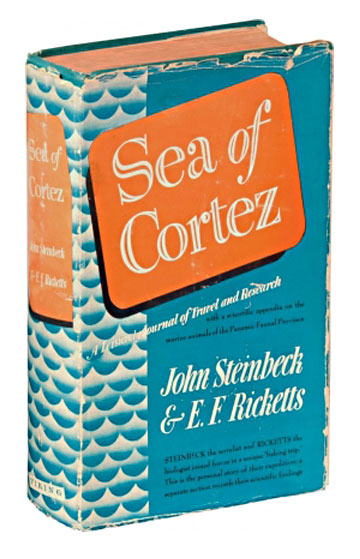

John Steinbeck’s wrote The Moon Is Down to inform Americans and inspire people in the formerly free countries of Europe—Norway, Denmark, Holland, France—occupied by Hitler’s forces in 1941. A March 1, 2022 op-ed in The Washington Post, by a literary-minded diplomat named Charles Edel, uses Steinbeck’s 1942 novella-play to educate another generation, and inspire resistance to another invasion and another dictator, eight decades later. “President Zelensky’s leadership of Ukraine’s resistance is a testament to democracy” profiles the Ukrainian president as a modern-day Mayor Orden, the fictional character Steinbeck likely modeled on the exiled mayor of Narvik, Norway. The op-ed’s subtitle—“How John Steinbeck’s ‘The Moon Is Down’ inspired resistance to occupation”—might give away the lede. But it will please fans of Steinbeck’s writing, which also includes A Russian Journal, Steinbeck’s 1948 nonfiction work in which Ukrainians emerge as victims of central planning and Russian belligerence. But that’s a subject for another op-ed on John Steinbeck’s continuing relevance.

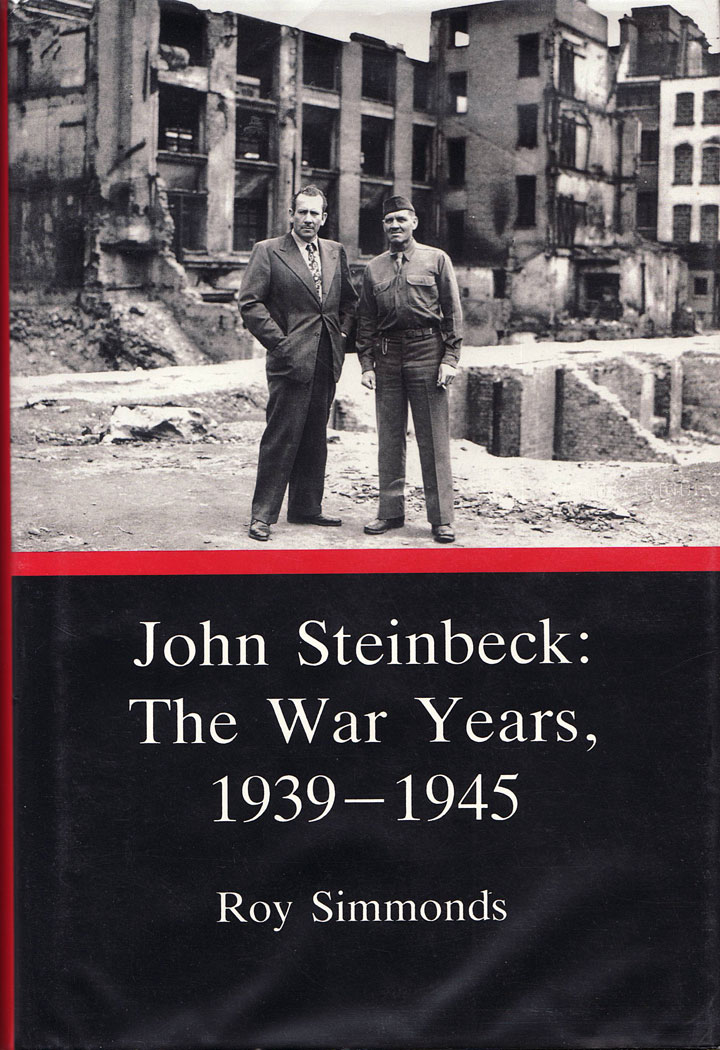

Photo of Theodor Broch, the exiled mayor of Narvik, Norway.