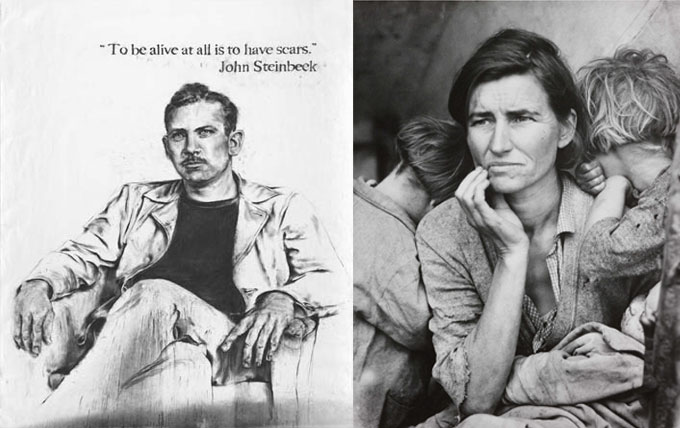

Bless You! John Steinbeck’s Letter to Dorothea Lange

Shortly before the show closed on August 27, my wife and I drove from our home in Salinas to the Oakland Museum of California to see Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, an exhibit devoted to the documentary photographer whose images of the 1930s quickly became associated with John Steinbeck and The Grapes of Wrath. Like Steinbeck’s novel, Lange’s Great Depression pictures have become symbols of the suffering of farmland Americans displaced by joblessness, drought, and despair. Less familiar but equally powerful are the events recorded in Lange’s photos of Japanese-Americans “relocated” from their homes to internment camps after Pearl Harbor—an executive order signed by President Roosevelt that Steinbeck and Lange both questioned at the time. Lange’s internment images were so evocative, and so damning, that most of them were confiscated by the government and suppressed, even after the war. Also on display was the letter John Steinbeck wrote to Dorothea Lange on July 3, 1960, looking back on their friendship and the events of the Great Depression and ending with this deeply personal statement, half-confession and half-benediction: “And if I, who am not religious, offer my prayers for you, it is because God did not beget prayers—prayers created the Gods—and kept them in their places too. Bless you!”

Yale University Brings the Great Depression Home

Yale University has launched Photogrammar, a handy interactive website that pairs images of the Great Depression from the Library of Congress photo archive with the photographers who took them and the places where they were taken. Like The Grapes of Wrath, the photographs of Dorothea Lange and others were intended to educate, engage, and convince average Americans that the poor were human, too. Commissioned by the U.S. Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information and assembled between 1935 and 1945, the 170,000-piece photo archive—like the California migrant camp celebrated by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath—provides eloquent testimony of government’s power to do good, despite naysayers from the right, when disasters occur. The ambitious Yale University project was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, a 40-year old federal agency that will disappear if Donald Trump’s proposal to defund the arts and humanities—along with safety-net social programs like Meals on Wheels—is approved by Congress.

Rare Photos of John Steinbeck Illustrate New Academic Research Articles

Rare photos of John Steinbeck from the collection of the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University—including this 1945 image of Steinbeck with wife Gwyn and son Thom—complement an array of academic research articles by Robert DeMott and others in the Winter 2016 issue of Steinbeck Review. The journal is a publication of Penn State Press and appears twice a year. Barbara A. Heavilin is the editor-in-chief, and Nick Taylor is the executive editor. Photo courtesy Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies. To subscribe to the journal, visit the Penn State Press site’s Steinbeck Review page.

East of Eden: A Pilgrimage in Pictures to John Steinbeck’s Salinas, California

East of Eden, the autobiographical novel John Steinbeck described as his “marathon book,” portrayed Salinas, California at the turn of the 20th century as a small place with big problems. Steinbeck characterized the culture of the town where he was born in 1902 even more critically in “Always Something to Do in Salinas,” an essay he wrote for Holiday Magazine three years after completing East of Eden. His description of Salinas sins and shortcomings in “L’Affaire Lettuceburg” was so negative that he recalled the manuscript and prevented its publication. Eventually Salinas forgave the injury, naming the town library in Steinbeck’s honor and building a center devoted to his life and work on Main Street. But main street Salinas, California fell on hard times after John Steinbeck left, the victim of suburban sprawl and competition from Monterey, Carmel, Pebble Beach, and Pacific Grove, where Steinbeck preferred to live and write. With this in mind, I made a pilgrimage with my camera to record changes in Salinas since East of Eden and to discover how Steinbeck is remembered today, almost 50 years after his death.

