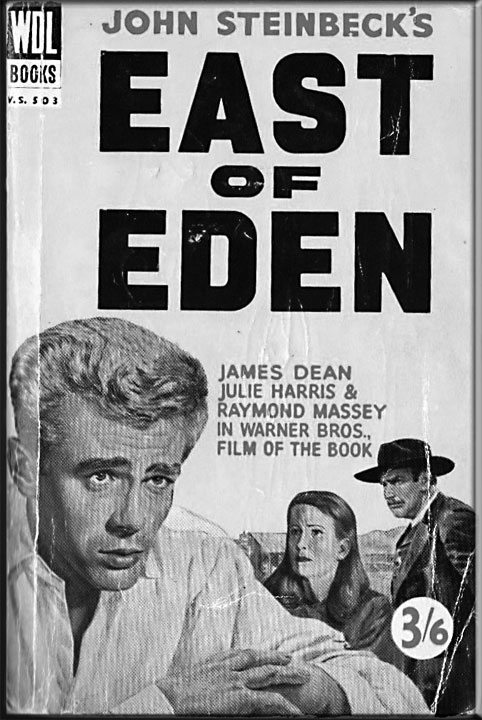

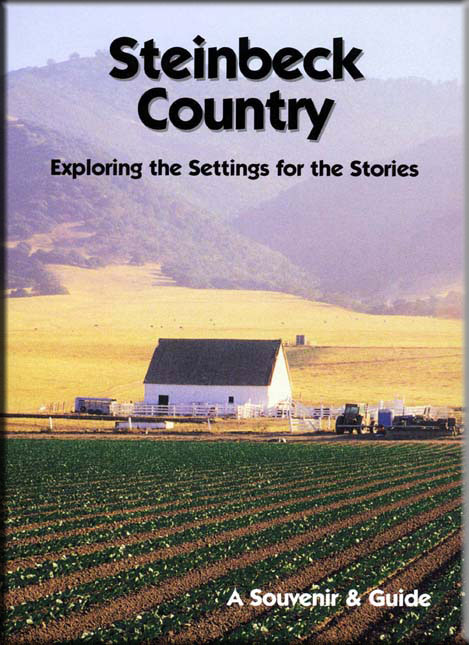

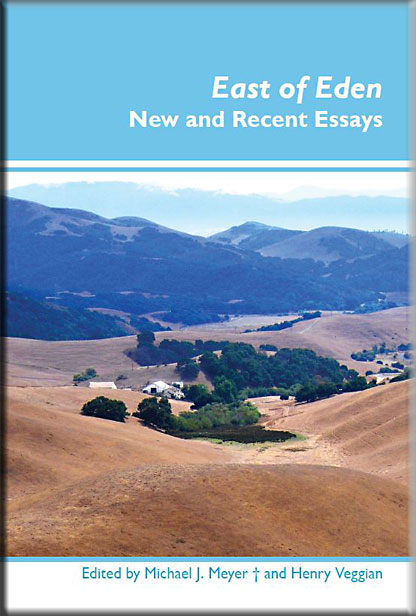

More than 60 years after it became a national bestseller, John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden remains one of the writer’s most widely read works of fiction. Set in California’s Salinas Valley, where the author grew up and is buried, East of Eden recreates a turbulent era in American life, the period from the Civil War to World War I, through two generations of a pair of Salinas Valley families whose individual lives intersect dramatically during an era characterized by change and conflict in the Salinas Valley and on the world stage. In describing the novel’s setting as “the valley of the world,” John Steinbeck clearly meant East of Eden to be read as allegory, like the Old Testament story mirrored in its title, and as autobiography—intended, he said, for his two young sons, growing up far from the Salinas Valley after World War II. In 2010, the Steinbeck scholar Michael J. Meyer asked David A. Laws, a gifted photographer known for his bright images of John Steinbeck’s Salinas Valley, to take a series of photos to illustrate a book of literary essays on East of Eden. Meyer died in 2011, but the process of collecting and editing essays by various scholars of John Steinbeck was picked up and completed by Henry Veggian, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The result was East of Eden: New and Recent Essays, published by Editions Rodopi (now Brill) in 2013 and reviewed here.—Ed.

