Mark

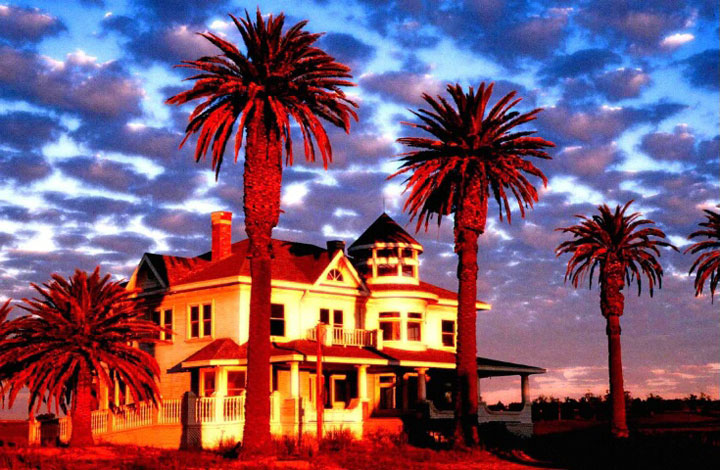

Silhouetted by a sun about to fail,

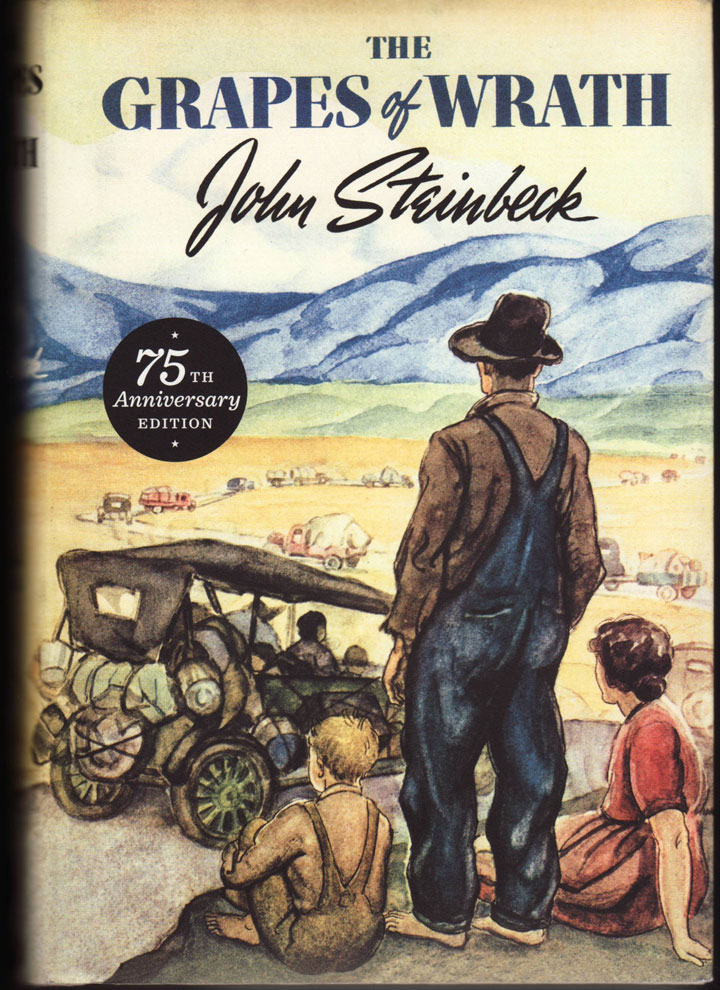

this man takes aim. On the other side

his face must gleam, as a cartridge

case, ejected, tumbles wingless.

Skyward. Into clouds. Gray eyes

focus from the shade of a wide brim.

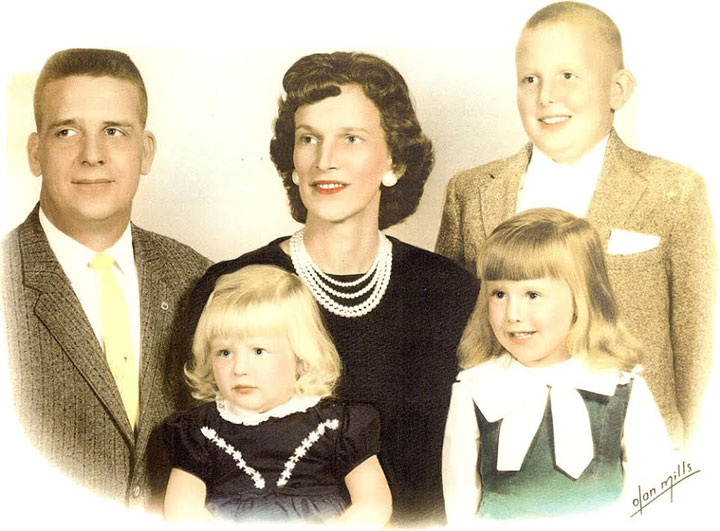

Sweat-curled hair spills from the hat

back, down his neck and collar.

The rifle butt narrows to its dark

barrel as a fist to an eager finger.

Clouds explode. Birds scatter.

His target convulses. Spins away.

In his holster a pistol sits snug,

walnut grip and trigger ready

for the short shot. To make sure,

he’ll cock again. Fire. And again.

At first, only the moon’s flushed

face begins to fade. An eye

rising into less light. Then

the red mist sudden, and fine.