John Steinbeck’s Salinas, California Starts on Main Street

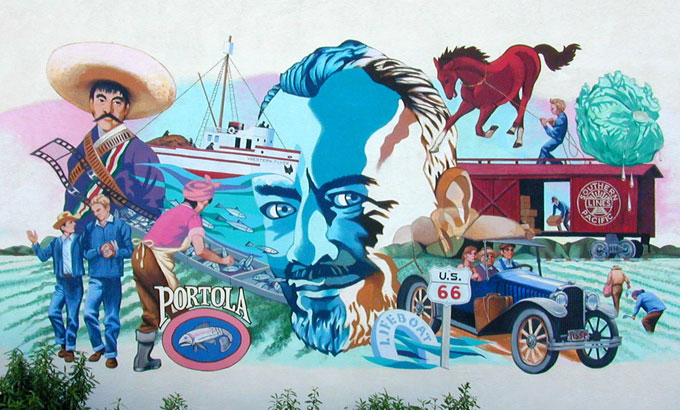

I started at the National Steinbeck Center, built 18 years ago at One Main Street to house the John Steinbeck archive, attract visitors, and educate residents about the town’s most famous son. Inside, I relived scenes from East of Eden and other works through video clips, stage sets, and documents about Steinbeck’s boyhood in Salinas. Guided by Steinbeck’s words—and by murals, plaques, and signs memorializing his life—I set out to explore the links to the past provided by buildings that survive from Steinbeck’s era.

Guided by Steinbeck’s words—and by murals, plaques, and signs memorializing his life—I set out to explore the links to the past provided by buildings that survive from Steinbeck’s era.

Seen from the center’s front steps, Steinbeck’s craggy visage dominates the mural on the building across Central Avenue where the grocer and butcher patronized by his mother did business 100 years ago. Looking down Main Street, I saw Mount Toro, the backdrop for The Pastures of Heaven, the stories about trouble in paradise written by Steinbeck 20 years before East of Eden. Mentally uprooting trees and planters and replacing sleek SUVs with boxy black Fords, I tried to imagine Main Street as it appeared to Steinbeck when he was writing his stories. The effort was complicated by a pair of modern structures built to bring people back to town: the Maya Cinema multiplex and the world headquarters of Taylor Farms, edifices that face one another, literally and symbolically, across the Main Street divide.

Life Along John Steinbeck’s Central Avenue Then and Now

From One Main Street I retraced the steps of Adam Trask, who in East of Eden “turned off Main Street and walked up Central Avenue to number 130, the high white house of Ernest Steinbeck.” Today the Central Avenue home where John Steinbeck was born is number 132, and the white exterior of Steinbeck’s era has been replaced by cream, blue, and tan tones highlighting the Queen Anne-style frills and furbelows. Inside, high ceilings, dark polished wood, and Victorian decor greet lunch patrons at the Steinbeck House restaurant, operated by the nonprofit organization that purchased the home after it passed through stages of ownership and decay following the death of Steinbeck’s father in 1935.

Today the Central Avenue home where John Steinbeck was born is number 132, and the white exterior of Steinbeck’s era has been replaced by cream, blue, and tan tones highlighting the Queen Anne-style frills and furbelows.

A Steinbeck House volunteer greeted me in the room where the writer was born; the maternal bed, a finely crafted period piece, can be seen in the gift shop downstairs. I dined next to the fireplace where Olive Steinbeck, a schoolteacher, nourished John and his three sisters on a diet of classical music and great books that fed the imagination of the budding author, who observed life on Central Avenue from the gable window of his bedroom. “I used to sit in that little room upstairs,” he recalled, “and write little stories.” Parts of The Red Pony and Tortilla Flat were written while Steinbeck tended his mother at home before her death in 1934. “The house in Salinas is pretty haunted now,” he confided to a friend. “I see things walking at night that it is not good to see.”