Images of the Salinas Valley Inspired by East of Eden

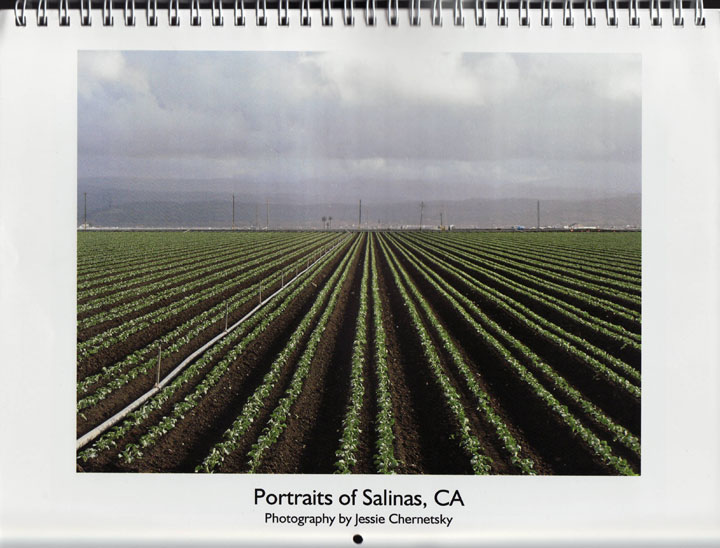

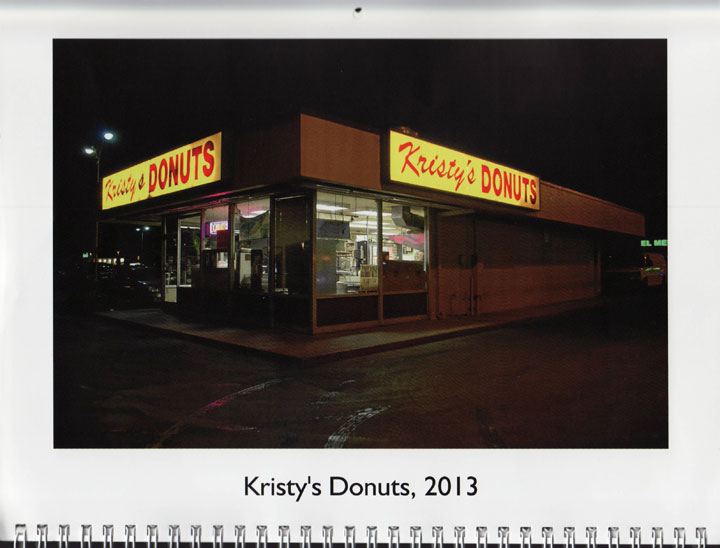

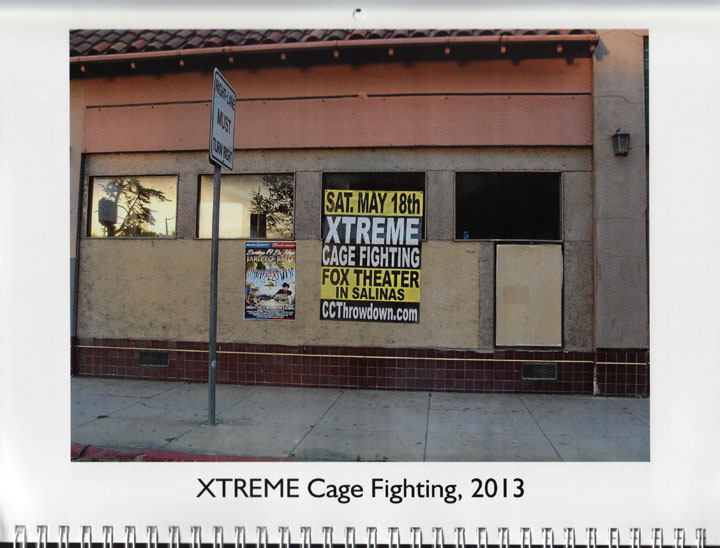

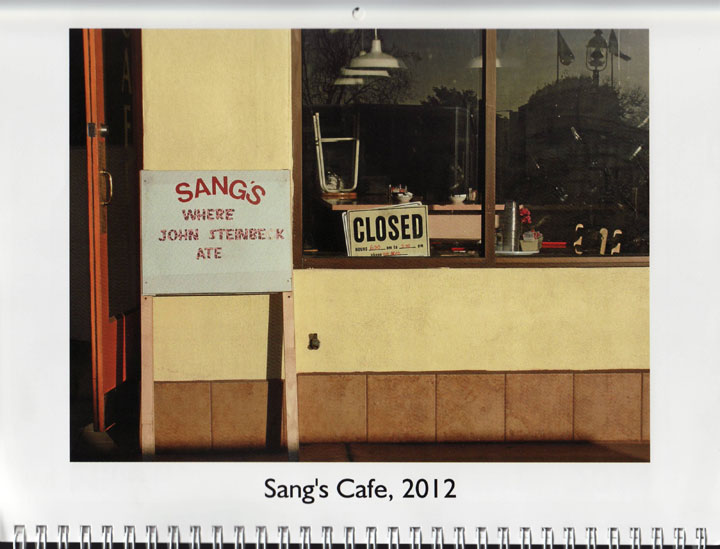

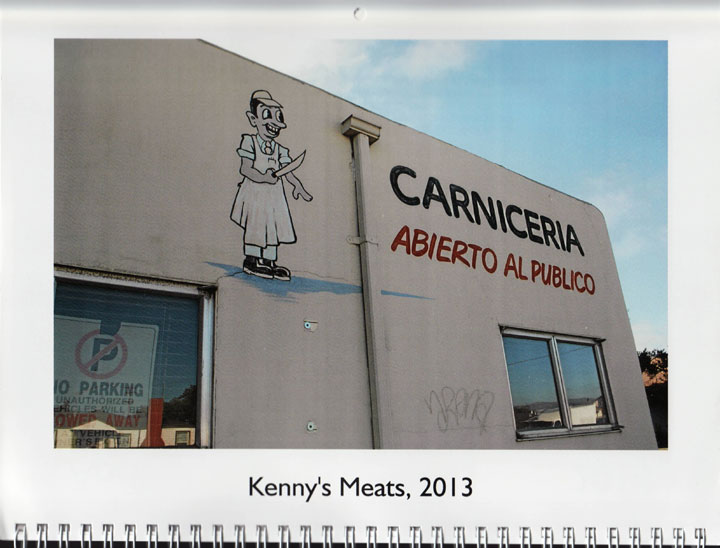

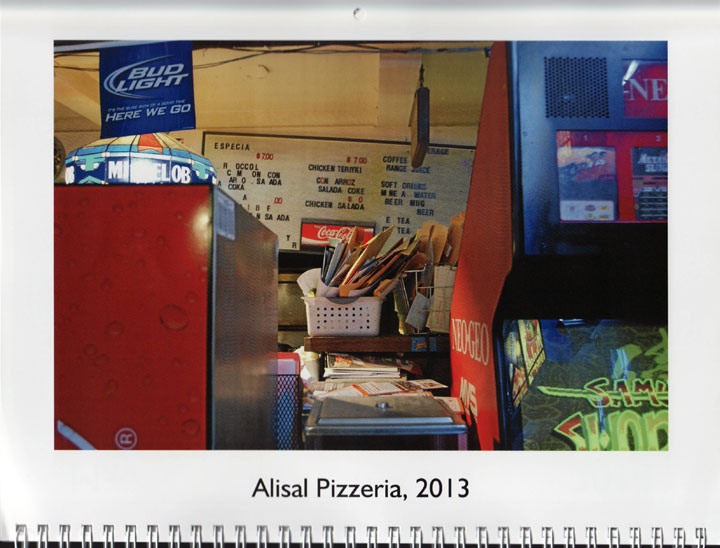

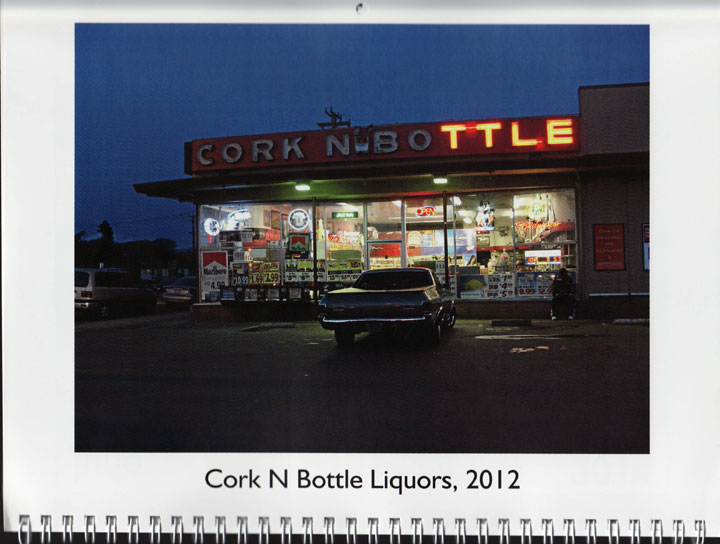

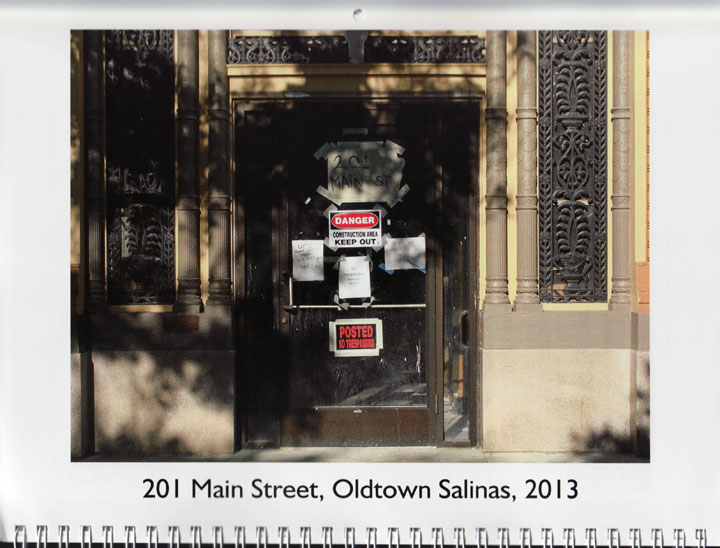

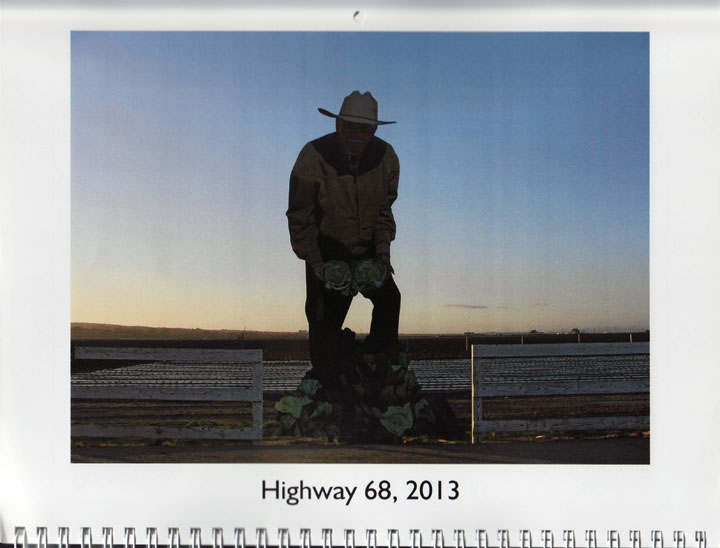

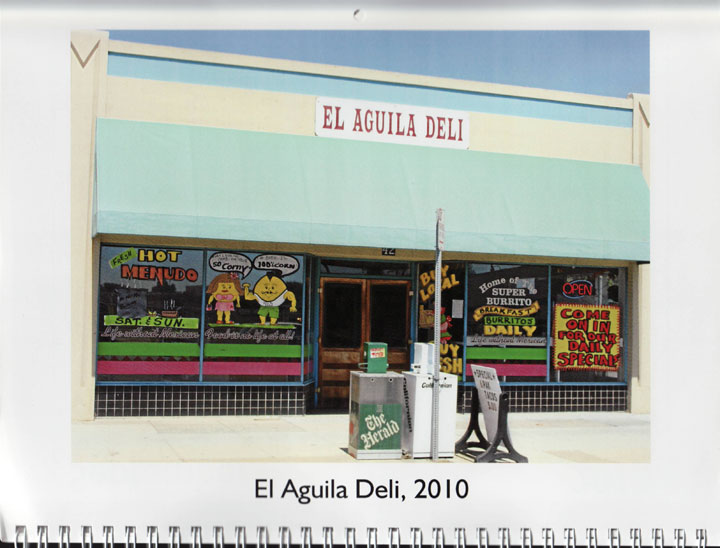

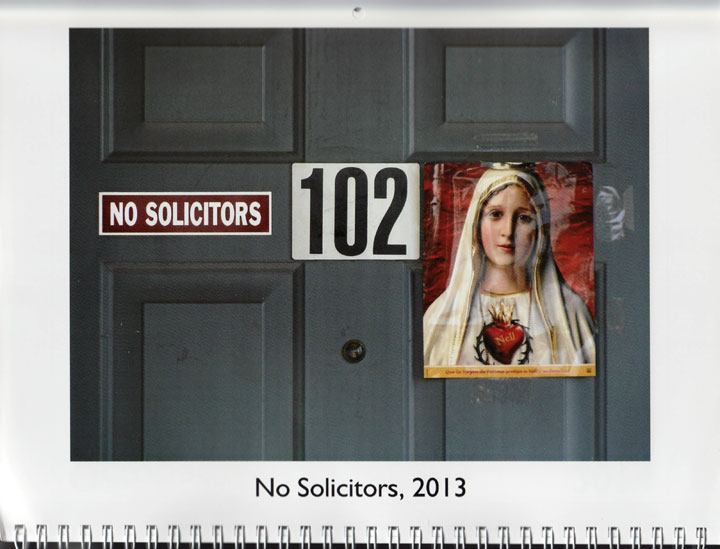

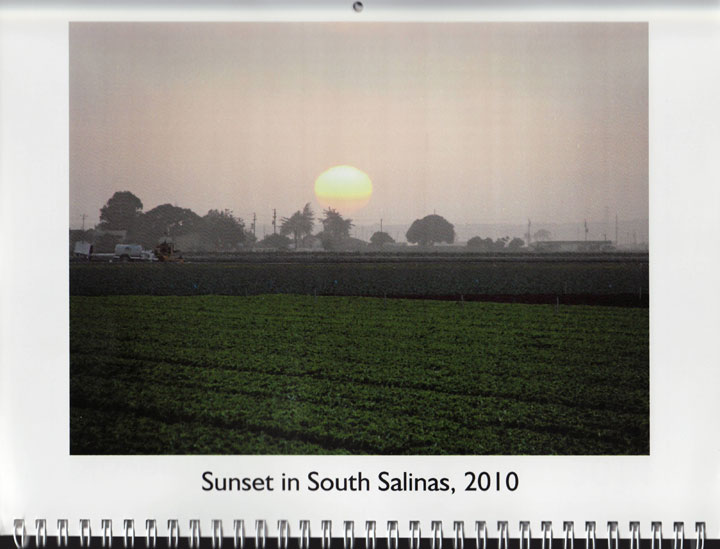

