In a room on the main floor of the Steinbeck House in Salinas, California—formerly John Steinbeck’s bedroom, now known as the Blue Room—visitors can inspect a glass display case containing a signet ring that once belonged to the author. When I started volunteering at the Steinbeck House some years ago, I was told that he had given the ring to a girlfriend, but that no one knew her identity, or how old he was when the gift was made. People assumed that Steinbeck was still in high school at the time, that the ring was forgotten when the pair broke up, and that, decades later, the unidentified recipient—now an adult woman—must have come across it and donated it to the Steinbeck House.

Then, about a year ago, I was going through some papers that I found in the back of a file drawer when I discovered three letters written by a woman named Mary Ardath van Gorder. All were dated 1986 and addressed to the then-president of the Valley Guild, the nonprofit organization that has owned and operated the Steinbeck House since the mid-1970s. In the first letter, sent from a retirement home in La Jolla, California, Mary said that she had once been engaged to John and that she still owned the signet ring that his mother had given him before they met. Would we like to have the ring back, for display at the house where John lived until he left for Stanford in 1919?

My curiosity piqued, I found this passage about Mary Ardath in Jackson Benson’s great life of John Steinbeck. It told a remarkable story, about John’s brief romance with Mary when he was a struggling writer in New York during the winter of 1925-26:

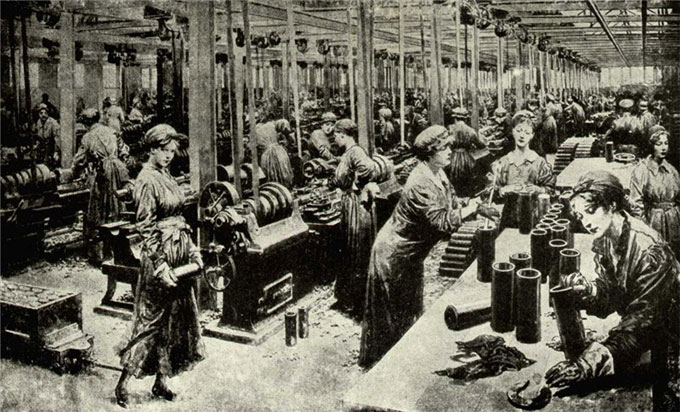

Ardath was a statuesque beauty who worked at the Greenwich Village Follies as a showgirl for a hundred dollars a week—four times what Steinbeck was making as a reporter. After meeting Steinbeck, Mary seemed to cling to him like a safe harbor. . . . Every night he waited for her outside the stage door, and nearly every night she would take him to dinner and try to talk him into getting a better job. She finally gave up on him after several weeks of trying and did marry a banker. But that is not the real ending of the story: after having settled down and had her children, she couldn’t stand it and came looking for John in California—with children in tow.

Sixty years later, now in her 80s, Mary Ardath wrote three letters that I found at the back of a filing drawer, in the house where Olive presumably gave her son the signet ring that Mary received from John in New York in 1925-26—and eventually returned to the home where the Steinbeck story started.

Readers with information about Mary Ardath’s life after the affair with John Steinbeck are encouraged to leave a comment or email williamray@steinbecknow.com—Ed.