Olive Steinbeck, a schoolteacher, nourished John and his three sisters on a diet of classical music and great books that fed the imagination of the budding author, who observed life on Central Avenue from the gable window of his bedroom.

A block away, Steinbeck spent happy hours playing with the Wagner brothers, whose mother Edith, an aspiring writer in whom Steinbeck confided his own ambition, provided material for Steinbeck’s story “How Edith McGillicuddy Met R. L. S.” One brother was involved in the throwing of a roast beef through the glass door of city hall, an act attributed to Steinbeck, who recalled that “[Max] worked so hard and I got all the credit.” Steinbeck and the Wagner boys eventually made their way to Hollywood, where Jack helped with script writing for the film adaptation of Steinbeck’s short novel The Pearl. Max, an actor, played bit parts in movie versions of The Grapes of Wrath and The Red Pony. Jack recruited Steinbeck to help with screenwriting for the 1945 motion picture A Medal for Benny. Max also participated.

In Trouble as a Boy and as a Man in Salinas, California

At 120 Capitol Street, not far from Central Avenue, Roosevelt Elementary School replaced the grammar school that John Steinbeck and the Wagner brothers attended. The school is depicted somberly in East of Eden (“the windows were baleful; and the doors did not smile”) and in the journal Steinbeck kept while writing the novel (“I remember how grey and doleful Monday morning was. . . . What was to come next I knew, the dark corridors of the school”). Steinbeck’s ambivalent feelings about schooldays in Salinas failed to improve with time. Once he was famous, he objected to the idea of naming a school in his honor: “If the city of my birth should wish to perpetuate my name clearly but harmlessly, let it name a bowling alley after me or a dog track or even a medium price, low-church brothel – but a school – !”

Steinbeck’s ambivalent feelings about schooldays in Salinas failed to improve with time.

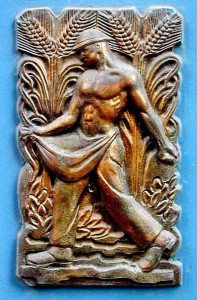

Unlike his pals up the street, John Steinbeck’s parents respected the social and political order of Salinas, the seat of Monterey County. Steinbeck’s father served as county treasurer, and law-abiding pioneer faces stare down from the walls of the town’s Art Moderne courthouse today. Like bas-relief marble panels and bronze door embellishments that celebrate the agricultural workers immortalized in Steinbeck’s fiction, they are the work of Joe Mora, a WPA artist. Steinbeck gathered material for East of Eden at the Art Moderne newspaper building across the street; he played basketball and attended his senior prom at the nearby Troop C Armory building, “where men over fifty . . . snapped orders at one another and wrangled eternally about who should be officers.”

Unlike his pals up the street, John Steinbeck’s parents respected the social and political order of Salinas, the seat of Monterey County. Steinbeck’s father served as county treasurer, and law-abiding pioneer faces stare down from the walls of the town’s Art Moderne courthouse today. Like bas-relief marble panels and bronze door embellishments that celebrate the agricultural workers immortalized in Steinbeck’s fiction, they are the work of Joe Mora, a WPA artist. Steinbeck gathered material for East of Eden at the Art Moderne newspaper building across the street; he played basketball and attended his senior prom at the nearby Troop C Armory building, “where men over fifty . . . snapped orders at one another and wrangled eternally about who should be officers.”

Steinbeck’s father served as county treasurer, and law-abiding pioneer faces stare down from the walls of the town’s Art Deco-style courthouse today.

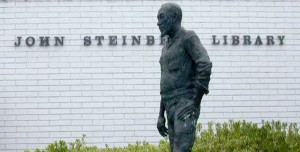

Like Main Street viewed from the National Steinbeck Center, Lincoln Avenue in downtown Salinas is dominated by an imposing image of John Steinbeck, this in the form of the life-size statue installed outside the public library that now bears Steinbeck’s name. Inside the modest brick building I browsed the wealth of Steinbeck books, articles, and clippings accumulated over decades by scholars, friends, and fans. Steinbeck wasn’t always popular with librarians or readers, however. According to Dennis Murphy, the son of a Steinbeck friend and neighbor, angry locals burned copies of The Grapes of Wrath at the corner of San Luis and Main Street. The venue for their act of rage was the Carnegie Library, since torn down, where according to Steinbeck, an unsympathetic librarian “remarked that it was lucky my parents were dead so that they did not have to suffer this shame.”