My contribution to East of Eden: New and Recent Essays appeared as a black-and-white photo essay—“Literary Landmarks of East of Eden”—comprised of 15 images that I look of locations around the Salinas Valley inspired by passages from John Steinbeck’s epic novel. The text I wrote remains the copyright of Rodopi, but I retained ownership of the following images, published here for the first time from my original color files. Although much has changed since John Steinbeck returned to his hometown in the early 1950s to recall the “sights and sounds, smells and colors” of the Salinas Valley that fill East of Eden, and even more since Adam Trask arrived in search of his own Eden, these images are recent examples of the scenes and settings that informed the author and that continue to convey the essence of those times. Page references quoting the novel are from the edition of East of Eden published by Penguin Books in 2002, John Steinbeck’s centennial.—David A. Laws

“I would like to write the story of this whole valley, of all the little towns and all the farms and ranches in the wilder hills.”—Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck and Robert Wallsten (Penguin Books, 1976), p. 73

“The river mouth at Moss Landing was centuries ago the entrance to this long inland water.”—East of Eden, p. 4

“Then the hard, dry Spaniards came exploring through, greedy and realistic. . . . Of course they were religious people, and the men who could read and write, who kept the records and drew the maps, were the tough untiring priests who traveled with the soldiers.”—East of Eden, p. 6

“There were no springs, and the crust of topsoil was so thin that the flinty bones stuck through. Even the sagebrush struggled to exist, and the oaks were dwarfed from lack of moisture.”—East of Eden, p. 9

The Plaza Hall in San Juan Bautista played the role of the King City hotel in the 1981 “East of Eden” TV mini-series.

