“All good writing is swimming under water

and holding your breath.”

—F. Scott Fitzgerald

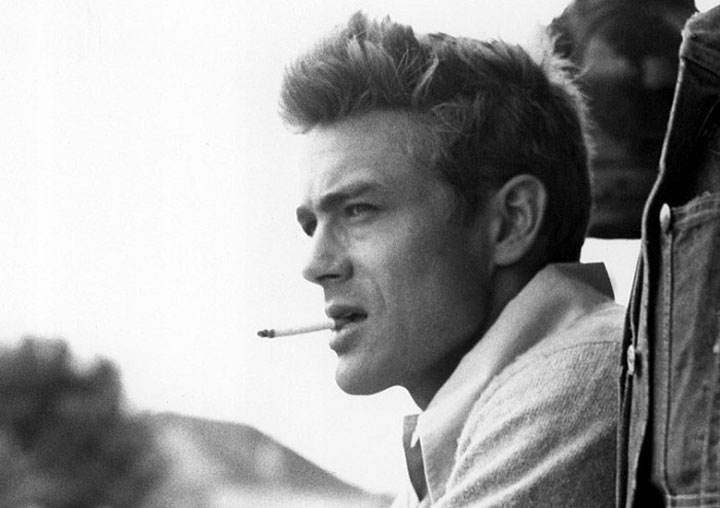

In the photograph, Zelda wears a fur and hat.

Scott has on a top coat and gloves. It’s winter.

He said Zelda had “an eternally kissable mouth.”

Said that he loved stories of her in Montgomery.

He’d begin: Montgomery had telephones in 1910.

It’s April. A warm day. Magnolias are blooming.

Zelda—ten years old—has rung up the operator

to dispatch the fire department. She climbs out

onto a roof to wait rescue. Lots of white blossoms

are falling on small shoulders. Landing in her hair.

She’s sitting, smoothing her dress when they come.

Whatever else, they looked swell in photographs.

He’d say, Zelda drew flyers from Camp Sheridan

who did figure-eights over her Montgomery home.

They crashed their biplanes trying to impress her.

What he would never say: Then she married me.

As if what happened to her later was his fault

or a series of regrets for which he was to blame.

In 1921, each existed to watch the other move—

This Side of Paradise was a hit, he was soaring.

Zelda wanted to soar herself. Float like a ballerina.

At the end of the day she wanted what she wanted:

a ticket out of Alabama. Excitement. Breathlessness.

After her third breakdown, the years in sanitariums,

visitors whispered, She was a beauty once. Trapped

at last in a burning asylum, the fire real, Zelda Sayre

Fitzgerald died locked in. Screaming to be rescued.

He would’ve been dead, buried, for years by then.