Another Effing Dead Dog

Checking a plastic syringe, she asks again

whether I’m ready then does what she does.

She says that she could perform surgery now

then administers a second injection. I want it,

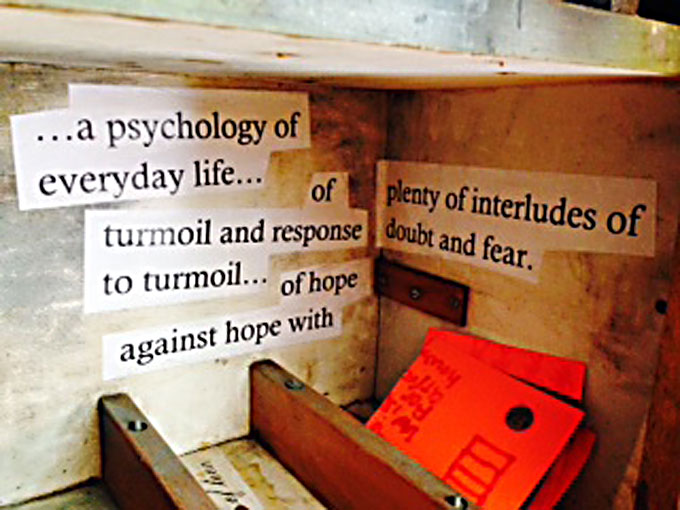

his death, to say we speak loss and that loss

is the first language in which we are fluent.

Go ahead and say it: Another effing dead dog.

But my presence in the room meant everything.

And fast forward to ashes in a Sosa cigar box,

the box traveling to Ohio to sit on a dresser.

They travel well, ashes, though the contents

are not him. The stuffed bear next to the box

is his. And I recall an aura around his gold fur

after he stopped breathing and what had to be

done had been done and I left him on a table

to be handled with reverence, it being Iowa.