Like Main Street viewed from the National Steinbeck Center, Lincoln Avenue in downtown Salinas is dominated by an imposing image of John Steinbeck, this in the form of the life-size statue installed outside the public library that now bears Steinbeck’s name. Inside the modest brick building I browsed the wealth of Steinbeck books, articles, and clippings accumulated over decades by scholars, friends, and fans. Steinbeck wasn’t always popular with librarians or readers, however. According to Dennis Murphy, the son of a Steinbeck friend and neighbor, angry locals burned copies of The Grapes of Wrath at the corner of San Luis and Main Street. The venue for their act of rage was the Carnegie Library, since torn down, where according to Steinbeck, an unsympathetic librarian “remarked that it was lucky my parents were dead so that they did not have to suffer this shame.”

Edifices in East of Eden and The Winter of Our Discontent

Some Main Street storefronts are now covered by stucco facades. The surface of one, a six-story bank at the corner of East Alisal and Main Street, is faced with Art Deco terracotta tiles; others hold memories that were painful to John Steinbeck and his family. Ernest Steinbeck’s fledgling feed store at 332 Main Street failed when cars replaced horses. “Poor Dad couldn’t run a store,” Steinbeck wrote in his journal—“he didn’t know how.” Steinbeck fictionalized the failure of his father’s store in The Winter of our Discontent, the semi-autobiographical novel he set in Sag Harbor, New York, a small town that feels like early 20th century Salinas when you read the book now.

Steinbeck fictionalized the failure of his father’s store in the semi-autobiographical novel he set in Sag Harbor, New York, a small town that feels like early 20th century Salinas when you read the book now.

At the Cherry Bean Coffee Shop, a thriving concern occupying part of the site where Ernst Steinbeck opened his store, I dallied over a “Steinbeck brew” and listened to regulars discuss issues of the day, just as Steinbeck did at the main street Sag Harbor coffee shop when he was writing The Winter of Our Discontent. As noted in “L’Affaire Lettuceburg,” Salinas was less democratic in Steinbeck’s time, with “cattle people” at the top of the social stratification he satirized in “Always Something to Do in Salinas.” “Sugar people joined Cattle People in looking down their noses” at lettuce-growers, he recalled in 1955. “These Lettuce People had Carrot People to look down on and these in turn felt odd about associating with Cauliflower People.” Today, complaints heard at the Coffee Bean Shop on Main Street in Salinas revolve around “Silicon People,” commuters with high-paying tech jobs who are inflating home prices.

Salinas was less democratic in Steinbeck’s time, with “cattle people” at the top of the social stratification he satirized in “Always Something to Do in Salinas.”

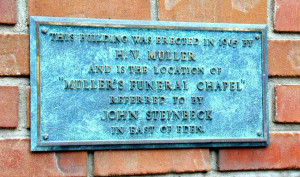

Muller’s Funeral Chapel, another East of Eden landmark, is commemorated with a plaque dedicated to H.V. Muller at 315 Main Street, where John Steinbeck’s mother was prepared for burial in 1934. Today a beauty parlor occupies the space at 242 Main Street where Bell’s Candy Store stood back in 1917, when Steinbeck was a teenager and “the rage was celery tonic.” According to the proprietor at the time, “John was a good boy, but you had to keep your eye on him around the candy!” Across Main Street from Bell’s, Of Mice and Men played at the Exotic Fox Californian Theater when the movie—the first ever made from a book by Steinbeck—opened in 1939.

Muller’s Funeral Chapel, another East of Eden landmark, is commemorated with a plaque dedicated to H.V. Muller at 315 Main Street, where John Steinbeck’s mother was prepared for burial in 1934. Today a beauty parlor occupies the space at 242 Main Street where Bell’s Candy Store stood back in 1917, when Steinbeck was a teenager and “the rage was celery tonic.” According to the proprietor at the time, “John was a good boy, but you had to keep your eye on him around the candy!” Across Main Street from Bell’s, Of Mice and Men played at the Exotic Fox Californian Theater when the movie—the first ever made from a book by Steinbeck—opened in 1939.