“One morning she complained of feeling ill and stayed in her room in the King City hotel while Adam drove into the country. He returned about five in the afternoon to find her nearly dead from loss of blood.”—East of Eden, p. 133

“Later Samuel and Adam walked down the oak-shadowed road to the entrance to the draw where they could look out at the Salinas Valley.”—East of Eden, p. 293

“They left the valley road and drove into the worn and rutted hills over a set of wheel tracks gullied by the winter rains. The horses strained into their collars and the buckboard rocked and swayed. The year had not been kind to the hills, and already in June they were dry.”—East of Eden, p. 137

“’This will be a valley of great richness one day. It could feed the world, and maybe it will.’”—East of Eden, p. 145

“In the country the repository of art and science was the school, and the schoolteacher shielded and carried the torch of learning and of beauty. The schoolhouse was the meeting place for music, for debate. The polls were set in the schoolhouse for elections. Social life, whether it was the crowning of a May queen, the eulogy to a dead president, or an all-night dance, could be held nowhere else.”—East of Eden, p. 146

“’I don’t know whether you noticed, but a little farther up the valley they’re planting windbreaks of gum trees. Eucalyptus—comes from Australia. They say the gums grow ten feet a year.’”—East of Eden, p. 164

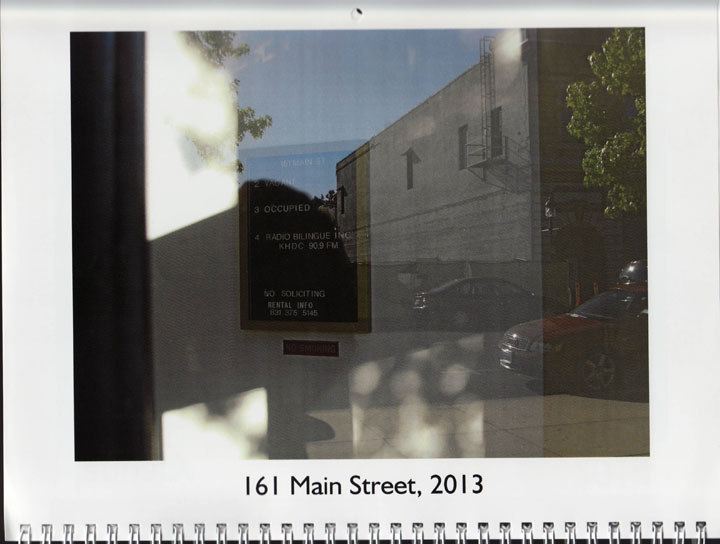

“At eight-thirty on a Wednesday morning Kate walked up Main Street, climbed the stairs of the Monterey County Bank Building, and walked along the corridor until she found the door which said, ‘Dr. Wilde—Office Hours 11-2.’”—East of Eden, pp. 240-241

“The traditional dark cypresses wept around the edge of the cemetery, and white violets ran wild in the pathways. . . . The cold wind blew over the tombstones and cried in the cypresses.”—East of Eden, p. 309

“The ‘dobe house had entered its second decay. The great sala all along the front was half plastered, the line of white halfway around and then stopping, just as the workmen had left it ten years before. . . . A smell of mildew and of wet paper was in the air.”—East of Eden, pp. 342-343

“When Adam left Kate’s place he had over two hours to wait for the train back to King City. On an impulse he turned off Main Street and walked up Central Avenue to number 130, the high white house of Ernest Steinbeck. It was an immaculate and friendly house, grand enough but not pretentious, and it sat inside its white fence, surrounded by its clipped lawn, and roses and catoneasters lapped against its white walls.”—East of Eden, p. 382

“It’s a pleasant little stream that gurgles through the Alisal against the Gabilan Mountains on the east of the Salinas Valley. The water bumbles over round stones and washes the polished roots of the trees that hold it in.”—East of Eden, p. 589