Today a beauty parlor occupies the space at 242 Main Street where Bell’s Candy Store stood back in 1917, when Steinbeck was a teenager and “the rage was celery tonic.”

Generations of agricultural wealth in Salinas, California built banks at the four corners of Gavilan and Main streets and held strong views about John Steinbeck. Reporting on local reaction to The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck wrote: “The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad.” Today the four banks are gone and food and antiques are sold in temples where money was once dispensed in an attitude of quiet reverence captured by Steinbeck in East of Eden. Cal withdraws 15 crisp new thousand-dollar bills, and Kate deposits her whorehouse earnings, in the Monterey County Bank building at 201 Main Street. The vaulting structure, recently restored, may also have been the inspiration for the cathedral-like bank that Ethan Hawley decides to rob in The Winter of Our Discontent. Forty years after Steinbeck’s last novel, it served as the location for Bandits, a movie starring Bruce Willis.

Generations of agricultural wealth in Salinas, California built banks at the four corners of Gavilan and Main streets and held strong views about John Steinbeck. Reporting on local reaction to The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck wrote: “The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad.” Today the four banks are gone and food and antiques are sold in temples where money was once dispensed in an attitude of quiet reverence captured by Steinbeck in East of Eden. Cal withdraws 15 crisp new thousand-dollar bills, and Kate deposits her whorehouse earnings, in the Monterey County Bank building at 201 Main Street. The vaulting structure, recently restored, may also have been the inspiration for the cathedral-like bank that Ethan Hawley decides to rob in The Winter of Our Discontent. Forty years after Steinbeck’s last novel, it served as the location for Bandits, a movie starring Bruce Willis.

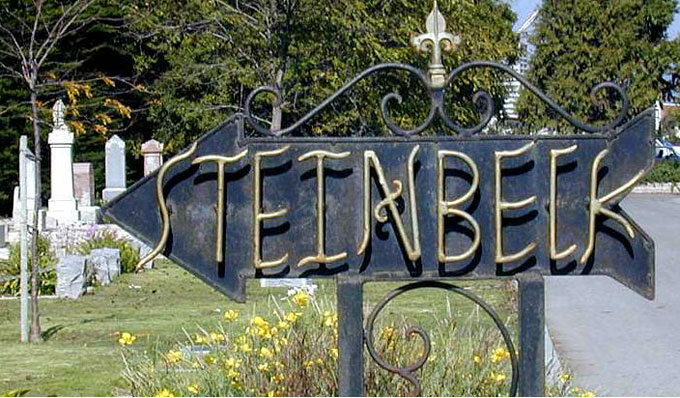

Main Street South to John Steinbeck’s Final Destination

Returning to my car, I left Main Street and turned onto Market (formerly Castroville) Street, the setting for several scenes in East of Eden. “Two blocks down the Southern Pacific tracks cut diagonally,” Steinbeck recalls in the novel: “Over across the tracks down by Chinatown there’s a row of whorehouses.” Driving to the Garden of Memories Memorial Park west of town, I found the simple bronze plaque marking Steinbeck’s final resting place, the end point of my pilgrimage to Salinas, California. Nearby, major players in Steinbeck’s life and fiction—including his wife Elaine, his grandfather Sam Hamilton, and the aunts and uncles celebrated in East of Eden—cohabit peacefully in “that dear little town” where the imagination and conscience of John Steinbeck were kindled a century ago.

This is an updated version of an article published in the Fall 2001 issue of Steinbeck Studies. Our thanks to Carol Robles for correcting several factual errors introduced in the editing process. The Garden of Memories, located southeast of downtown Salinas, contains more than one Hamilton family plot. The headstone shown here is not the one marking the site of John Steinbeck’s ashes. The burning of The Grapes of Wrath in Salinas is attested in various sources, including an interview with the writer Dennis Murphy, the grandson of the Salinas physician who treated Steinbeck as a boy. The Murphy interview is one of a number available to Steinbeck scholars and students in the National Steinbeck Center archive.—Ed.